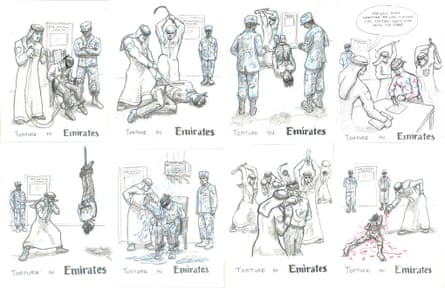

Authorities in the United Arab Emirates have subjected foreign nationals in secret detention to electric shocks, beatings and other abuses, according to evidence shared with the Guardian by multiple sources within the country.

The evidence depicts a variety of brutal techniques employed by UAE interrogators on several foreign nationals, including two Americans, a Canadian and two Libyans, detained since August 2014, most of the time without charge. According to sources in the UAE, each of the prisoners suffered severe beatings, sometimes with rods, sometimes in what was called a “boxing ring”, and sometimes while suspended from a chain.

Other techniques described include electric shocks, prying off fingernails, pouring insects on to the inmates, dousing prisoners with cold water in front of a fan, sleep deprivation for up to 20 days, threats of rape and sexual harassment, and, in two cases, sexual abuse.

The evidence from several sources, shared on condition of anonymity, follows previous claims of torture by family members of the prisoners.

In a statement, the UAE’s embassy in Washington DC did not directly respond to the allegations of torture, but asserted: “The individuals in question are entitled to all of the due process guarantees under the constitution and laws of the United Arab Emirates in accordance with international fair trial standards.”

“During the period of detention they were allowed to contact their lawyers, diplomatic representatives and families,” it continued. Embassy personnel declined further comment “since the case is ongoing”.

The latest allegations echo interviews with detainees’ family members, and separately acquired documents.

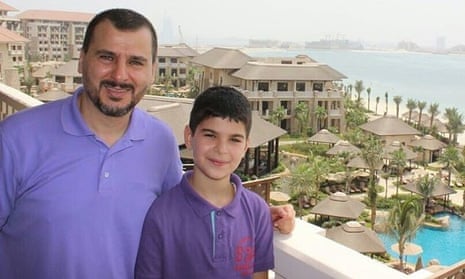

In a report obtained through Canada’s access of information act, for instance, consular officials documented visible injuries on 46-year-old Salim Alaradi, a Canadian-Libyan citizen, when they visited him. The report, from December 2014, details “visible bruises about two inches in diameter on his left arm and leg”.

Alaradi’s brother, Mohamad, was also detained without charge that year but eventually released. Last year he told the Guardian that authorities used “an electric chair”, a “machine” tied to his nails, sleep deprivation and beatings during interrogations.

Similarly, a medical report shared with the Guardian by a former prisoner describes the man’s post-traumatic stress disorder as “caused by his arrest, detention and ill-treatment”. Cornelius Katona, an expert in cases of human rights abuses and the psychologist who evaluated the former prisoner, said that the man’s symptoms are consistent with those of other torture survivors he has treated.

Katona said that the former prisoner told many “incidental details” about the experience that, he felt, enhanced the credibility of the account.

“While he was awaiting deportation he was given terrible food, and while he was being tortured he was given good food,” Katona said. “The torturers wanted to maximize his strength and ability to withstand the torture. These are things I felt he didn’t need to tell me.”

Alaradi appeared alongside two American-Libyan citizens, Kamal and Mohammed Eldarat, in court for the first time on 18 January 2016, and attempted to show the judge the scars during the brief hearing. The judge said his concerns would be heard at a later date. The three men and a Libyan national, Issa al Manna, were charged with supporting terrorism more than a year after their original detention in August 2014.

Earlier this month the UN condemned the trial, citing “credible” evidence of torture and calling for the immediate release of the men involved.

“The suspects have been also allegedly held incommunicado in secret detention locations and in solitary confinement for prolonged periods of time,” said Juan Méndez, the UN special rapporteur on torture.

The UN experts also noted that the men are being tried on a law enacted after their arrest, that they have had limited access to lawyers and their own case files, and that confessions signed during detention may likely be the result of torture.

Nicholas McGeehan, a Human Rights Watch researcher who focuses on Gulf states, said the “fairly large body of evidence is largely consistent in the nature of the detention – the place, length of detention, and the interrogation techniques”.

He said the allegations and documents “point to a state security facility where people are systematically tortured with a view to eliciting confessions”.

In a second hearing on 15 February, the judge unexpectedly ordered a medical evaluation, by a state expert, to examine the prisoners for signs of torture.

“We are very hopeful that my father will be coming home after February 29,” Marwa Alaradi, the prisoner’s 17-year-old daughter said, “but I am also trying to remain realistic and ready for the worst.”

Because the trial is before the UAE’s supreme court, there is no chance for appeal in the event of a conviction. Sentences range from five years in prison to a life term or execution.

Arif Lalani, Canada’s ambassador to the UAE, attended both of the hearings held so far for the four foreign nationals, according to Tania Assaly, a spokeswoman for the Canadian foreign ministry.

The Canadian government has urged the UAE “to ensure that Mr Alaradi receives a fair and transparent trial in accordance with due process,” she said. “Officials at very high levels”, she added, have raised “our concerns regarding Mr Salim Alaradi’s health, wellbeing and consular access”.

“Canada takes allegations of mistreatment and torture extremely seriously,” Assaly said, and added that the government is working “to ensure a prompt and just resolution”.

Mark Toner, deputy spokesman for the US Department of State, sent a similar statement to the Guardian, but did not say whether the American ambassador, Barbara Leaf, had attended the hearings with US embassy personnel.

“We have raised these allegations [of torture] with senior leaders of the UAE government,” Toner said, “and have requested that local authorities provide them access to medical care and appropriate treatment while in prison.”

According to research by the human rights group Reprieve, 75% of prisoners in Dubai’s central prison claim to have been tortured, including with beatings, electrocution and threats of rape. This week Human Rights Watch released a statement from Mosaab Ahmed Abd el Aziz, an Egyptian held in the UAE, who similarly accused authorities of torture.

Abd el Aziz told the rights group he would have confessed “to coming from Mars to destroy Earth” simply “to get it over with”.

The Eldarats and Alaradi, all of whom either dual Libyan citizenship and roots in western Libya, argue that the detentions and trials are politically motivated.

“This goes back to 2012,” McGeehan said, “with the arrest of Emirati dissidents. This entire crackdown is rooted in Abu Dhabi’s fear of reform and these guys are the latest victims of that.”

Since revolutions erupted around the Middle East in 2011, including the one that toppled Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi that year, the UAE and other Gulf states have cracked down on internal dissent and intervened abroad. In 2014, the UAE and Egypt also launched airstrikes in Libya in support of eastern factions, and last year the UAE joined Saudi Arabia with strikes in Yemen.

The Alaradis and Eldarats maintain their relatives’ innocence to the charges of having provided material support to terrorist groups in Libya.