Robert Clatworthy, who has died aged 87, was a fine sculptor whose career began in metropolitan renown and ended obscurely in mid-Wales. Although his latter years were spent in self-imposed isolation, they were far from unproductive, and he continued to make highly abstracted works that were at least as challenging as those of his youth. Indeed his late Heads, with their splintered forms and pitted surfaces, were unsurpassed in their physical and psychological power. Clatworthy’s creative vigour lasted to the end, even when changes in fashion, combined with his own recalcitrance, consigned him to the margins of the art world.

Robert, son of Ernest, a railwayman, and his wife, Gladys (nee Jugaler), was born in Bridgwater, Somerset, and went to Dr Morgan’s grammar school. Rural life in the West Country was to inspire his interest in animal sculpture and he remained in the region for his first spell at art school in the mid-40s, studying at the West of England College of Art in Bristol. Towards the end of the decade, after a period in national service, Clatworthy attended Chelsea School of Art, London, where he was taught by Bernard Meadows. He also began an enduring friendship with Elisabeth Frink, whose work he continued to praise even when she later eclipsed him.

In the early 50s Clatworthy had an important break, being taken on as an assistant by Henry Moore, who gave him a surprising degree of creative latitude. Moore also persuaded him to join the Slade School in preference to the Royal College of Art, a decision that he is said to have regretted, though it did not hinder his early success.

The young Clatworthy was extrovert, even charismatic. In 1954 he married the actress Pamela Gordon, the daughter of the musical performer Gertrude Lawrence, while also making rapid advances into the West End art scene. As a rising star at the Hanover Gallery he showed his menacing bronzes of bulls and cats, whose textured surfaces express his rapid handling of the quick-drying plaster from which they were cast. Later, in 1965, he exhibited at the Waddington Galleries his austere standing and walking figures, which evoke Alberto Giacometti and Germaine Richier.

Certainly, Clatworthy was in tune with the postwar zeitgeist. In the mid-50s the critic David Sylvester, who was also close to Clatworthy’s friend and drinking partner Francis Bacon, described his output as “the best thing I have seen by any English sculptor younger than Henry Moore”. However, even at the height of his commercial success, he believed in following his own rhythms rather than the demands of the art market, and he eventually fell out with his fashionable dealers over their requests for constant production.

An even more serious problem, faced by many artists in the late 60s and early 70s, was the declining interest in figurative art. Clatworthy attempted to accommodate this shift in taste by creating hard-edged, totem-like objects in fibreglass. This development was not a success, and he never again departed from his idiom of stylised natural forms.

Despite, or perhaps because of, his fall in popularity, Clatworthy pursued a career in teaching, starting in the 60s with the Royal College of Art, followed by the West of England College of Art and St Martin’s School of Art, London. This part of his career culminated, between 1971 and 1975, in the post of head of the fine art department at the Central School of Art and Design, London. He also was elected to full membership of the Royal Academy of Arts at the age of 45, and took part in group exhibitions, notably British Sculpture in the 60s at the Tate Gallery (1965), and, seven years later, British Sculptors 72 at the RA.

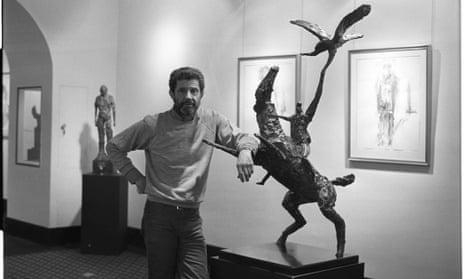

In the first half of the 80s, Clatworthy, newly reinvigorated, produced some important works, such as the monumental Horseman and Eagle, originally commissioned for an office block at 1 Finsbury Avenue in London, but later installed in a sunken garden at Charing Cross hospital, Hammersmith. It is perhaps his most accessible large-scale sculpture, notwithstanding the magnificent bull, made almost 30 years earlier for London county council, at Alton Estate in Roehampton. There are also smaller pieces in the Tate, V&A and Art Council collection, as well as the National Portrait Gallery, which holds his naturalistic bust of Frink (1983).

The last three decades of Clatworthy’s life were based near Llandovery in the interior of Carmarthenshire, where he lived with his second wife, Jane Stubbs, whom he married in 1989. This period was characterised by an almost monastic approach to work, even when he was obliged by a skin condition in the 90s to concentrate on painting and drawing rather than sculpting plaster. He rose at 4.30am every day, including Christmas, lunched and dined at correspondingly early hours and would say almost nothing about his art.

Clatworthy remained tight-lipped when the collector and dealer Keith Chapman edited an authoritative book about his sculptures and drawings in 2012, and was less than friendly to potential customers, apparently to the extent of burying bronzes in the garden. Although such behaviour may seem eccentric, it was entirely consistent with his overriding aim – to concentrate on the act of sculpture, to the utter disregard of commerce, posterity or the infrastructure of the contemporary art world.

He is survived by Jane, and by the children of his first marriage, Ben, Sarah and Tom.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion