And in the fifth decade of Modernism Le Corbusier said “Let there be concrete”: and there was Brutalism.

Well, perhaps not quite. However the Swiss-French polymath certainly kick-started what became the most divisive school of architecture in the twentieth century. His buildings from the late 1940s onwards paved the way for a new brand of Modernism, employing “beton brut”, raw, unfinished concrete set in bold, geometric forms. Form followed function and the result was monolithic, imposing and disruptive.

Brutalism had its admirers, but there were detractors, a group whose voice swelled down the years as buildings fell into disrepair and the aesthetic became a byword for poverty, antisocial behavior and poor urban planning. Some buildings are now living on the brink; others are have already been demolished.

But whisper it quietly: Brutalism is having a moment.

New buildings on the block

Peter Chadwick and Nicolas Grospierre are two authors waving the flag for these hunks of concrete. Chadwick’s “This Brutal World” focuses solely on the aesthetic, whilst Grospierre’s photobook “Modern Forms: A Subjective Atlas of 20th-Century Architecture” covers Brutalism in a wider context of nearly 200 buildings.

What both have done is sought beauty where many forgot it could be found. From residential towers in St Petersburg to chapels in Acapulco, Chadwick and Grospierre have illustrated the global reach of beton brut. Surprisingly, it’s a canon that continues to grow according to Chadwick.

“When we sat down to talk about the book we looked at the more historic architecture within the canon of Brutalism,” he says, referring to his publisher Phaidon. “But we also looked at how contemporary architects were visually inspired by the elder Brutalist buildings.”

That’s why you’ll find new builds from OMA and Zaha Hadid’s Pierresvives (2012) in his volume. “Her structures were underpinned with some very raw concrete features… there was a strong link to be made and we wanted to represent that in the book,” Chadwick argues.

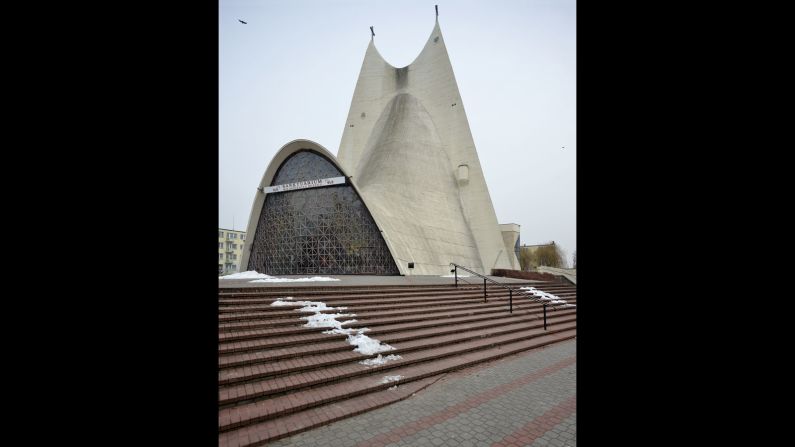

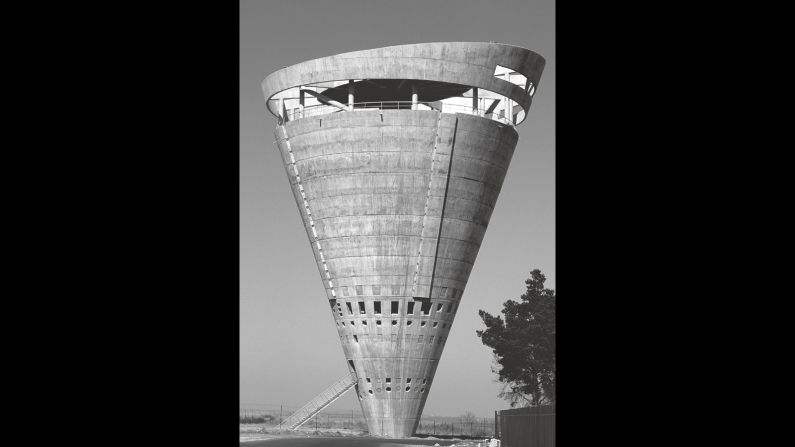

Photographer Grospierre chose to look for gems in Poland and the former Eastern Bloc, among 20 countries featured in “Modern Forms”. “There was this sense of discovery with completely unknown architecture,” he recalls. “By accident I stumbled across some quite extraordinary examples from late Modernism.”

Rather than plot his findings on a timeline, Grospierre has chosen to place his photography on something akin to an aesthetic continuum, matching the succeeding building to the shape and style of that which precedes it. The result is a globe-hopping journey of domes into triangles, triangles into cubes, cubes into asymmetrical roofs and so on, each building leeching on those around it.

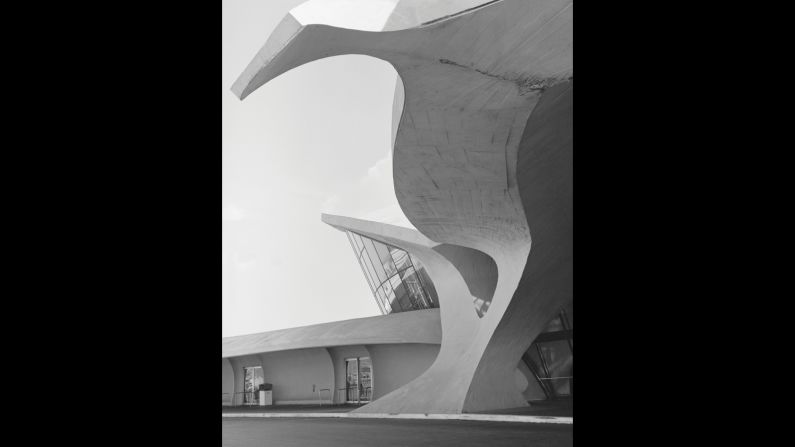

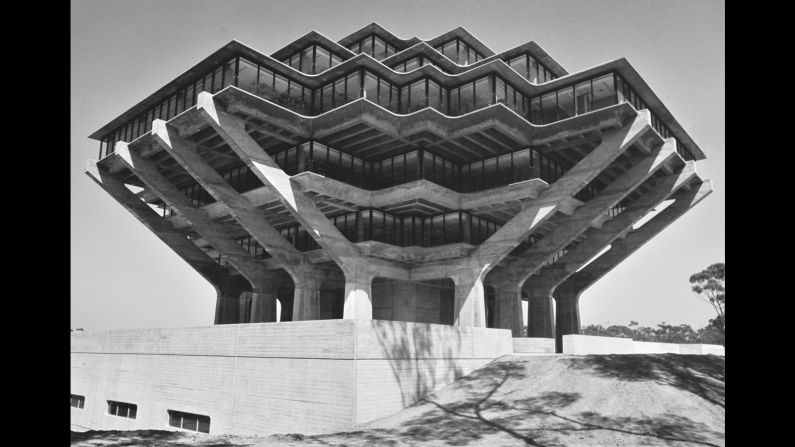

The osmosis-like layout of “Modern Forms” reinforces the ties that bind the school of architecture. “This Brutal World” however relies on monochrome images to link the works of numerous photographers.

Luckily Brutalist buildings look great in black and white, says Chadwick. “You get a very strong sense of shape, composition… it’s all about light and shadow. When you look at the National Theatre on the Southbank on a sunny day, when you see the shadows it’s just incredible. It’s like architectural theater, and that’s only enhanced by black and white.”

A movement not without its problems

Neither Grospierre nor Chadwick shy away from explaining why Brutalism gets its bad rep. Moreover, they both suggest criticism levied against the aesthetic is often valid. Not all Brutalist creations were made equal, they suggest, and for every great building there was another ready to undermine the movement.

Brutalism’s functionality made it the perfect fit for cash-strapped post-war Europe, seeking to rebuild urban centres for swelling populations. It became the aesthetic of choice for many low-cost housing projects and in Western Europe Brutalism became a symbol of poverty. In Eastern Europe this was compounded; elision between projects and the governments that commissioned them often precluded appreciation of Brutalism’s merits.

“A lot of post-war developments were really badly designed and badly maintained housing estates,” says Chadwick. Grospierre concurs, reflecting that in Poland there are numerous “large-scale housing estates done very cheaply.”

“Flats, many stories up, don’t have direct access to outside space, so the ‘outside’ is on the ground level,” Chadwick explains. “There’s these negative, redundant spaces around the building, which prompts anti-social behavior. Brutalism has suffered because of this.”

Then there is the perception that these vast walls of unfinished concrete “can feel a bit like a playground bully,” says Chadwick. “I think it’s a question of weight,” argues Grospierre, “of the visual impact that the work produces.” And when the balance tips too far towards incongruity, critics will weigh in.

Grospierre suggests that at the heart of the matter is the problem that “Brutalism is more of an aesthetic choice, rather than programmatic… I think Modernism has this social program which Brutalism does not, per se.” And so whilst Grospierre sees Modernism as a utopian project, “the embodiment of an idea of progress – a certain type of progress – abandoned over 30 years ago,” Brutalism is “simply taking advantage of concrete technology.”

An unlikely revival

Perhaps paradoxically, Chadwick suggests that “concrete is delicate.” In “This Brutal World” he cites Ivan Locke, a character played by Tom Hardy in the film “Locke” (2013), who describes concrete as “delicate as blood.” Meanwhile “High-Rise” (2016), an adaptation of JG Ballard’s novel by director Ben Wheatley, is bringing Brutalism back into popular culture.

So is it cool to like these buildings once more?

“I think it is, yes,” says Grospierre. Chadwick agrees. Perhaps they’re not the most unbiased opinions to reach out for, but there’s an overarching reason, the latter suggests.

“I think people of my age have this nostalgic response to Brutalism that takes them back to my childhood,” he says. Chadwick, in his forties, is a child from the same era as Ballard’s “High-Rise”, when the concrete was freshly-set and damp-free. Now people of the same age are watching relics of their childhood crumble and moulder.

For Grospierre it is part of their appeal, in that “somehow the state of these buildings are a good representation of [the failure of progress].” Chadwick however looks on with horror.

“Unfortunately it’s a lot more expensive to preserve the buildings than to knock them down and build something else in their place,” he explains.

“[Brutalism] is definitely having its moment, which is great. I just hope it continues, the interest and the preservation of buildings, before we lose any more.”

“Modern Forms: A Subjective Atlas of 20th-Century Architecture” by Nicholas Grospierre is published by Prestel; “This Brutal World” by Peter Chadwick is published by Phaidon. Both are out now.

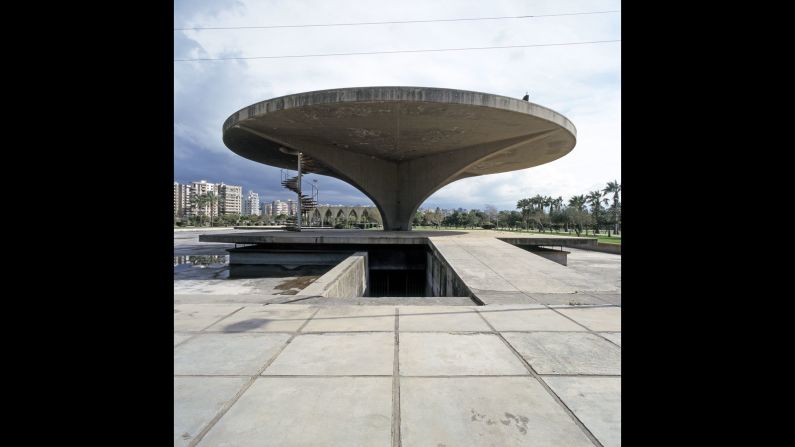

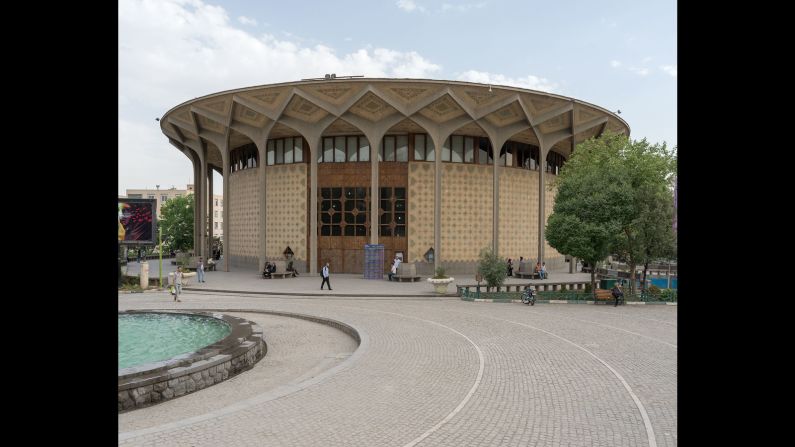

![Grospierre manages to sandwich obscure, UFO-shaped buildings such as the Institute of Scientific Research and Development in Kiev, between builds in Iran and Poland. The authors suggests imposing works such as the Institute must toe a certain line with their surrounding, saying "it's a question of weight [and] of the visual impact the work produces."](https://media.cnn.com/api/v1/images/stellar/prod/160420121056-modern-forms-1.jpg?q=w_1600,h_900,x_0,y_0,c_fill/h_447)