It started with a post on social media. Or, to be more exact, a series of posts about a visit to McDonald’s to buy a milkshake. Within hours, Josh Raby’s gripping account on Twitter was international news, covered by respected outlets on both sides of the Atlantic.

“This guy’s story about trying to buy a McDonald’s milkshake turned into a bit of a mission and the internet can’t get enough of it,” read the headline on Indy100, the Independent’s sister title. The New York Daily News said he’d been “tortured”. Except, as McDonald’s pointed out – and Raby himself later admitted – the story was embellished to entertain his Twitter followers, although he says he based it on real events.

Raby’s was the latest thinly sourced story that, on closer inspection, turned out not to be as billed. The phenomenon is largely a product of the increasing pressure in newsrooms that have had their resources slashed, then been recalibrated to care more about traffic figures.

And, beyond professional journalists, there is also a “whole cottage industry of people who put out fake news”, says Brooke Binkowski, an editor at debunking website Snopes. “They profit from it quite a lot in advertising when people start sharing the stories. They are often protected because they call themselves ‘satire’ or say in tiny fine print that they are for entertainment purposes only.”

Facebook, a source of a lot of traffic from many online titles, has recognised the role it plays in driving the market, and in January 2015 promised to tweak its algorithm to demote fake news articles in users’ feeds.

Binkowski says that, during her career, she has seen a shift towards less editorial oversight in newsrooms. “Clickbait is king, so newsrooms will uncritically print some of the worst stuff out there, which lends legitimacy to – in a word – bullshit. Not all newsrooms are like this, but a lot of them are.”

The Guardian has heard numerous accounts from journalists about the pressures in UK newsrooms that lead to dodgy stories being reported uncritically, but none would go on record. One person working for a UK news publication claims the industry is now “like the wild west”. The source, who asked not to be named for fear of recriminations from her employer, says: “You have an editor breathing down your neck and you have to meet your targets.”

Asked what the driving factor was, she said: “It is a combination. There are some very young and excited journalists out there. If you do a story and it goes viral, it is very exciting. But big bosses are trying to meet targets. There are some young journalists on the market who are inexperienced and who will not do those checks.

“So much news that is reported online happens online. There is no need to get out and doorstep someone. You just sit at your desk and do it and, because it is so immediate, you are going to take that risk. Editors will say, ‘The BBC got that six seconds before we did.’”

Another journalist, who asked not to be named for similar reasons, says: “There is definitely a pressure to churn out stories, including dubious ones, in order to get clicks, because they equal money. At my former employer in particular, the pressure was on due to the limited resources. That made the environment quite horrible to work in.”

In a February 2015 report for the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia University, Craig Silverman wrote: “Journalists have always sought out emerging (and often unverified) news. They have always followed on the reports of other news organisations. But today the bar for what is worth giving attention seems to be much lower.

“Within minutes or hours, a claim can morph from a lone tweet or badly sourced report to a story repeated by dozens of news websites, generating tens of thousands of shares. Once a certain critical mass is reached, repetition has a powerful effect on belief. The rumour becomes true for readers simply by virtue of its ubiquity.” Silverman points out examples where titles – including the Guardian – reported false rumours, which had to be corrected later.

And, despite the direction that some newsrooms seem to be heading in, a critical eye is becoming more, not less crucial, according to the New York Times’ public editor, Margaret Sullivan. “Reporters and editors have to be more careful than ever before. As hoaxers get more sophisticated and more numerous, it’s extremely important to be sceptical and to use every verification method available before publication.”

Yet those working in newsrooms talk of dubious stories being tolerated because, in the words of one, some senior editors think “a click is a click, regardless of the merit of a story”. And, if the story does turn out to be false, it’s simply a chance for another bite at the cherry.

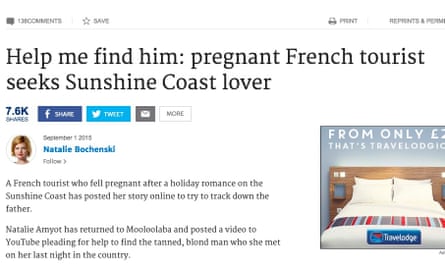

In September 2015, the Brisbane Times was one of many titles to report the story of Natalie Amyot, a French tourist who had posted a video on YouTube saying she was seeking help to find a man with whom she’d had a one-night stand after discovering that she was pregnant. The same title reported the following day that it had been a set-up.

In June 2014, Huffington Post and Mail Online were among those to report that three-year-old Victoria Wilcher, who had suffered facial scarring, had been kicked out of a KFC because she was frightening customers. Later, both the Mail and Huffington Post were among those reporting KFC’s announcement that two investigations had found no evidence to support the claims.

And, in November last year, the Independent and the BBC were among titles to pick up the story of a Vietnamese-Australian man calling himself Phuc Dat Bich, who complained he had been banned by Facebook because of his name. He would give no interviews. Months later, Indy100 – then named i100 – and the BBC were among those reporting that he had made it all up to “fool the media”.

Verification and fact-checking are regularly falling prey to the pressure to bring in the numbers, and if the only result of being caught out is another chance to bring in the clicks, that looks unlikely to change.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion