My Kashmir newspaper has been shut down, and I’m not surprised

- Published

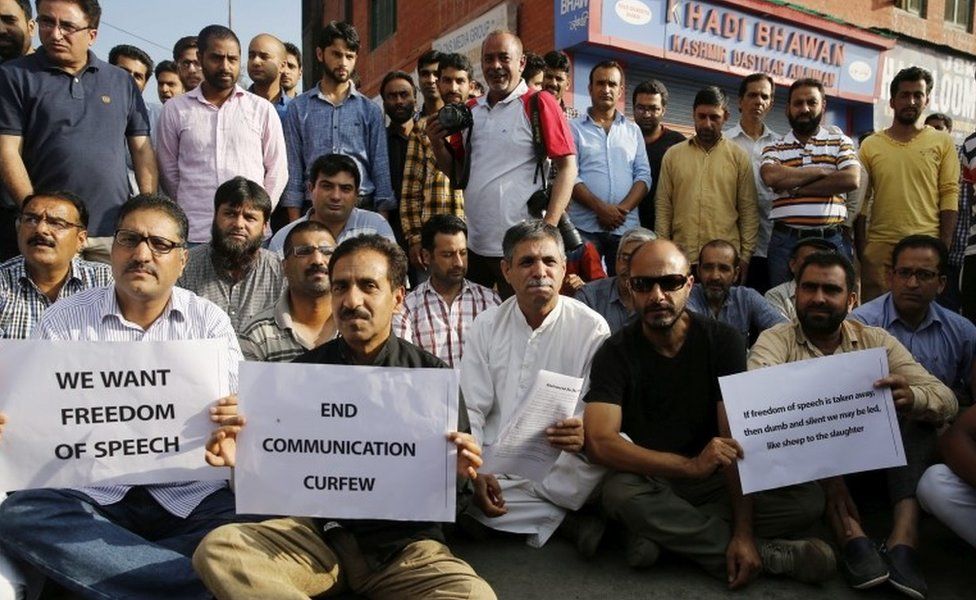

Authorities have shut down newspapers in Indian-administered Kashmir seeking to end violent protests sparked by the killing of a prominent separatist militant. Shujaat Bukhari, editor of the Rising Kashmir, writes on why the news blackout does not surprise him.

A friend called me on Saturday morning and was anxious to know whether all was well with our newspaper.

"Has your printing press also been raided?" he asked.

I told him I would have to check. He said other newspapers were updating their websites saying their presses had been raided.

I thought hard about whether we had published anything "inflammatory" after the protests began, but could think of nothing.

Not shocking

But when I called the office, one of our employees confirmed that that our printing press had been raided, staff held and printed copies of the newspaper seized.

I was not surprised.

When Afzal Guru, a Kashmiri separatist convicted over the 2001 Indian parliament attack was hanged in 2013, copies of newspapers were seized from the press and the stands. I remember my newspaper ceased publication for four days. During the 2010 agitation, we were forced to stop publishing for 10 days.

This time more than 40 people have already been killed in violence after the killing of a prominent militant, Burhan Wani. More than 1,800 others have been injured. A curfew remains in place - along with curbs on mobile and internet access.

Imposing an information blockade had been part of the state "strategy" in 2010 as well and the scene is rewinding this time.

Mobile phone services - including data - except that of a government owned service provider have been barred, cable TV is the off the air and some 70 newspapers - in English, Urdu and Kashmiri languages - have officially been asked to stop publication for a few days.

Only a handful of broadband connections are helping us keep in touch with the rest of the world.

Not new

For us these restrictions are not new.

Since the outbreak of armed rebellion in Kashmir in early 1990, media in the region has had to work on a razor's edge in what is effectively the world's most heavily militarised zone.

Thirteen journalists have been killed during the conflict since 1990. Threats to life, intimidation, assault, arrest and censorship have been part of the life of a typical local journalist.

Journalists have been targeted by security forces and militants alike. Publications have been denied federal government adverts -a key source of revenue for smaller newspapers.

If a local journalist reports an atrocity by the security forces, he risks being dubbed "anti-national". Highlighting any wrong doing by the militants or separatists could easily mean that he is "anti-tehreek" (anti-movement) or a "collaborator".

Kashmir's Education Minister Naeem Akhtar has said the media ban was "reluctant decision".

"It is a temporary measure to address an extraordinary situation… In our opinion, there is an emotional lot, very young, out in the field, who get surcharged due to certain projections in the media, which results in multiplication of tragedies," he told The Indian Express newspaper.

By banning newspapers, a government that is desperately grappling to normalise the situation, has opened up space for rumour mills to flourish that could aggravate the already surcharged atmosphere.

Media should not be seen as an enemy in a democratic set up. Stifling the media does not help to strengthen the democracy that has been under threat in Kashmir for such a long time.

- Published27 March 2006

- Published14 July 2016

- Published11 July 2016

- Published11 July 2016

- Published8 April 2016