The Cognitive Benefits of Doodling

Some new books tout the benefits of informal drawing and freehand scribbling—even for the unartistic.

When computers entered the mainstream, some art schools abandoned drawing classes to make time for the new software they had to teach. The arrival of state-of-the-art programs prompted backlash among those who’d argued for years that drawing is integral to literacy. “When you draw an object, the mind becomes deeply, intensely attentive,” says the designer Milton Glaser, an author of a 2008 monograph titled Drawing Is Thinking. “And it’s that act of attention that allows you to really grasp something, to become fully conscious of it.” Anyone who has put pen or pencil to paper knows exactly what Glaser is talking about.

Two new books tout the benefits of drawing, sketching, and doodling as tools to facilitate thinking. While a spate of branded and bespoke blank sketchbooks, journals, and pads meant for drawing are also sparking something of a renewed interest in the practice. Perhaps it’s a kind of artistic rebellion over the supremacy of computers and digital media. Or, maybe the need to draw is simply hardwired into human brains. Arguably, making graphic marks predates verbal language, so whether as a simple doodle or a more deliberate free-hand drawing, the act is essential to expressing spontaneous concepts and emotions.

Drawing with pencil, pen, or brush on paper isn’t just for artists. For anyone who actively exercises the brain, doodling and drawing are ideal for making ideas tangible. What’s more, according to a study published in the Journal of Applied Cognitive Psychology, doodlers find it easier to recall dull information (even 29 percent more) than non-doodlers, because the latter are more likely to daydream.

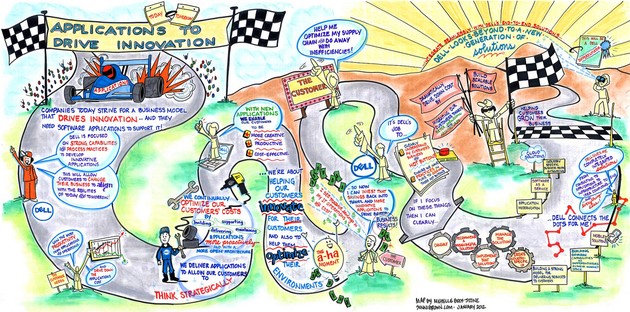

While drawing is definitely the artist’s stock and trade, everyone can make doodles, bypassing the kind of refinement demanded of the artist. Drawing, even in a primitive way, often triggers insights and discoveries that aren’t possible through words alone. Just think of all those napkins (or Post-Its) on which million-dollar ideas were sketched out.

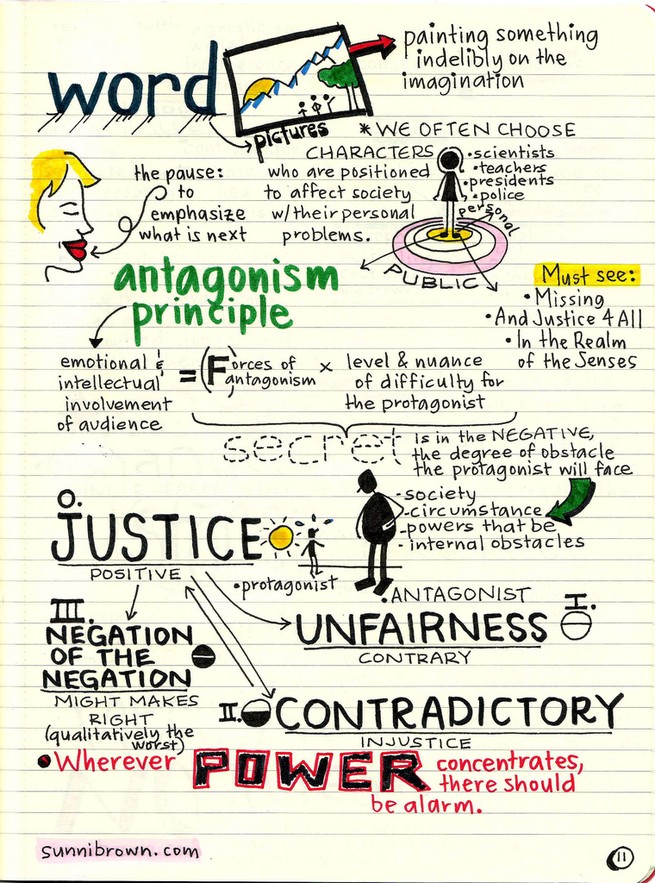

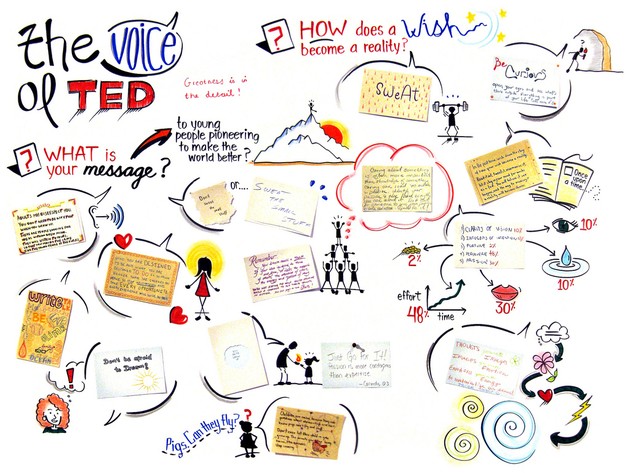

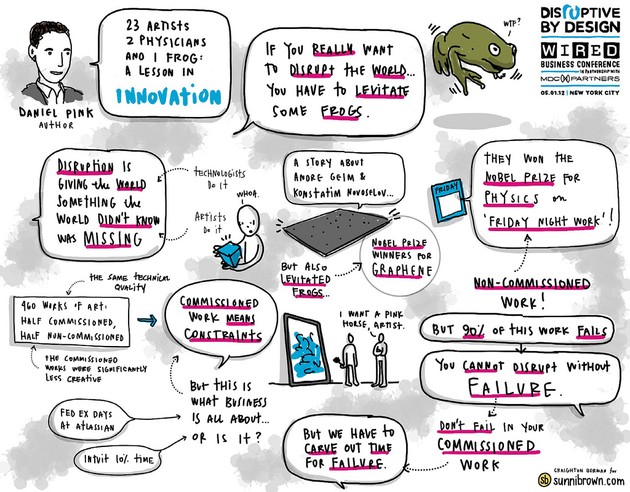

“I give no points for the aesthetic quality of a doodle,” says Sunni Brown, author of the recently published The Doodle Revolution, about developing concepts through pictures, “because the perceived skill has absolutely nothing to do with the quality of the learning experience for the doodler.” A picture that’s utterly hideous may still have taught the creator something significant. Learning, not aesthetic sophistication, is the goal. Brown isn’t keen on “highly skillful doodlers” because she thinks visual language should be open to those who lack the talent or ability. In her role as doodle advocate, Brown believes that to make the practice into something that requires savvy would be as dangerous as suggesting that only people who excel at writing should ever compose sentences.

Brown’s own relationship with doodling came later in life. Growing up, her doodles showed up mostly in the margins of notebooks. But while working at a consultancy firm called The Grove, in San Francisco, she “was re-introduced to simple, applied visual language as a form of thought.” After launching her own creative consultancy in 2008, she used the term doodling for this form of applied visual language and referred to it as an “act of cognition.” And she’s right—doodling actually changes one’s state of mind. It’s a calming activity that can help people go from a frazzled state to a more focused one. “You can use doodling as a tool ... to change your physical and neurological experience, in that moment,” she says.

If lay people can experience nirvana from doodling, artists who make a living drawing every day must naturally be in heaven. But as the award-winning children’s book illustrator John Hendrix, who wrote the recently published Drawing is Magic, told me, a weird thing happens when artists grow older: “We stop having fun. As a kid you draw without any thought to enjoying it. Enjoying it is assumed! Then we get to art school and learn there is a right way and wrong way to make images. We must all learn how to craft light, space, composition, form, line and shape. But, then after that, we have to be trained to learn to play again.” For Hendrix, finding enjoyment is an essential first step to finding good ideas.

For most people, the big question isn’t “when did you start drawing?” but “when did you stop drawing?” Virtually everyone drew and doodled at one point in their lives. For artists and non-artists alike, drawing is about more than art—it’s about the very art of thinking.