Last week a group of 17 American news organisations, including the New York Times and Washington Post, served a cease-and-desist legal order against a start-up news platform. The platform, called Brave, was launched in January by the creator of JavaScript, Brendan Eich. The Brave browser had been created in part in response to two recent trends in news delivery: the emergence of mobile platforms such as Apple News and Facebook’s Instant Articles, and the growing use of software that allows readers to block advertisements from news content.

Eich’s model had ad-blocking software built in – but its new trick was to strip out ads sold with news content and replace them with ads of its own. This practice served, Eich argued, to enable quicker loading of news pages, and to “protect the data sovereignty and anonymity” of users. Unlike on Facebook, say, no data trail would be left by those who clicked on the items. Moreover, Brave would offer 55-70% of ad revenue directly back to the original publisher.

The movers of the lawsuit, those original publishers, were not persuaded. The cease-and-desist notice sent to Eich branded his business model “blatantly illegal” and alleged that Brave was profiting from the “$5bn” a year the newspaper industry invested in original journalism. Their letter suggested Brave was simply stealing their articles and pasting them on its own website for profit.

On one level that argument stood up to scrutiny. On another, however, Brave seemed a very curious target for the newspapers’ collective litigious outrage. Much of the news content appropriated by Brave is also shared and available on platforms such as Apple News and Instant Articles, where the share of revenue generated is a fraction of that offered by Eich’s start-up, a return that diminishes to next to nothing when allied with pervasive ad-blocking software. Eich’s response to the lawsuit reflected his surprise: “Brave is the solution,” he argued, “not the enemy.” He certainly seemed to have a point.

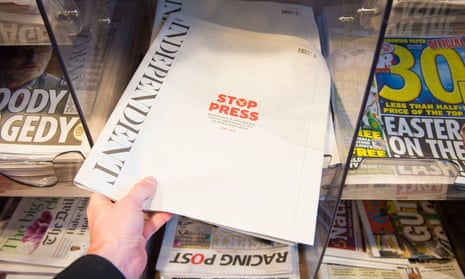

Perhaps the lawsuit offered a vision of an industry finally at the end of its rope. That journalism faces an uncertain future is certainly not news. About 15 years ago, when digital media became a reality, news organisations tended to adopt one of two tried-and-trusted crisis-management strategies: ostrich or lemming. They either tried to ignore the new landscape, sticking stubbornly to what they knew, preparing stout paywall defences around their journalism, or they leapt headlong into the thin air of the digital future, trusting in the sustaining miracle of unknown new revenue streams before they hit the rocks. Among those news publishers to have survived the first couple of waves of that revolution – and plenty have not – neither strategy could be claimed a wholehearted success.

As the past couple of weeks’ revelations from Panama have emphasised, the painstaking, mischief-making work of newsrooms is still our best hope for shedding light on the shadiest corners of the world, a role amplified by a global readership, big data and an increasingly interconnected media. But while the appetite for news and all the opinion and analysis that depend upon it has never been keener (or more necessary), the desire among readers to pay directly for that “content” online maintains a largely downward curve. Print circulation in Britain in the past decade has fallen predictably sharply across the board and revenue from the shift online has in most cases not begun to compensate. In America, journalist was named the fourth most endangered job in 2015, nestled between farmer and logging worker. And it’s not only the newspaper-based providers of news that have been feeling these ill winds. This week the FT reported that Buzzfeed was slashing its 2016 projections in half to $250m. Then Buzzfeed itself reported on the “digital media bloodbath” detailing job losses at Mashable, the International Business Times, Gigaom, Al-Jazeera America and the publishers of the Observer, the Guardian Media Group.

Though there are notable pockets of resistance, that broad contraction shows no sign of slowing. Some of the more messianic commentators on the digital future were prone, in the beginning, to make predictions about the great shift in reading and buying (or not buying) habits leading to a golden age of investigation and reporting. Two prophecies were particularly persistent: that a brave and brilliant new democracy of citizen journalists and bloggers would triumphantly evolve to replace the handful of “gatekeepers” of information; and only newspapers that embraced digital fully, that first jumped off the cliff, would be raised up for their faith in free content by the inevitable migration of advertising revenue from print to digital.

For a fingers-crossed period both those predictions seemed just about plausible. The emergence of social media and the growing dominance of mobile phones as the primary conduit for news and information has sharply undermined both elements of that optimistic future, however. The ubiquitous quick fixes of social media rendered the kind of in-depth blogging that prophets of citizen journalism had in mind almost immediately obsolete, beyond diehards and obsessives: who wanted to write 1,400 unpaid and unread words when a sly 140 characters would do?

And while the exponential growth of online readership attracted a rising proportion of advertising revenue, it did not begin to replace the hole in newspaper finances left by the collapse of print – and particularly classified – advertising. The emergence of ad-blocking software that strips online content of the lifeblood of its paid-for messages has abruptly stalled that growth. The software was estimated to have cost publishers $22bn worldwide in lost revenue last year. That beguiling mantra of “monetised content” – a phrase never knowingly underused in newspaper offices, seems an ever more mythical concept.

In a recent lecture at Cambridge University, Emily Bell, formerly business editor of the Observer and digital editor of the Guardian and now director of the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia Journalism School, New York, summed up this new world order in stark terms. The lecture was titled “The End of the News As We Know It: How Facebook Swallowed Journalism”. In it Bell argued that what has happened to journalism in the past five years through the impact of social media has been at least as radical an upheaval as what occurred in the previous 10, when the arrival of the web looked for all the world like a once-in-millennium, Gutenberg-scale change.

The current sudden transition in how people access news on mobile alters all that has gone before. “The ‘four horsemen of the apocalypse’, Google, Facebook, Apple and Amazon,” Bell suggested, are presently “engaged in a prolonged and torrid war over whose technologies, platforms and even ideologies will win. It is as fierce as newspaper rivalries in the 60s and network television in the 70s, but with much more at stake.”

In some respects in the past year, Bell argued, “legacy publishers” (dread phrase) have unexpectedly, and probably temporarily, “found themselves the beneficiaries of this conflict”. The emergence of third-party mobile platforms to deliver news, such as Discover on the photo-messaging app Snapchat, Instant Articles on Facebook, Apple News on iPhone and Accelerated Mobile Pages (AMP) on Google has seen the horsemen unexpectedly dismounting to parley with some of those publishers threatened by apocalypse. In different ways the new apps and platforms offer readers fast access to newspaper and magazine content fed directly to them. For traditional “content providers”, or journalists, such platforms increase readership (good news), but by cutting the direct link between publishers and readers, they also diminish the possibilities of revenue through advertising (bad news).

While Google and Facebook continue to accumulate and monetise information about their users post-by-post and click-by-click, newspapers, having “outsourced” their content, get to know next to nothing useful (or saleable) about their readers. Further, at the same time as Apple announced Apple News, it also allowed ad-blocking software to be downloaded from its app store, at a stroke potentially closing down the possibilities of advertising to anyone reading news on an iPhone.

Bell suggested this had left commercial news organisations with three choices. Rock, hard place and even harder place. One is to “push even more of your journalism straight to an app like Facebook and its Instant Articles, where ad-blocking is not impossible but harder”. A second is to accept that chasing online traffic through such platforms is “not only not helping you, but is actively damaging your journalism, so move to a measurement of engagement rather than scale”. The Guardian’s membership scheme, or more traditional subscription models, would be examples of this. Or three, rely on revenue from ads that don’t look like ads – “native advertising” – which no longer recognise the once sacred and impermeable wall between editorial content and paid-for messaging – and which already fuels the growth of companies like BuzzFeed.

The risk of trying to compete head-on with the ubiquitous social platforms by refusing to feed content looks reckless. But, as Bell observes, collaboration, the current general direction of travel, presents all kinds of different risks: “You lose control over your relationship with your readers and viewers, your revenue, and even the path your stories take to reach their destination.” Having failed or felt powerless to force any of these questions with the tech giants, it seems that last week American newspapers plucked up the courage to draw a belated line in the sand by suing Brave.

That suit also raises another question. Where might news go next? The one option that Bell’s analysis does not countenance in this new world order is the wildly old-fashioned possibility of people paying directly for the things that they like reading. The idea of micro-payments for journalism has been mooted for as long as digital media has existed, and largely rejected as unworkable or unacceptable to the new generation of readers. In response to the emerging mobile landscape, however, a few innovators are exploring whether the concept can be revived. As a journalist, it can be tempting to see them as the cavalry.

Alexander Klöpping set up Blendle in Holland in 2014. The site originally handpicked the best articles from a range of newspapers and magazines and sold them on an individual basis to those who had signed up to the site and set up an account. Payment, established by the original publisher of the content, ranged from about 5p to 20p for the longest features; 30% of the revenue went to Blendle, the rest to the publisher. Payment was automatically taken from the reader’s account, but if, having reached the end of a story, the reader felt short-changed an immediate refund could be claimed. On this basis Blendle has established 500,000 regular users in Holland and Germany. The beauty of the site is that rather than negotiating subscriptions and paywalls and memberships from a variety of favourite publications, readers get one-click access to a version of all of them tailored to their tastes. Two weeks ago, with backing from the New York Times and the German media giant Axel Springer, Klöpping launched his site in the United States, with content from a range of papers and magazines including the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and many others. In the first 10 days 10,000 readers signed up to the beta version, beating expectations, Klöpping told me by phone last week. These are small numbers in the context of Facebook, for example, but they are a start.

Klöpping’s “crazy idea” relies on a couple of hunches. The first is that “the platforms that the big tech companies have come up with … in the end the only measure of quality they have is the number of eyeballs, and I don’t think that is the measure of great journalism.”

The other is the example of the music and film industries. More than half of Blendle’s users share Klöpping’s own profile: under 30, highly educated, the first generation to grow up with free content. “I never paid for music in my life before iTunes and Spotify came along,” Klöpping says. “I would just download everything from Napster like everyone else. The same was true with movies, but all of a sudden my friends are paying for Netflix and they are paying for Spotify.”

They do so, he believes, not out of any pang of conscience, but because those sites elegantly created a one-stop destination. “Getting everything on one platform, plus making it easy to search, plus having your friends all there and seeing what they are listening to, plus having a little bit of your own space where you can create playlists. All of these things together are apparently enough to get people to spend 10 bucks a month.” What worked for music, he believes, can work for journalism.

A few other start-ups share that faith. Among the most interesting is a prototype website and app called Lumi news. It has been created by Martin Stiksel and Felix Miller, based in east London, who made a small fortune as creators of the music recommendation site Last.fm and are now turning their algorithms towards news. Their secret sauce, Miller suggests, is that they have “been in this space for 15 years now. We think we know how machine learning can translate into entertainment and information.”

Their particular watchword is personalisation. “We really excel in utilising the data store that the user has lying around like garbage,” Miller says.

Having used their website for a couple of days, it seems they might be on to something. Certainly the automatic tailoring of content to my interests seems quite precise. “What we are doing is using the same kind of technology that advertisers use, but employing it for content discovery rather than trying to sell you something,” Stiksel says. They believe that the way to compete with the tech giants is for providers to “customise, customise, customise”. They seem slightly surprised that newspaper sites and apps have never pursued this strategy with any real intent. The Lumi duo won’t yet disclose how they plan to make money from their efforts, though they find the Blendle model fascinating. “We are in the game of going with what works,” they say (along with everyone else).

What works on Blendle itself is somewhat counter-intuitive. Klöpping finds that in our attention-deficit times there is a growing market for reading things at length. “The stories that work well on Blendle are hardly ever the ones that crop up on the most-read lists of newspapers. It is opinion pieces that have special insight, great writing, big interviews, profiles, deeply researched reporting.”

It is Klöpping’s hope that if and when people start to pay for content in significant numbers it will show that it is quality journalism that actually makes the most money. “It can be a way to move away from this terrible yearning for clicks and the simplification of content,” he says. “You look at all the articles written each day [and] so much of it is crap, but there are a few articles each day that a journalist or an editor is really proud of. Those work well on our site.”

What proportion of people ask for their money back? I ask, inevitably.

“About 10%. When a new user signs up it is higher. But after we get to understand a bit more what they want, it is less.”

The refund button asks users to give a reason for their claim. Chief among them is this one: “the article didn’t live up to or agree with the headline.” Some things never change.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion