Watch Arwa Damon’s documentary, “ISIS in Iraq,” this weekend on CNNI at 01.30 ET and 14.30 ET Saturday, and 08.30 ET Sunday.

Story highlights

Once a successful businessman, Abdullah Shrem now works to rescue fellow Yazidis from ISIS

His network of smugglers risk their lives to bring captives out of ISIS territory

Those who have escaped say they were used as sex slaves and bomb makers

The bidding opens at $9,000. For sale? A Yazidi girl.

She is said to be beautiful, hardworking, and a virgin. She’s also just 11 years old.

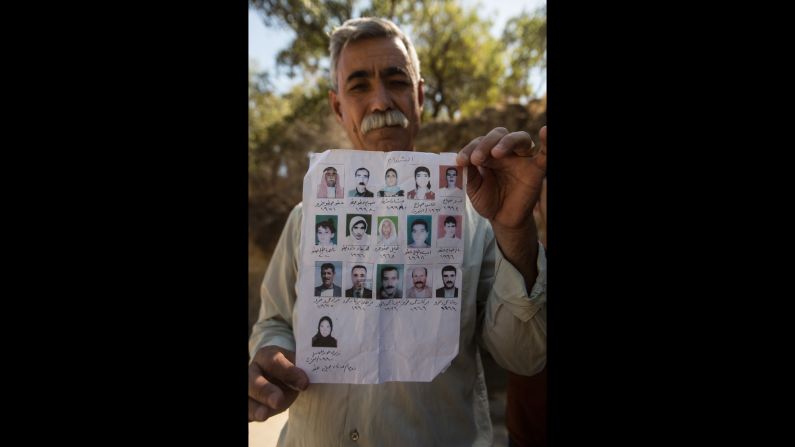

This advertisement – a screengrab from an online marketplace used by ISIS fighters to barter for sex slaves – is one of many Abdullah Shrem keeps in his phone.

Each offers vital clues – photographs, locations – that he hopes will help him save Yazidi girls and young women like this girl from the militants holding them captive.

Shrem was a successful businessman with trade connections to Aleppo in Syria when ISIS came and kidnapped more than 50 members of his family from Iraq’s Sinjar province, a handful of the thousands of Yazidis seized there in 2014.

Tens of thousands of Yazidis fled their homes and clambered up Mount Sinjar in an attempt to escape the fighters; hundreds were massacred, while thousands of women and girls were abducted and sold into slavery.

Sold into sex slavery

Desperate – and angered at what he saw as a lack of support from the international community – he began plotting to save them himself, recruiting cigarette smugglers used to sneaking illicit produce in and out of ISIS territory to help his efforts.

“No government or experts trained us,” he explains when we meet in the Kurdish region of northern Iraq. “We learned by just doing it, over the last year and a half, we gained the experience.”

So far, he says, his network has freed 240 Yazidis; it hasn’t been easy, or cheap – he’s almost broke, having spent his savings paying smuggling fees.

For those who venture into ISIS territory, the stakes are even higher – a number of the smugglers have been captured and executed by ISIS while trying to track down Yazidi slaves.

But Shrem insists the risks are worth it: “Whenever I save someone, it gives me strength and it gives me faith to keep going until I have been able to save them all.”

In some cases, the smugglers follow clues in the adverts or other tidbits of information they’re able to gather to find the Yazidis. In others, the hostages themselves reach out and plead for help, offering key details as to their location; a province or town they’ve overheard mentioned, or a local landmark they’ve been able to spot.

Once they manage to make contact, the prisoners are told when and where to go to meet the smugglers who wait for them in a nearby car. Depending on the circumstances of the rescue, it can take days or even weeks to get safely out of ISIS territory, switching from vehicle to vehicle, and waiting in safe houses.

Children as bomb-makers

Dileen (not her real name) is one of those rescued by Shrem and his team of smugglers.

She was separated from her husband when ISIS militants overran Sinjar province. The last time she saw him he was being marched away, hands up, with the other men from their village.

She and her children were taken to Mosul with the women and girls. “They separated the ones who were really pretty, and made us remove our headscarves to see the prettiest ones,” she says.

They were moved from place to place within ISIS territory: Mosul, Tal Afar, Raqqa, and finally to Tishrin, where, she says, she was sold to an ISIS fighter, who raped her repeatedly.

“They forced me, and they threatened my children,” she says, recalling the five months she spent trapped in his home.

ISIS claims the Quran justifies taking non-Muslim women and girls captive, and permits their rape – a claim vociferously denied by Islamic scholars.

While Dileen was used as a sex slave, her daughter Aisha (not her real name), who is just seven years old, was forced to work late into the night, in the basement of their apartment building, assembling IEDs for ISIS.

“I used to make bombs,” says Aisha, quietly, playing with her hair. “There was a girl my age and her mother. They threatened to kill [the girl] if I wouldn’t go and work with them,” she told CNN.

“They would dress us in all black and there was a yellow material and sugar and a powder, and we would weigh them on a scale and then we would heat them and pack the artillery.”

An ISIS militant, she says, would then add the detonation wires.

Escapees ‘can’t forget’

Fleeing ISIS: Yazidis seek safety in Shariya refugee camp

Dileen was terrified Aisha would be blown up, or that – if the family was still being held captive by her next birthday – she too would be sold as a sex slave. So when the ISIS fighter she now belonged to left to go on a military operation, she spotted a chance to escape. She called Shrem and asked him to help them flee.

“We got to a phone with the help of another woman; we got in touch with Abdullah.”

Shrem’s phone number – memorized by his relatives before their phones were confiscated by ISIS – has been passed around among captured Yazidis, who know he will help them if he can.

“I begged him to hurry up and get us before my daughter turned eight, because they would take her.”

Shrem told her to meet someone from his network at a nearby mosque the following day, then spirited her and her children out of ISIS territory.

A year on from their rescue, Dileen – now living in a refugee camp in Iraqi Kurdistan – says she is still haunted by what they went through: “I can’t forget what happened.”

Her husband is still missing, feared dead, but Dileen insists that “for my children, I have to survive.”

Plea for international action

Agony of the Yazidis

Shrem’s own sister is another of those victims, who managed to get in touch with him from behind enemy lines.

“For eight months, I didn’t hear anything from her,” he recalls. “Then she called me from Anbar.

“There was a wife of an ISIS fighter who gave her a phone and said, ‘Maybe you will be able to save yourself.’”

She was able to give him a vague description of her surroundings; eventually he was able to pinpoint her location and get a message to her.

He saved her and her youngest son, five-year-old Saif, but so far hasn’t been able to trace her two eldest sons, who were sent to ISIS training camps, or her 13-year-old daughter, who was taken away to be sold.

Thousands of Yazidis remain trapped inside ISIS territory, and Shrem fears time may be running out to save many of them from radicalization. He is calling on the international community to take action.

“If it was 50 and not 5,000 Europeans that were being raped every day by ISIS, would Europe stay silent? Of course not. There would be operations … everything would be done to save them.

“But 5,000 Yazidis being raped, the children trained and turned into walking bombs, and no one does anything. We are abandoned.”

Brainwashed by ISIS

Months on from his rescue, Saif still shows the after-effects of months of ISIS brainwashing.

“When Saif first got out, he was like a wild thing,” Shrem recalls. “We couldn’t really talk to him. He was still applying the ISIS mentality – that everyone is the enemy.

“The ISIS fighters would take him to Sharia school … they would teach him that jihad was the best thing in life.”

When Shrem asks what he’d rather play with, a ball or a gun, he doesn’t hesitate: “A gun,” he insists.

“They put this in their heads,” Shrem says, sadly. “That there is nothing better than a gun.”

Trained to kill ‘infidels’

The ISIS terror threat

Fellow ISIS captive Dilshad, aged 10, underwent the same brainwashing. His mother Samira (not her real name) says he was being groomed to be an ISIS executioner.

While his mother and siblings were held captive, he was taken to an ISIS training camp.

“They said, ‘We are going to the camp to train to fight with the Islamic state,’ [there were] little and big children [there],” Dilshad explains.

“We were running and we read the Fatiha [the first chapter of the Quran] and they wouldn’t let us drink water. They said it was so you can be trained.”

Samira was horrified when she overheard the family’s captors talking about the promise Dilshad showed. Weeks later, they were sold to another militant. It was Dilshad he wanted.

“[He] was a butcher, he would kill people, he would slaughter them,” Dilshad remembers. “He said, ‘now you kill them with a pistol,’ but I said ‘I can’t kill.’

“He said ‘OK, next time you will kill them.’ I said ‘Why are you killing people in front of me?’ He said ‘So you learn.’ He killed people with a sword… he said they are infidels.

“The first time I saw them kill in front of me I was very scared, but then I wasn’t as scared as the first time.”

Dilshad says the ISIS militant told him he was like a son, and urged him to kill members of his real family: “They said to me, ‘your father is an infidel, if you see him kill him.’”

Radicalized teens ‘nuclear bombs’

Samira says that, over time, her son grew attached to the executioner.

“My son didn’t threaten us, but he asked me ‘What would you think if I kill?’ I burst into tears. I said ‘How can you kill innocents?’

“I couldn’t stop crying; he hugged me and said ‘I won’t kill anyone, I will listen to you.”

After more than a year in captivity, Samira and her family were rescued before ISIS militants could turn Dilshad into a killer.

Saif and Dilshad are the lucky ones – they are safely out of ISIS hands – but many others, including Saif’s brothers, remain inside their territory.

Every family has someone who is missing, presumed dead, and there is little or no psychological support for those who have managed to get out.

“What I am most worried about are those who finished the Sharia [school] and the training, they are fully brainwashed,” says Shrem.

“I consider each of them to be a nuclear bomb that will come and target the Yazidis.”

CNN’s Brice Laine contributed to this article.