Gwynne Lewis, who has died aged 81, was a leading historian of the French Revolution. A political radical, he could readily identify with the sans-culottes – the poorer revolutionaries whose menfolk wore trousers rather than the knee-breeches of the middle or upper classes, and who nurtured proto-socialist aims. His books Life in Revolutionary France (1971), The French Revolution: Rethinking the Debate (1993) and France 1715-1804: Power and the People (2004) viewed events from the point of view of social history, even as this approach was coming under attack from revisionist and cultural historians.

For Gwynne, the revisionists were wrong in viewing politics rather than social tensions as the root cause of the revolution, and while many cultural historians seemed to doubt the very existence of social classes, Gwynne argued against that. He resisted dogmatic Marxism, but admired the sympathetic portrait of the sans-culottes by the Sorbonne professor and communist militant Albert Soboul. Yet while Soboul and his Marxist confreres highlighted moments of great political intensity in Paris during the Terror (1793-94), Gwynne held that class tensions usually worked themselves out over time. He thus highlighted the need to take the long view when studying the revolution, and focused on the provinces – on which he did his best work.

Unlike the Marxists of his day, he also cast a sympathetic, sometimes sentimental, eye over popular royalists and counter-revolutionaries, seeing their protests against bourgeois politics and commercial capitalism as every bit as legitimate and worth studying as those of Parisian radicals. Whatever their political complexion, it was the poor who were left to pick up the pieces after any revolutionary conflagration, “paid for in their own blood”, he lamented.

Although his Welsh grandmother had told him as a child that he was descended from Welsh princes, Gwynne had little time for the powers that be. Born in Merthyr Tydfil, Glamorgan, he reflected in his life much of the social change of modern Wales. The son of a Baptist minister to Welsh-speaking congregations, the Rev Dewi Lewis, and his wife, Elizabeth Owen, as an adult Gwynne would become an atheist and also lose his childhood Welsh. From Pontypridd grammar school he went briefly to theological college at the age of 18, and after a series of short jobs took a BA in history at University College Wales, Aberystwyth (now Aberystwyth University), an MA at Manchester University and a DPhil at Oxford, before returning to Aberystwyth as a lecturer in 1963. In 1968 he joined the history department at Warwick, where he was appointed professor in 1984 and remained until retirement in 1997, with years abroad at Kingston University, Ontario, and the University of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. He was latterly also director of the Warwick Centre for Social History.

Gwynne was a brilliant lecturer who made full use of the Welsh tradition of wit and eloquence. He recalled going to a seminar held in Paris by Soboul, who would jab his finger as he tested his audience: “Now Monsieur Lewis, you will ask a question!” Other influences included Richard Cobb, notably for his engagement with “history from below”, and EP Thompson, author of The Making of the English Working Class and, briefly, a Warwick colleague. Like them, Gwynne liked getting his hands dirty in archives and based two books on those of the department of the Gard. The Second Vendée (1978) explored the experience of the area’s many Protestants during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic periods, while The Advent of Modern Capitalism in France 1770-1840 (1993) was a study of Pierre-François Tubeuf, whose founding of a modern coalmining industry paralleled the story of Gwynne’s native south Wales.

At the start of the 1970s Gwynne was one of many at Warwick who protested about what Thompson called an attempt to make it a “business university”. Later Gwynne reacted strongly to changes in educational planning, introduced by the Labour government of James Callaghan, that he saw as corrosive of academic autonomy and continuing the trend to favour utilitarian considerations over intellectual concerns.

For most of his life he was a caustic Labour critic of Welsh nationalism and language revivalism, but softened this view in later years.

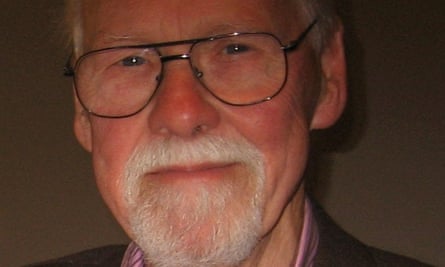

Warm and rumbustious in all his dealings, Gwynne was a man of strong build and presence, an accomplished actor in his youth and an all-round sportsman with a continuing devotion to table tennis and Welsh rugby.

In 1960 he married Madeline Rosser. She died in 2006. He is survived by his children, Martyn, Rachel and David.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion