Current affairs and children’s programmes produced by the BBC are unlikely to form part of the corporation’s proposed “competition revolution”, avoiding the biggest upheaval in BBC production for a generation.

BBC executives led by director general Tony Hall are understood to have decided that news and current affairs will be excluded from plans under which the corporation’s in-house programme-making departments, responsible for shows ranging from Doctor Who and Silent Witness to Top Gear, would for the first time be given free rein to produce programmes for other channels in the UK and around the world. The news is likely to come as a relief to in-house producers in news and current affairs as well as the childrens’ department which are less attractive to commercial rivals.

Senior sources at the BBC say that the business case is “less clear cut” for childrens’ production, a market the BBC dominates. There is very little homegrown children’s television made, especially drama for example, in a market which is dominated by a handful of huge American companies such as Nickelodeon and Disney.

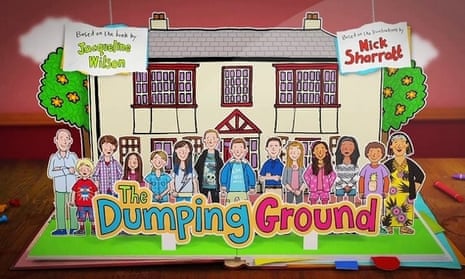

ITV and Channel 5 produce very little children’s programming in-house while Channel 4 is committed to serving the 10-14 market which it largely does by commissioning drama series Youngers. The two BBC channels commission many independent producers as well as the BBC’s own The Dumping Ground, Hackertime and Sam and Mark’s big Friday Wind Up.

Greg Childs, who headed the launch team for BBC Children’s channels, CBBC and CBeebies, and is now director of the children’s media foundation, said: “The BBC is the only game in town, certainly the only big player in town.”

The suggestion that the children’s department will have to compete in such a limited external market has caused some concern. Childs half jokingly called the plans, laid out by Hall in a speech last summer, as “the semi-privatisation of the production department”.

The BBC has refused to rule out any departments officially but privately executives are understood to believe that certain sectors are more difficult to sell to rivals than others. Drama, entertainment and natural history are among those most likely to be able to benefit from being able to sell their ideas and productions to external commissioners.

In his speech launching the plans, Hall said: “If independent producers can take their ideas to any broadcaster around the world, I would want the same for the BBC. Proper competition and entrepreneurialism requires a level playing field. We should have regulation in the TV supply market only where it’s needed so that we can let creativity flourish … A level playing field doesn’t tilt.”

Many observers felt that relatively controversial programmes such as the recent legally contentious report on Mazheer Mahmoud, for example, underlined how difficult it would be to expect in-house producers to flog their programmes outside the BBC. The decision to run the programme was made by the editor Ceri Thomas with the direct backing of James Harding, the BBC’s head of news, as well as Hall.

Hall believes that greater competition will be good for the BBC and has introduced a corporation mantra of “compete or compare” in an attempt to reduce costs and encourage innovation. Even if not made to “compete” under the new proposals, all BBC departments will still be forced to submit to comparison exercises to check for value for money under the groundbreaking new structure expected to be set out in full as part of charter renewal negotiations after the general election.

The BBC’s in-house production departments have cut back their full time staff numbers significantly in the past two decades, and along with the rest of the industry rely more heavily on freelance and contract employees. However, the BBC remains one of world’s largest TV production studios, with about 2,500 staff.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion