Developing the Next Generation of Enterprise Leaders

Aspiring corporate leaders first learn to build and implement visions for their individual business units. But as they advance in their careers, executives also must learn how to lead with an enterprise perspective.

Topics

Anat Gabriel is managing director and chairman of Unilever Israel, a relatively small operation that sells the usual array of Unilever products but also has two categories of its own, a breakfast cereal brand called Telma and a line of snack foods that are unavailable anywhere else. She calls them “local jewels”; they account for about a third of the Israeli unit’s business.

Unilever, the world’s second-largest consumer goods company, operates in nearly 200 countries and owns brands including Dove soap and Lipton tea.1 It expects Unilever Israel to promote the company’s global brands, but the local unit is still expected to make its numbers, which means that Gabriel must also invest in the local products such as Telma cereal. Gabriel’s team doesn’t always understand the trade-offs she has to make — decisions to support global brands inevitably take away from local initiatives. “To be successful,” she said, “I must work with my team to align our agenda locally in Israel with the broader Unilever enterprise agenda. I need to help my people see how the pieces of the puzzle fit together.”

Gabriel is a sterling example of an “enterprise leader” — an executive who is as successful at serving the needs of the enterprise as she is at growing the unit she heads — and CEOs want more leaders like her. A survey we recently conducted of top business executives from major international organizations found that 79% said it was extremely important to have leaders who act on behalf of the entire organization and not just their units.2 The rest said it was very important. And nearly 65% of those surveyed said they expected at least half of their senior and midlevel managers to behave as enterprise leaders.3

The reasons are obvious. Customers increasingly want integrated solutions instead of products,4 so different business units need to work together seamlessly. Companies are also attempting to share resources more efficiently across functional, geographic, and business unit boundaries.5 The expectation that managers will know what’s happening elsewhere in the enterprise is rising, in part because new competitors can appear out of nowhere. Ironically, few organizations have been set up to support the development of enterprise leaders. Some 70% of the top executives in our survey said they were investing little (25% or less) of their leadership development budgets and their managerial time and energy in producing the next generation of enterprise leaders.6

So how are managers learning to become effective enterprise leaders, and how can organizations encourage their development? Our initial research on the activities of enterprise leaders began almost a decade ago.7 For this article, we surveyed and conducted in-depth interviews with scores of executives from the Americas, Europe, and Asia. (See “About the Research.”) What we found was that, regardless of the business or the location, enterprise leaders developed their capabilities in similar ways — through a combination of deliberate personal development, high-level mentoring, and opportunities afforded by their work that enabled strong unit performers to become even more effective as enterprise leaders.

The Hard Work of Enterprise Leadership

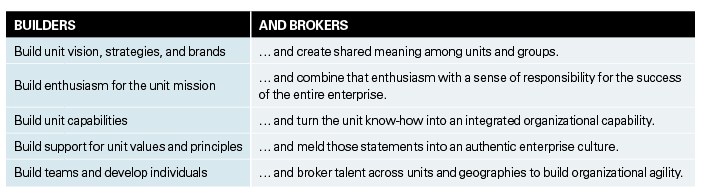

The essence of enterprise leadership lies in the need to combine two often incompatible roles — those of builder and broker. Aspiring leaders learn early on in their careers to build visions for their units, strategies to implement those visions, and teams to execute the strategies.8 But as they progress in their careers, they must begin to take on responsibility for the enterprise as a whole. We heard this time and again in our interviews. We saw it in the survey data and discussed it in our teaching sessions. We are not talking about either-or propositions: Rather, enterprise leaders must excel at being both advocacy-oriented builders and integration-minded brokers. That means they need to build their unit’s vision and integrate it into the wider corporate vision, clarifying where the enterprise is going and how their teams can best contribute, both within and beyond unit, geographic, and functional boundaries. They must build unit capabilities and share resources and business know-how across units to contribute to enterprisewide organizational capability. They need to reconcile their team’s passion for fulfilling their unit’s mission with a sense of responsibility and accountability for the success of the enterprise as a whole. (See “The Dual Roles of the Enterprise Leader.”)

The Dual Roles of the Enterprise Leader

As executives progress in their careers, they take on additional responsibility for the enterprise as a whole. They must excel as both advocacy-oriented builders and integration-minded brokers.

Michael Gladstone, regional president and U. S. country manager for innovative products of Pfizer Inc., the pharmaceuticals giant headquartered in New York City, offers a compelling example. When he learned that Pfizer’s team for marketing its blood thinner Eliquis in Japan needed additional support in optimizing the marketing plan and determining how to focus the team’s talent, Gladstone decided to shift a star member of his own team to the Japanese project, even though he had no responsibility for or direct stake in the Japanese unit’s success. What’s more, reassigning the employee in question meant that he had to revisit his plans for another initiative within his own unit. With this move, he was demonstrating an enterprise mindset — a willingness to take a hit on his short-term performance for the benefit of Pfizer as a whole.

Rod MacKenzie, Pfizer’s group senior vice president and head of PharmaTherapeutics research and development, faced similar challenges. Although he runs three areas of research, he pays attention to what’s happening across the company, recognizing that competition for resources is intense. “We want people to fight for funding, to believe that what they are working on is the most important thing happening in the company,” MacKenzie said. “But, at the same time, when it becomes clear that it is time to shut down a project in order to redirect resources to more promising therapies, I need to drive home that under those circumstances we are Pfizer first and unit second.”

At Li & Fung Limited, a leading consumer goods design, development, sourcing, and logistics company headquartered in Hong Kong, Paul Raffin, CEO and president of The Frye Company and a group president at Li & Fung, operates in a similarly nuanced environment. Li & Fung has 28,000 employees spread across some 300 offices and distribution centers in more than 40 markets. Its sourcing network encompasses more than 11,000 vendors around the world.9 At the enterprise level, Li & Fung creates efficiencies for its vast network of contract manufacturers by taking orders and buying the components (zippers, for example) from a variety of vendors.

The Frye Company, an artisanal boot and shoe manufacturer based in New York, might not seem to fit neatly into Li & Fung’s global sourcing process.10 But Raffin’s responsibility is to make sure that Frye can thrive in a competitive market where direct online selling is the norm. “Designers put their heart and soul into creating beautiful products that are then subjected to the ‘commercialization’ process, which, if not properly managed, can significantly alter the product’s aesthetic,” said Raffin, adding that rewarding cross-functional teams with performance bonuses greatly aids in the company’s ability to promote both the “need to understand” and the “need to feel understood.”

Balancing the goals of the unit with the broader interests of the enterprise can be difficult. “Let’s face it — it’s easier to be a silo leader,” Unilever’s Gabriel said. “This is a more complex leadership challenge, it takes more energy, and it is simply harder to do.” For her, advocacy-oriented building was essentially table stakes, while the more integrative brokering role became key to her ability to be an effective enterprise leader. The central challenge was to reconcile a series of embedded tensions and paradoxes, many of which seem to be unresolvable.11

And yet when we asked company leaders and HR professionals about the obstacles to developing enterprise leaders, they focused not on the challenges of the job itself but on organizational barriers. Most often they cited strong organizational cultures that praised builders and rainmakers, and reward systems that reinforced a silo-performance-first mentality and entrenched habits. Most people came up the ranks in silos, so they didn’t feel the impetus to change; the assumption was that if you hit your numbers you would be left alone.

What this told us was that organizations were set up to develop strong building skills — and not the brokering skills so many of the top leaders we talked to told us they needed. Despite the fact that so few resources were devoted to deliberately developing enterprise leaders, top executives said they wanted their high-potential leaders to start exhibiting these behaviors early in their careers, even if they weren’t yet in a position to influence activity outside of their area. Pfizer’s Gladstone suggested that the earlier one can plant the seeds of an enterprise mindset, the better. “Even if people do not ultimately become senior leaders, it’s helpful for them to think broadly,” he noted. “Every colleague in the organization, no matter how narrowly focused their role, should be thinking about the enterprise and how what they are doing is ultimately helping the patients that we serve.”

How, then, did these enterprise leaders actually learn how to be both builders and brokers? In short, with difficulty.

The Enterprise Leader’s Mindset

“A lot of leaders don’t stick around long enough to learn how to become artful brokers,” observed Pfizer’s MacKenzie. “They do the building, enhance their personal brands, and then move on. Brokering takes more time to learn. It’s a matter of developing a mindset, really — a way of thinking about the world around you. You won’t find these lessons in any training program in a course catalogue.”

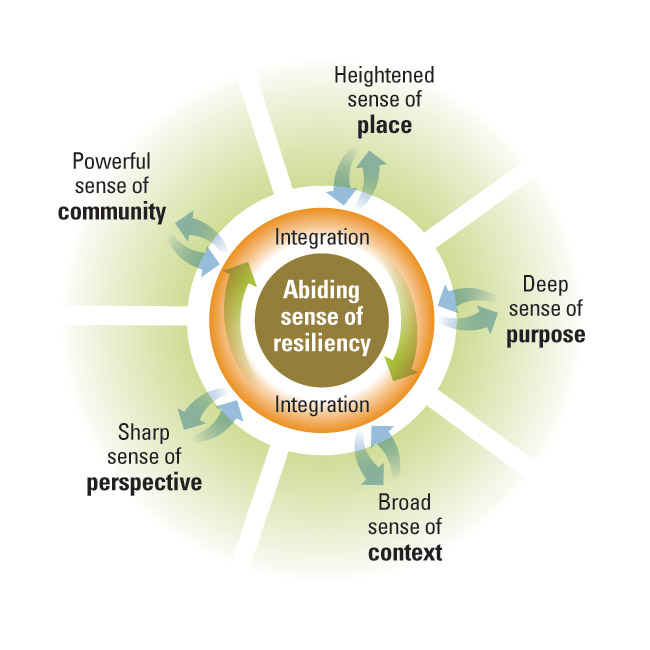

All of the leaders we spoke with indicated that they were already accomplished builders, but mastery of the brokering role is highly dependent on cultivating a new mindset that’s suited to living with the tensions inherent in the job. After analyzing the responses from our interviews, we identified six components of the mindset of the successful enterprise leader: a heightened sense of place; a broad sense of context; a sharp sense of perspective; a powerful sense of community; a deep sense of purpose; and an abiding sense of resiliency. These leaders were not born with such a mindset; they learned how to develop it. (See “Leading With an Enterprise Perspective.”) We’ll look at each of the six components in turn.

Leading With an Enterprise Perspective

Our research suggests six components of the mindset of the successful enterprise leader: a heightened sense of place; a broad sense of context; a sharp sense of perspective; a powerful sense of community; a deep sense of purpose; and an abiding sense of resiliency.

The enterprise leaders we talked to told us that a series of learning opportunities served as enablers for them to develop what we refer to as the six senses of the enterprise leader’s mindset.

1. A Heightened Sense of Place

Many of the enterprise leaders we interviewed referred to their companies as a “special place.” They appreciated the company’s essential identity — so much so that they could tell stories about how the identity served as a source of competitive advantage.12 For Li & Fung’s Raffin, for instance, that identity meant understanding and respecting Frye’s deep history of craftsmanship and what owning a pair of its boots meant to customers. For Unilever’s Gabriel, it meant having a deep understanding of both Unilever’s global reach and what the local products meant to the company’s competitiveness. In the minds of enterprise leaders, the things the company sells are more than products. They are extensions of what the company is and what it is trying to accomplish in the world.

The enterprise leaders developed this sense of place primarily by absorbing the corporate culture.13 Some of this was done explicitly, and it was remarkable how large a role the top leaders played. In interviews with us, both Unilever CEO Paul Polman and Pfizer chairman and CEO Ian Read emphasized their personal involvement. “Leaders often underestimate the enormous influence they have in shaping and bringing to life a company’s culture,” Read told us. For Polman, keeping the focus on the enterprise’s fundamental purpose was the key to transcending a unit viewpoint. “In any important meeting, I tell my team to envision a consumer from an emerging market at the center of the table,” he said. “That consumer might well be a poor woman living under difficult circumstances. If we can make her life a little easier, provide affordable, nutritious food to improve the lives of her family — a family that might be going to bed hungry — maintaining that image makes silo warfare conflicts seem pretty trivial.”

But it was what the top executives did, even more than what they said, that established the sense of place for enterprise leaders. For example, Deepika Rana, Li & Fung’s executive director for the Indian subcontinent and sub-Saharan Africa, spoke about the influence of Li & Fung group chairman William Fung and former group chairman and honorary chairman Victor Fung as role models. “They are big believers in building lean, fast, and agile operations; yet, at the same time, they are also big believers in the importance of cultural integration, of knowledge sharing, and of stressing the importance that Li & Fung’s many local entrepreneurs develop a passion for contributing their know-how to the group’s ambitions.” The point here is not just that the two top executives believe in the dual role; in observing them, Rana realized: “If they can act this way, why shouldn’t I?”

Still, authentic tone setting is not easy for CEOs and executive leadership teams. Most CEOs have to learn to appreciate the power and value of artful brokering among their leadership teams.14 For instance, Leonard Lane, executive director of the Fung Academy and advisor to the chairman, says that William and Victor Fung didn’t always champion building and brokering equally; previously, they focused on growing builders. “If you wanted to learn how to become an entrepreneur, you came to Li & Fung. But the world changed, and our customers wanted more integrated solutions. Our silo-focused entrepreneurs began to recognize the need to collaborate across boundaries to deliver what our customers wanted. That’s when we realized we needed to start developing an enterprise mindset,” he said. William Fung agreed: “We needed to learn how to broker capabilities across the businesses in our network. Once we learned how to do that, the whole network made gains.”

2. A Broad Sense of Context

The enterprise leaders we spoke with demonstrated a comprehensive understanding of the business and how the various pieces of their companies fit together. Their understanding was informed by a variety of postings spanning boundaries of place, unit, and function. Those experiences also widened their worldview, again enabling them to share stories of where and how the companies they worked for fit onto the broader world stage — and why their work is important.

Some of our interviewees spoke of these experiences as intense, crucible assignments.15 Gabriel at Unilever Israel, for example, described a prior assignment as a country manager with a large, global pharmaceutical company, where she had two bosses: one local, the other global. The local boss was focused on maximizing short-term profits, while the global leader was more interested in the big picture and long-term performance. The local manager paid her salary — but the global manager influenced her performance reviews, which also affected her rewards. She had to learn how to balance the inherent tensions — a skill she says prepared her for her current role at Unilever.

As Gabriel’s experience indicates, the value in crossing boundaries is not just the acquisition of experience in different units, functions, or countries but also the chance to learn how to balance competing goals and see how different units, cultures, and ways of thinking fit together and into the wider corporate whole. It was in this spirit that Pfizer’s Gladstone sent his star performer to Japan, expecting that she’d come back with a broader perspective that would be more important to her leadership effectiveness than another position within her own group would have been. She returned to the United States as a more effective listener and adaptive leader, with firsthand experience in how overseas units interact with the “center” and one another. In Gladstone’s view, this has led to more of an enterprise mindset, “less focused on exclusively building her business and more attentive to the workings of the enterprise.”

Unilever pursues a similar philosophy, using short-term assignments under its ambassador program to promote a multifaceted perspective and encouraging enterprise leaders to apply their new experiences to old contexts. Osita Abana, an assistant communications manager from Unilever in Nigeria, was a global ambassador at Save the Children, working to address malnutrition in Bangladesh. He spent a week meeting with health workers and mothers in villages, during which he taught women how to correctly position their babies for breastfeeding and shared ideas for setting up vegetable gardens to grow food for their families and generate income. Such cross-boundary experiences have become a common organizational practice at Unilever.16 As Polman explained, “We broker talent around the world, and I believe there is no better way to develop an enterprise mindset than to see a variety of pieces of the enterprise from a practical perspective.”

Leaders frequently draw on their sense of context when they ask their staffs to roll up their sleeves and make sacrifices. We saw this at Pfizer, where one of the innovative products group’s drug patents would soon expire. Liz Barrett, then president of the company’s innovative pharma division for Europe, shifted it to the established products unit ahead of schedule to give them extra time to develop and execute a marketing plan. The move cost her team revenue and forced a reduction in sales staff, but Barrett concluded that her people’s time was best spent discovering and marketing new products.

3. A Sharp Sense of Perspective

Although a heightened sense of place and a broader sense of context are important, outstanding enterprise leaders also have a sharpened sense of perspective. As Yaw Nsarkoh, managing director of Unilever Nigeria, explained, they see the overall picture but they also appreciate the pixels that make up the picture. Nsarkoh told us that he takes every opportunity to learn from bosses, peers, subordinates, and particularly consumers — which helps him appreciate different management styles instead of forcing his own. He says this is especially critical in a multicultural workplace. Moreover, it informs his view of the company’s role in the market, allowing him to reconcile seemingly conflicting priorities. If a talented employee leaves the company to join a competitor serving the same community, for example, he’ll feel the loss, but he also knows that his former teammate will still be helping Africa.

Most learning takes place through the job assignment.17 But experience goes only so far in developing an enterprise leader’s mindset. The key enablers for gaining perspective are coaching, mentoring, and observation. “We don’t just throw our high-potential enterprise leaders into a job and hope that good things will happen,” said Jonathan Donner, Unilever’s vice president for global learning and capability development. “We identify stretch assignments — then make sure budding leaders are coached and mentored, and networked with other enterprise leaders.”

Certainly, the impact of tone setting, role modeling, and cross-boundary experiences will be diminished if leaders aren’t rewarded for brokering as well as building. This should go without saying, but it can run counter to the prevailing culture — even in the organizations where enterprise leaders thrive. Tanya Clemons, senior vice president and chief talent officer for Pfizer, put it this way: “Our leaders are naturally inclined to be builders. That’s how they have been promoted and rewarded up until now. But we need to begin rewarding them for demonstrating enterprise perspective as well. Inevitably that means rethinking many time-honored review and reward systems.”

Pfizer is taking a more personalized approach. It coaches leaders on how to handle aspects of their jobs that they may have had little experience with. Among them, Clemons says, is understanding the nuances of dealing with the media, with Congress, with analysts, and with community leaders. Constructive and timely feedback can have a powerful effect on aspiring leaders and can motivate them to be similarly positive with their own people.18 At Frye, Raffin credits feedback from a former boss with helping him sharpen his enterprise perspective, which he in turn attempts to pass on to others: “I used to be a command and control manager … [and] I used to hoard knowledge. But now I share it. I share what’s happening in the group head office at Li & Fung and then try to align those challenges with ours at Frye. And now it’s not just me. We have created a culture and a mindset where knowledge is brokered for positive action. Every team member has an accountability to listen, to translate, and to act.”

It’s important to note that leaders don’t just benefit from coaching and mentoring from above; as many note, they have also been students of peers and subordinates. As Unilever Nigeria’s Nsarkoh put it: “I have learned from Unilever’s senior executives, but I have also learned from factory workers. I have learned from listening to people — in trying to understand what causes their behavior — then trying my best to help them do their best.”

4. A Powerful Sense of Community

We know from our prior research on high-potential talent that people are drawn to peer networks that challenge and support them.19 The same is true for senior-level enterprise leaders. And savvy companies don’t leave those connections to chance. Rather, they enable the creation of peer-learning networks where enterprise leaders can discuss key challenges with others, find kindred spirits, and get help.20 Even though leaders we spoke to indicated that they spend a great deal of time cultivating their personal and professional networks, we also found examples of company-designed initiatives that helped senior executives build a powerful sense of community and distributed leadership. In such instances, the process of learning together was at least as important as the content components.21

At Pfizer, for example, the Chairman’s Challenge program enables a select group of senior-level enterprise leaders to interact with the chairman and the executive committee and to be part of an intensive peer-learning group. Cohort groups of 12 spend a little more than a year focusing on a particular business challenge and working closely with executives inside and outside the company to develop solutions. For example, working with a nongovernmental organization, a recent group studied health care needs in emerging markets. Although the project entailed a significant investment of time, one participant called it “great team building beyond what would have happened through any other program.”

Facing a different set of challenges, Li & Fung has oriented its learning program for enterprise leaders differently. Since many of its leaders are accustomed to operating opportunistically in emerging markets, the program provides formalized management and leadership training along with specific instruction on topics such as influencing without authority, managing in a global matrix, the art of persuasion, communication skills, and mobilizing teams.

5. A Deep Sense of Purpose

Enterprise leaders expressed exceptional passion about their careers and their companies. Many of the enterprise leaders we interviewed became emotional when talking about their roles and the impact they were having on other people’s lives. That’s partly due to the personal fulfillment these people found in their work but even more the result of their reflection, introspection, and willingness to change as leaders.

Polman, for instance, is strongly committed to environmental sustainability while also pursuing a path of growth. He promotes both themes through the company’s strategy statements, values, and management practices. The commitment to both sustainability and growth can pose challenges for Unilever’s managers. In procurement, for instance, factoring sustainability into decisions can drive up costs even as employees are expected to manage costs. In the face of conflicts, employees are expected to elevate decisions to an organizational level where managers have the authority to consider the trade-offs of adhering to Unilever’s purpose while remaining fiscally responsible. “People want to work for a company with a sense of purpose,” Polman told us.

Leaders don’t just benefit from coaching and mentoring from above; as many note, they have also been students of peers and subordinates.

At Li & Fung, the founders’ sense of purpose serves to inspire employees in their work. Over the years, Rana told us, the Fung brothers set an example of being loyal to their employees and putting people first. In addition to being results-driven, the brothers also demonstrate a “softer, more human side” that is integrated into the way Li & Fung functions. In particular, they show a sincere commitment to family values.

“I have seen many examples of the Fung principles guiding behaviors,” Rana says. “I would get personal calls from either of the brothers checking up on an employee’s wife, child, or parent. They have set an example of leading from the front and are building a top-down and bottom-up belief in the culture and values of the company. [They] have long stated that their people are their biggest asset, and they have used this asset to leapfrog into success over the last decade.” Rather than influencing employees through individual speeches or stories, the everyday connections between the CEO’s sense of purpose and the corporate vision form indelible impressions about what’s important.

6. An Abiding Sense of Resiliency

Many of the top leaders we interviewed spoke about the importance of building a cadre of enterprise leaders who not only are committed to continuous improvement but demonstrate a remarkably high level of personal resiliency. “We need to create an organization that is fit for the future, and to do that we need leaders who are fit for the future,” Unilever’s Polman noted. “We can’t build a next-generation company with a last-generation leadership mindset.”

One Unilever enterprise leader who exhibits what Polman was talking about is Laurent Kleitman, the CEO of Unilever Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus. While managing Unilever’s business in Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and Turkey in 2009, Kleitman was hired away by another large consumer products company. However, after three years with the new company, he returned to Unilever. “What I missed was how much trust our senior leaders place in people to do the right thing for our consumers,” Kleitman explained. “If conditions on the ground change here — and believe me, they change a lot in this region — I am empowered to change our processes overnight if necessary.”

What we’re describing is distinct from the call for greater organizational agility, so often heard as an answer to increased competitive complexity. Agility is critical, to be sure, but it is an organizational capability.22 The people we talked to played key roles in building agile organizations, and in so doing demonstrated their capacity to be resilient. They were able to pick themselves and others up after stumbling and, more importantly, to pivot to the future.

How do Kleitman and other effective enterprise leaders we studied manage to see the importance of the micro and the macro simultaneously? By relying on the mindset and the senses we have discussed.23 Belief that they are part of purpose-driven enterprises enables them to focus on the big picture and resist “sweating the small stuff.”24 Their exposure to a variety of cultures and different business conditions helps them to abandon one-size-fits-all thinking. Their trust in their leaders and their peers enables them to share successes and combat difficulties together.25 They learn from their mistakes, they change, and they grow.

As Bill Carapezzi, Pfizer’s senior vice president for finance and global operations and one of its enterprise leaders, put it: “The way I felt about myself and the negative relationships I developed working with people with a territorial approach was no fun. I was just like everyone else around me — I was a silo leader. Everybody was watching the borders. As I learned to work in a new way at Pfizer, I developed better relationships and learned how to mobilize my team for the greater good, which enabled me to deliver more value for the company, and I just felt better.”

References

1. “About Us,” 2015, www.unilever.com.

2. D.A. Ready and M.E. Peebles, International Consortium for Executive Development Research (ICEDR)-sponsored research on enterprise leaders, June-August 2014.

3. Ibid.

4. D. Midgley, “Understanding Customers in the Solution Economy,” August 24, 2012, http://hbr.org.

5. J.I. Cash, Jr., M.J. Earl, and R. Morison, “Teaming Up to Crack Innovation and Enterprise Integration,” Harvard Business Review 86, no. 11 (November 2008): 90-100.

6. Ready and Peebles, ICEDR-sponsored research.

7. D.A. Ready, “Leading at the Enterprise Level,” MIT Sloan Management Review 45, no. 3 (spring 2004): 87-91.

8. L.A. Hill, “Becoming a Manager: How New Managers Master the Challenges of Leadership” (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2003).

9. “About Us,” 2015, www.lifung.com.

10. M. Kristal, “Frye: The Boots That Made History — 150 Years of Craftsmanship” (New York: Rizzoli, 2013).

11. D.L. Dotlich, P.C. Cairo, and C. Cowan, “The Unfinished Leader: Balancing Contradictory Answers to Unsolvable Problems” (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2014).

12. T.J. Erickson and L. Gratton, “What It Means to Work Here,” Harvard Business Review 85, no. 3 (March 2007): 104-112.

13. E.H. Schein, “Organizational Culture and Leadership” (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1985).

14. B. George and P. Sims, “True North: Discover Your Authentic Leadership” (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2007).

15. W.G. Bennis and R.J. Thomas, “Geeks and Geezers: How Era, Values, and Defining Moments Shape Leaders” (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2002).

16. W.W. George, K.G. Palepu, C.I. Knoop, and M. Preble, “Unilever’s Paul Polman: Developing Global Leaders,” Harvard Business School case no 413-097 (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2013).

17. M.W. McCall, Jr., M.M. Lombardo, and A.M. Morrison, “The Lessons of Experience: How Successful Executives Develop on the Job” (New York: Free Press, 1988).

18. M. Goldsmith and M. Reiter, “What Got You Here Won’t Get You There: How Successful People Become Even More Successful” (New York: Hyperion, 2007).

19. D.A. Ready, J.A. Conger, and L.A. Hill, “Are You a High Potential?” Harvard Business Review 88, no. 6 (June 2010): 78-84.

20. M.W. McCall, Jr., “High Flyers: Developing the Next Generation of Leaders” (Boston: Harvard Business Review Press, 1998).

21. D.A. Ready, “How Storytelling Builds Next-Generation Leaders,” MIT Sloan Management Review 43, no. 4 (summer 2002): 63-69; D. Ancona, T.W. Malone, W.J. Orlikowski, and P.M. Senge, “In Praise of the Incomplete Leader,” Harvard Business Review 85, no. 2 (February 2007): 92-100; and J.P. Spillane, “Distributed Leadership” (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2006).

22. R.A. Shafer, L. Dyer, J. Kilty, J. Amos, and G.A. Ericksen, “Crafting a Human Resource Strategy to Foster Organizational Agility: A Case Study,” working paper 00-08, Cornell University, School of Industrial and Labor Relations, Center for Advanced Human Resource Studies, Ithaca, New York, 2000.

23. R.L. Martin, “The Opposable Mind: Winning Through Integrative Thinking” (Boston: Harvard Business Review Press, 2007).

24. J. Kurtzman, “Common Purpose: How Great Leaders Get Organizations to Achieve the Extraordinary” (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2010).

25. M.M. Pillutla, D. Malhotra, and J.K. Murnighan, “Attributions of Trust and the Calculus of Reciprocity,” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 39, no. 5 (September 2003): 448-455.

View Exhibit

View Exhibit View Exhibit

View Exhibit