Newly published documents obtained by whistleblower Edward Snowden have revealed the extent of a plot involving the British government’s successful infiltration of Belgium’s largest telecommunications provider.

According to a report in the Intercept, which houses the classified materials obtained by Snowden from the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA), the British government intentionally compromised Belgium’s national telecom service, Belgacom, in order to “spy on phones used by surveillance targets traveling in Europe and to break data links connecting Belgacom and its international partners.”

The British government’s hand in the attack was first revealed in September by German magazine Der Spiegel, which claimed the goal of the project, codenamed “Operation Socialist,” was to “enable better exploitation of Belgacom.” The Intercept’s report, published online Saturday morning, expands upon the British government’s role, referred to by Snowden as the “first documented example to show one EU member state mounting a cyber attack on another.”

Belgacom has millions of customers across Europe and its partners include hundreds of telecom companies in Africa, Asia, Europe, the Middle East and the United States. Countless individuals rely on Belgacom’s networks while traveling through Europe, the Intercept notes, making it an ideal target for spy agencies.

GCHQ's explicit goal was to completely own Belgacom and then see what other telecoms they could own from there. pic.twitter.com/F1U9VpMlYV

— ageis (@ageis) December 13, 2014

To effectively compromise Belgacom’s networks, Britain’s top spy agency, the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), is accused of employing the malicious software now known as Regin, which is thought to have been used since at least 2008 in numerous spying campaigns targeting international governments.

Security experts have acknowledge Regin’s “rarely seen” advanced design and noted its extensive capabilities and powerful framework for mass surveillance.

“It is likely that its development took months, if not years, to complete and its authors have gone to great lengths to cover its tracks,” American security firm Symantec stated last month. “Its capabilities and the level of resources behind Regin indicate that it is one of the main cyberespionage tools used by a nation state.”

A November report by Kaspersky Lab identified among Regin’s past targets: multinational political bodies, individuals involved in advanced mathematical and cryptographic research, and institutions of government, finance and research. The malware is designed, experts say, to gather intelligence and create vulnerabilities that can be exploited by future attacks.

Since Der Spiegel’s report, Belgacom has remained tight-lipped about the degree to which its systems were effected. According to classified documents, however, the company’s silence may be the result of an unprecedented collapse in security, which permitted British spies to capture streams of both encrypted and unencrypted communications.

"end goal has been access to routers that can used as platforms for MitM operations against mobile handsets" pic.twitter.com/BAPci48jVb

— ageis (@ageis) December 13, 2014

While Belgacom has spent millions in an effort to refortify its network, the Intercept reports that sources familiar with the company’s investigation are not convinced the GCHQ’s eavesdropping software has been adequately purged.

The GCHQ reportedly began development on new invasive methods for eavesdropping on telecom networks in 2009, when such attacks were discussed at conferences held by an international surveillance partnership—including agencies of the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada—known collectively as the “Five Eyes.”

“[T]he agency wanted to adopt the aggressive new methods in part to counter the use of privacy-protecting encryption—what it described as the ‘encryption problem,'” the Intercept reports. This was reportedly accomplished by targeting three specific Belgacom engineers. After the malware was successfully installed on their computers, GCHQ was able to exploit the engineers’ high-level privilege within Belgacom’s network.

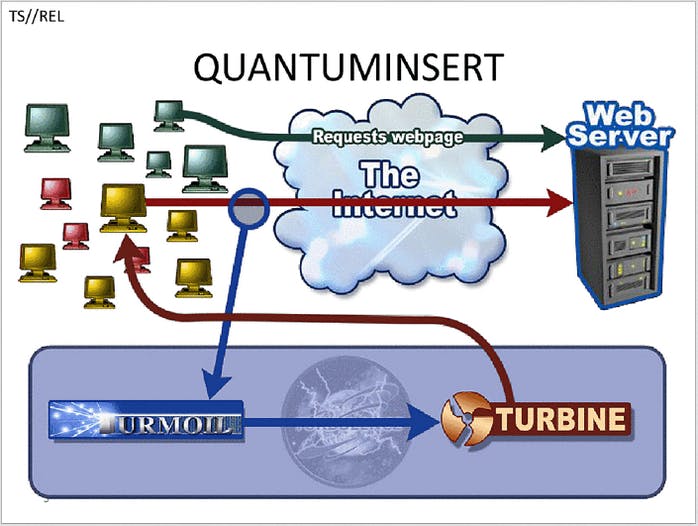

GCHQ relied on a form of phishing, or masquerading as an honest service, to initially compromise the engineers. The three reportedly fell victim to a “quantum insert” attack which involved infecting their machines with malware after redirecting them to a fake LinkedIn website. Similar attacks were utilized by the NSA, the Intercept previously reported, which used a fake Facebook server to infect users and surreptitiously exfiltrate data.

The extent of the GCHQ’s attack was not known until mid-2013 when a forensic investigation revealed that sophisticated malware had infected more than 120 Belgacom computer systems, including the Cisco routers at the core of the company’s international networks. Although the Intercept could not report with certainty that the routers themselves were tampered with, it pointed to earlier reports that reveal how the NSA, an agency with abilities comparable to GCHQ, was able to physically intercept and modify similar devices in transit.

“The secret British infiltration of Belgacom is an unprecedented example of a cyberattack on the infrastructure of a closely allied country,” the Intercept concluded. “Last year, Belgium’s prime minister said that if it were confirmed, it would represent a violation of the public company’s integrity.”

Despite the severity of the accusation against the British government, it declined to comment on the Intercept’s report, insisting that its actions remain legal and necessary.

Photo by arthur-caranta/Flickr (CC BY SA 2.0)