On a 100-degree day this past July, Edward Poindexter woke at 8:30 a.m., as he does most mornings, and walked for an hour around the 400-meter track in the west yard of the Nebraska State Penitentiary in Lincoln. If you walk alongside the fence enclosing the yard on Monday, Thursday, or Saturday mornings — moving quickly so you won’t be noticed by the guard in the closest security tower — you might catch a glimpse of Poindexter: big, bald-headed, propelling himself forward in figure eights, a cane in each hand. A fixture here, he is sometimes joined by young gangbangers seeking advice.

As a reserved, introspective child growing up in the early 1950s in Omaha’s predominantly black Near North Side, Poindexter’s favorite activity come summertime was to walk, alone, to an open field on the outskirts of the ghetto. Once there, he’d gorge himself on mulberries and admire the nice homes around a nearby elementary school in the white part of town. The first time he found the field he was stunned. Up to that point his entire world was eight or nine blocks. Omaha, he realized, was a big and varied place.

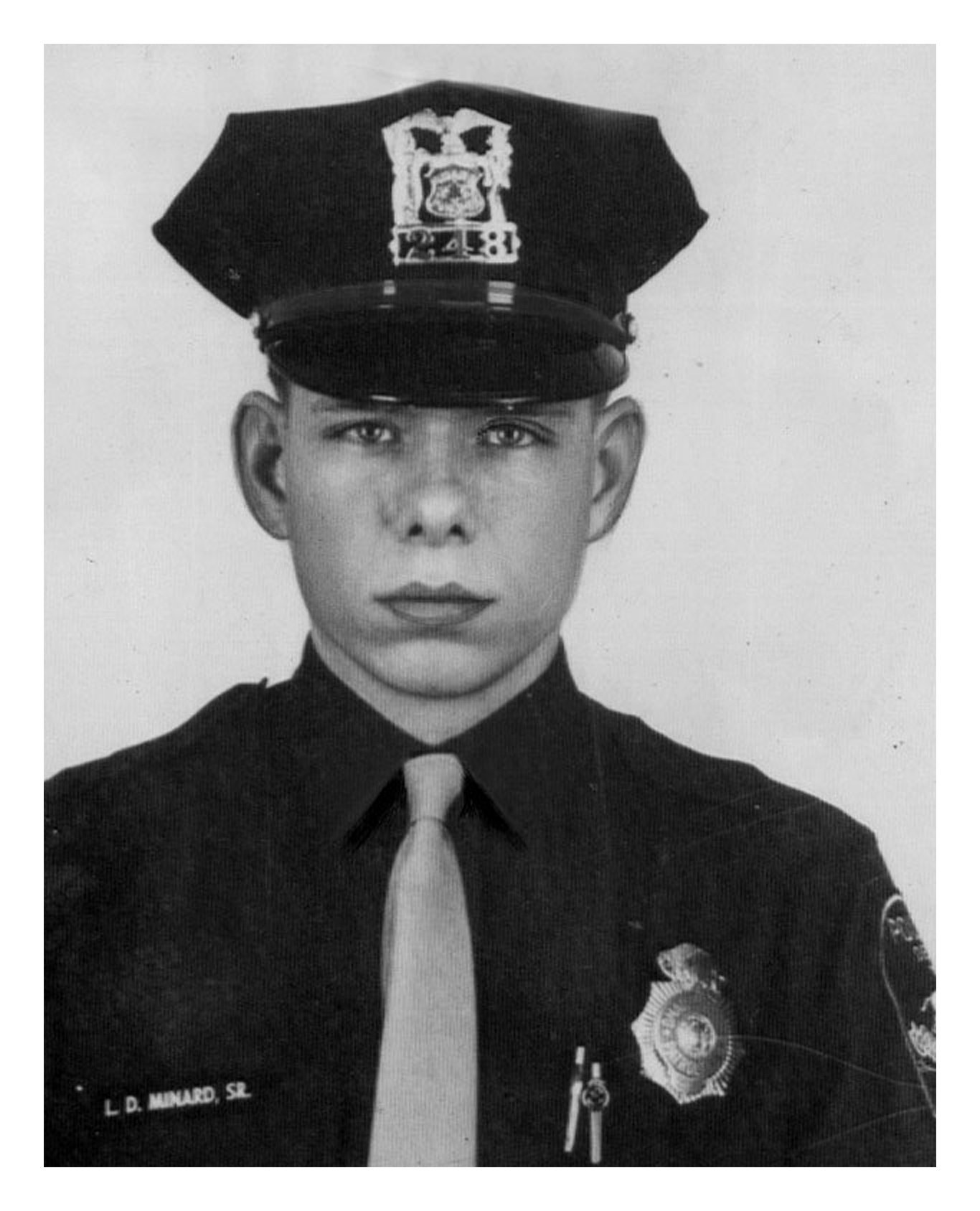

In some ways, 71-year-old Poindexter is more like his childhood self than the hotheaded man he was in April 1971 when he — along with David Rice, now known as Wopashitwe Mondo Eyen we Langa — was tried, convicted, and sentenced to life in prison for the murder of Omaha policeman Larry D. Minard. Minard died when a suitcase bomb exploded in a North Omaha home on August 17, 1970 — one of a series of bombings to shake the Midwest that spring and summer. He was responding to a phony report that a woman had been dragged, screaming, into the vacant home.

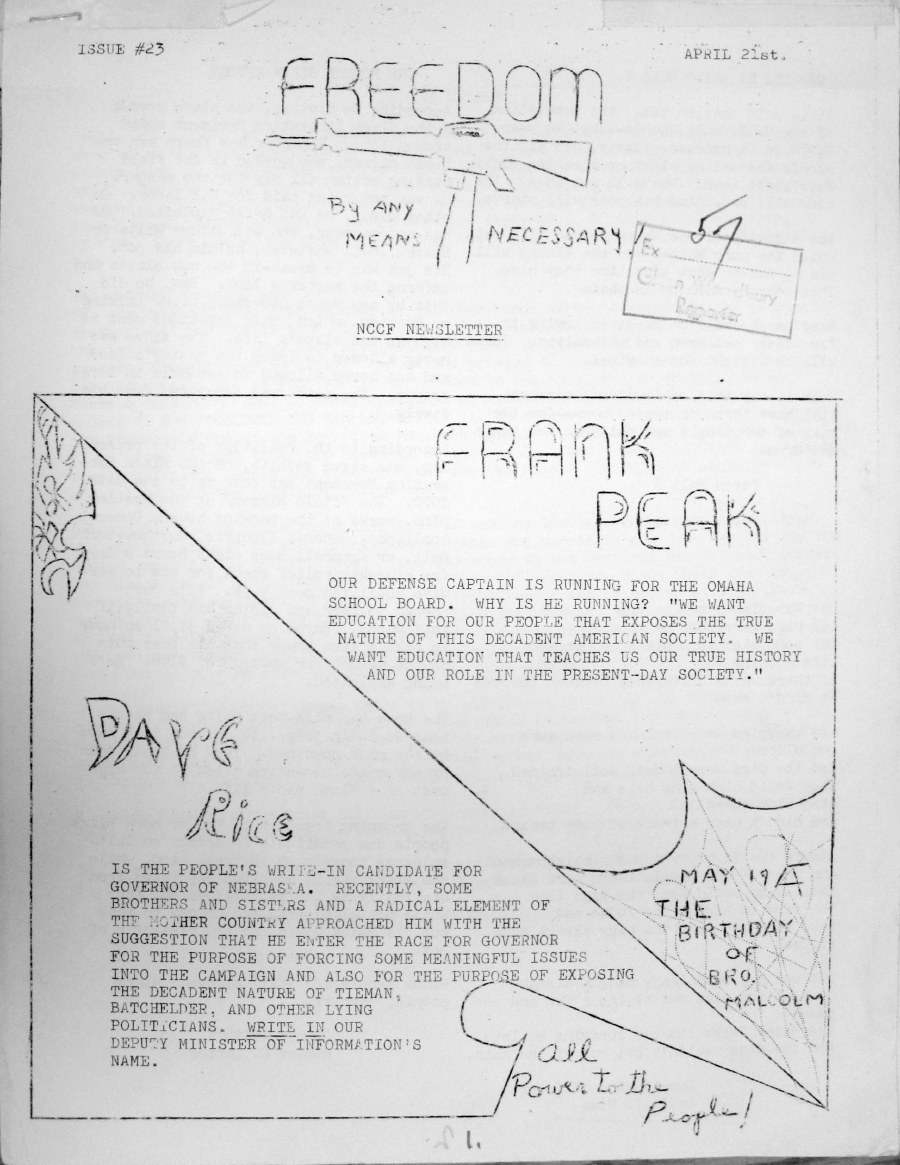

At the time, Poindexter and we Langa were leaders in Omaha’s National Committee to Combat Fascism (NCCF), the successor to the recently dissolved Omaha chapter of the Black Panther Party. The two were arrested after Duane Peak, a 15-year-old former NCCF member, implicated Poindexter and we Langa as the brains behind the bomb plot, though he initially confessed to planting the bomb and placing the phony 911 call alone. By the time their trial was over, Peak would again change his testimony, Poindexter's and we Langa’s alibis would check out, and the two men’s hands would test negative for the dynamite residue found on their clothes. Key evidence would be withheld from the defense. The jury — of which 11 of the 12 members were white — found them guilty.

Since then, we Langa and Poindexter’s case has penetrated every level of the criminal justice system, from local officials to former governors to the FBI to the Supreme Court. It’s been mired in suspicions of murky police practices, backroom plea deals, allegedly planted and suppressed evidence, and a teenage suspect whose testimony may have been coerced.

It’s a story Poindexter has told so often it’s almost become routine for him, although there’s nothing routine about what he has to say, about the pain of lost decades or the prospect of dying in prison for a crime he insists he and we Langa, who is now 68 and incarcerated in the same prison, didn’t commit. Like those of better-known revolutionaries such as Mumia Abu-Jamal and Geronimo Pratt, Poindexter and we Langa’s story is part of the tangled history of the ’60s and ’70s. Hovering in the background is former FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, who ordered agents to neutralize the Black Panther Party across the country. It’s a story that few people know and both men are running out of time to tell.

If innocent, we Langa and Poindexter are among the longest-serving political prisoners in the U.S.

Though Amnesty International has called for we Langa and Poindexter to have a new trial or be released, their case has received little national attention. Omaha, too, has mostly forgotten them, forgotten that the Panther story extends beyond Oakland and Chicago. At the same time, the issue that prompted the formation of the Omaha chapter of the Black Panther Party — police brutality — is very much alive and in the national consciousness.

Today, 50 years after the party’s founding in 1966, Poindexter and we Langa are two of 20 former Black Panthers currently in prison across the United States. As of last August, the men, dubbed the “Omaha Two,” have been in jail for 45 years. If innocent, they are among the longest-serving political prisoners in the U.S.

The night was unreasonably humid, typical of Omaha in August, and Officer Larry D. Minard — on cruiser duty with his rookie partner — looked forward to the end of his Monday night shift. A few days shy of 30, Minard was a slight man with boyish features, already a father of five and a seven-year-veteran on the force.

A little over two hours into his shift, Minard overheard an emergency message: A woman was being assaulted at an address — either 2866 or 2867 Ohio St. — in the heart of the city's Near North Side. Another cruiser had been assigned to the call. Minard went anyway.

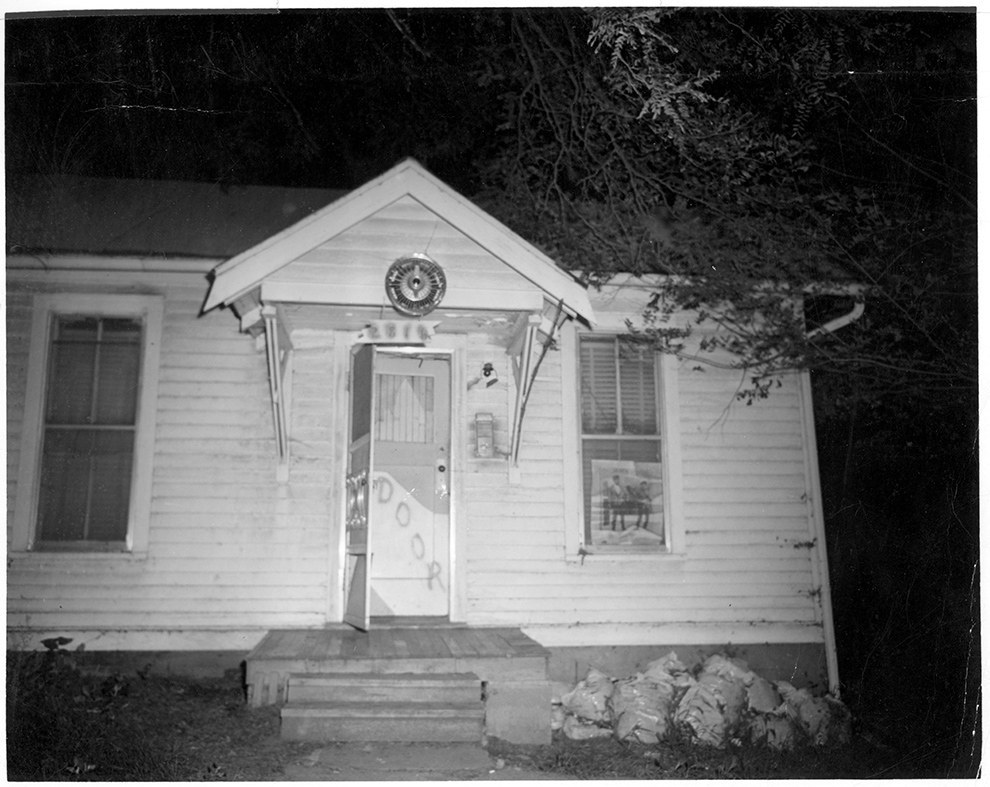

Minard and his partner were the first on the scene, stopping in front of 2867 Ohio just after 2 a.m. He and four other officers, including John Tess, a 22-year-old, sandy-haired policeman who’d been on the force for a little under a year and a half, made their way inside the house. Single-file, they stepped quickly through the foyer, each circumventing a gray Samsonite suitcase placed just inside the front door.

Minard and Tess secured the bedroom. Finding nothing, they started back toward the front door, with Tess following Minard several feet behind. At that point Minard returned to the suitcase and, possibly kicking or tripping over it, triggered an explosion so powerful it knocked over a curious neighbor watching from across the street.

Initially, John Toay — one of the eight total officers who eventually responded to the 911 call — thought the bare leg poking through the rubble belonged to the woman they’d been searching for. He was the first to respond to Tess’s cries for help. “I couldn’t see, the smoke and dirt and debris was about knee-high… I got on my hands and knees and crawled down through a hallway,” Toay later testified. He found Tess pinned down by plywood. Tess gestured toward a form in the darkness a few feet away. It took Toay a moment to register the shape as a limb, and another to recognize it as Minard’s, the fabric of the young father’s pant leg mostly burned away. It was then 2:11 a.m. By 3:15, police officers and firefighters had covered Larry Minard with a heavy canvas.

By the time rescue personnel removed Minard’s body from the wreckage, a light rain was falling and Edward Poindexter, the handsome and towering 26-year-old leader of the Omaha NCCF, was taking a hot bath in his mother’s apartment, a few blocks away from the blast site.

The evening had started out well enough. He and his date caught a showing of Cotton Comes to Harlem, an Ossie Davis blaxploitation film that had become an unexpected commercial hit. It was only Poindexter’s second time at the Orpheum in downtown Omaha, and he marveled at the change in clientele since his first ill-fated outing at the historic theater. A recently returned army veteran, Poindexter had come a long way from the clean-cut, gangly teenager who was once spat on by white kids seated above him in the Orpheum’s balcony seats. Hardened after six years of service, Poindexter returned from Vietnam angry over missed promotions stemming from what he suspected was racism. The NCCF’s commitment to racial and social justice gave him an outlet to channel his frustration.

After the movie, the young couple took the bus back into the heart of the Near North Side. Poindexter walked his date the rest of the way home, where they talked on her porch for an hour before he decided to head out. Enjoying the summer air, he decided to risk walking the mile to NCCF headquarters at North 24th Street, keeping his eye out for cops eager to find excuses to pick up a Panther. Poindexter was about a half block into his walk down Lake when he heard the loud boom, felt the pavement shake beneath his feet, and saw an old house rattle.

Later, in the bath, Poindexter prayed that none of the party members had anything to do with the explosion. He would have to wait for the morning news to find out precisely what had happened. Dawn was three hours away. He sank deeper into the hot water and felt the knot in his stomach slowly loosen. None of the local Panthers, he told himself, were stupid enough to set off a bomb in their own backyard. In bed minutes later, he pulled the sheets over his head and closed his eyes against the dark.

By 4 a.m. Edward Poindexter had drifted into a deep sleep, but across town in midtown Omaha, David Rice, a 22-year old NCCF member and self-described “blippy” — black hippy — stirred into wakefulness. He had stayed up late drinking wine and listening to records before falling asleep next to his white girlfriend, Katie, on a friend's living room floor. But the radio had jolted them awake. The report — that a house had been bombed and a policeman hurt — left him uneasy. He went back to sleep for another hour, but finally gave up and decided to head home.

The morning was balmy, but at 5 feet 8 inches and 146 pounds, Rice got cold easily. He shivered a little as he waited outside for his brother to give him a ride home. On hot summer days he liked to close the windows in his tiny house and turn the heat all the way up. His friends ribbed him for the unusual habit. For the most part, though, they were used to Rice’s eccentricities. A performance artist, poet, and former Catholic-school kid, Rice wasn’t the traditional Panther recruit. Still, his eloquence and outlandish sense of humor had won him the respect and affection of Panthers both in Omaha and from other towns. He was flattered when he was asked to give a talk to raise money for fellow Panther Pete O’Neal’s defense fund. The chair of the Kansas City chapter, O’Neal had been arrested for transporting a shotgun across state lines as a former felon — an infraction that had become law just two weeks earlier. Rice planned on heading to Kansas City on Friday. He was optimistic that O’Neal could beat the gun charge — perhaps, his friends thought, overly so. (O’Neal was eventually sentenced to four years in prison and fled to Tanzania, where he still lives today.) But that was Dave. Always looking on the bright side.

Once home Rice blasted the heat and rummaged through his record collection before deciding on Coltrane. The walls of his front room were painted black, the ceiling spray-painted with silver and gold Aztec designs, stars, moons, and lightning bolts. He’d made a strobe light out of empty beer bottles, wire, lightbulbs, and wood salvaged from dumpsters and construction sites. He called the room the “Room of Darkness,” and many weekends he danced under its makeshift sky.

Rice collapsed onto his couch. His mattress was in the adjacent room (“The Room of Many Colors,” streaked with blue, yellow, and pink triangles), but he was too tired to leave the sofa and lay instead on his back, staring up at his metallic ceiling. He pushed the bombing out of mind, and settled in for another hour of sleep.

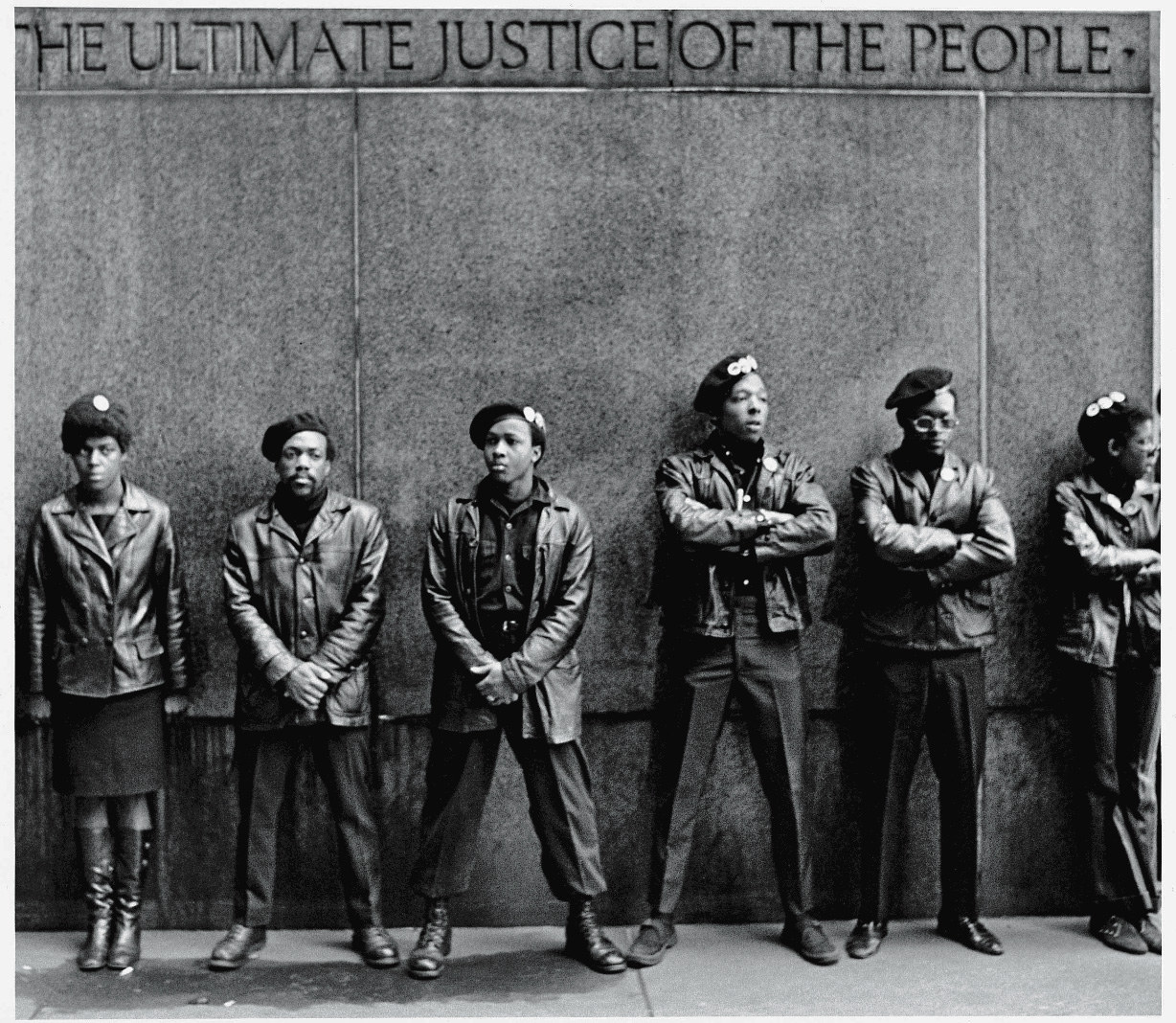

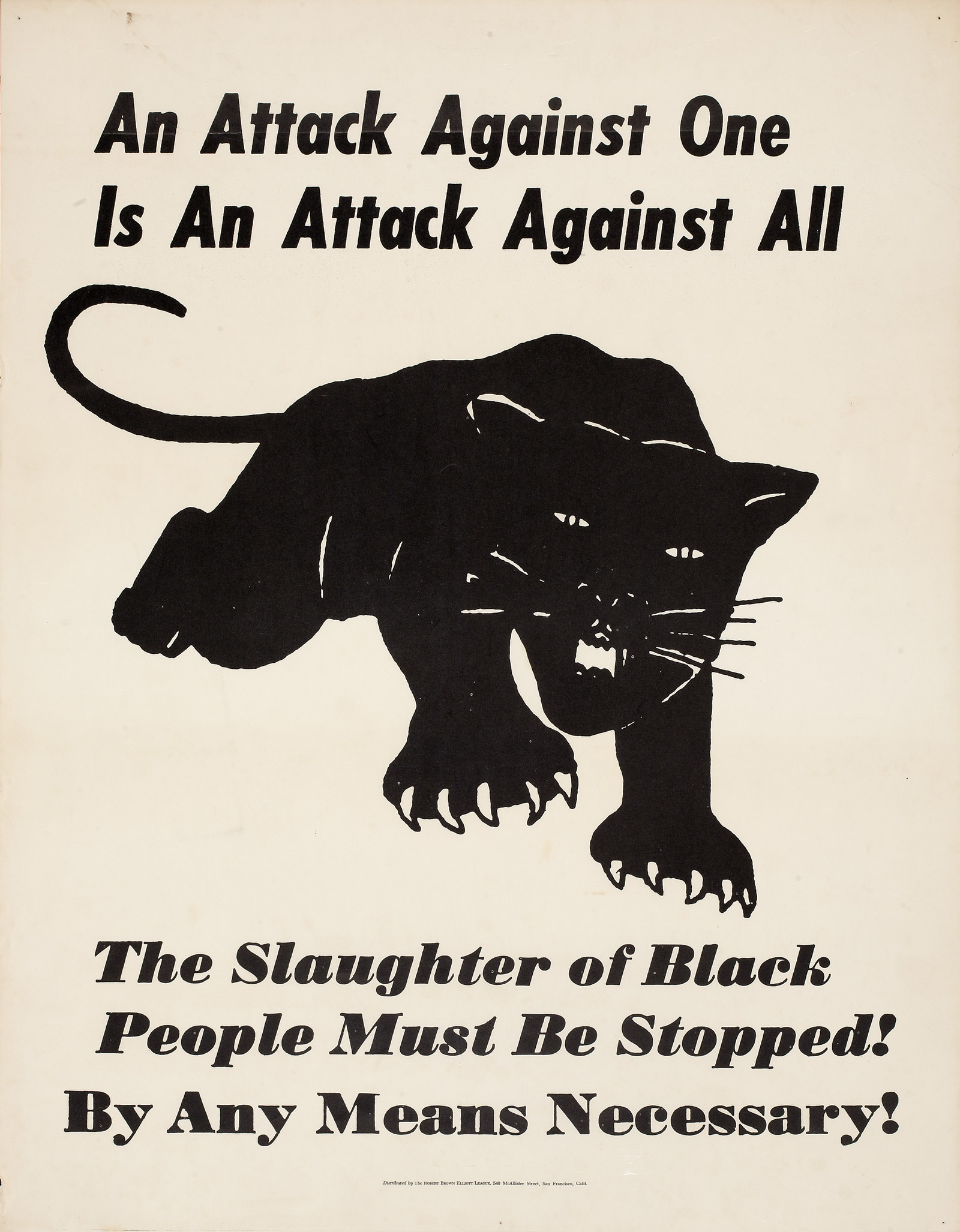

In the late 1960s, thousands of young black people joined the Black Panther Party and devoted their lives to the revolutionary struggle. By 1970, polls suggested that almost two-thirds of the black communities in major cities approved of them. The movement, with its dramatic revolutionary rhetoric, endorsement of armed self-defense, and open defiance of white authority, was a marked contrast from much of the reformist anti-segregation activism of the civil rights era. It instilled a sense of racial pride and self-esteem in young black Americans across the country.

For white Americans outside of the New Left and hippie counterculture, however, the Panthers embodied their worst fears. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover repeatedly referred to the Panthers as the “greatest threat to the internal security of the country.” Accordingly, the Black Panthers quickly became the focus of the FBI’s secret Counterintelligence Program (Cointelpro), which was used to undermine the popular mass movements for social justice of the ’60s and ’70s. Cointelpro tactics went beyond surveillance; the bureau secretly used fraud and force to disrupt constitutionally protected political activity and manipulated criminal prosecutions throughout the country by withholding exculpatory evidence and arranging false testimony.

Though founded in 1968, the Omaha chapter of the BPP gained much of its support after June 1969, when local police shot Vivian Strong, an unarmed 14-year-old black girl who was one of three black teenagers killed by police in Omaha that year. In the aftermath of Strong’s death, local Panthers mobilized, working hard to increase the party’s visibility in the community. Emulating Panther chapters elsewhere, they established free breakfast programs, a community newsletter, and armed patrols of the police in which members would document police behavior and show up at scenes of cop harassment with their guns in plain view. Poindexter and Rice were part of this push, and both men organized and taught classes in political education for black youth at the newly opened Vivian Strong Liberation School.

The party fell out of favor with Panther leadership in Oakland at the height of its efficacy, however, after anonymous letters disparaging Rice and Poindexter were received at national headquarters. One letter accused Rice of “reluctance to follow the party line” by accepting employment from a government-funded agency (he worked at an anti-poverty program called Greater Community Action). Another accused Poindexter of mishandling party funds. As a result, the chapter disbanded in August 1969, but reformed as the National Committee to Combat Fascism (NCCF). It was for all intents and purposes the same organization. Years later, Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests would reveal that a targeted smear campaign of anonymous calls and letters was being conducted at the time against the BPP by the Omaha FBI.

In the three months leading up to Minard’s murder, police departments in Omaha, Des Moines, and Ames, Iowa, had been on high alert over missing dynamite. In mid-May, bombs exploded at the Des Moines police station and chamber of commerce — the first in a rash of nonfatal bombings that subsequently shook the three sleepy Midwestern cities, most of which remain unsolved. Police wondered briefly if the bombings were the work of anti-war radicals. But in the weeks before Minard’s death, their suspicions had fallen on the NCCF.

“Isn’t that something? They call us to help somebody, and the building blows up.”

Hatred of the police, Minard’s colleagues lamented, had become a national syndrome. “We go in there to help somebody, and they kill us,” Toay told the Omaha World-Herald the morning following the bombing, referring ostensibly to residents of the black neighborhoods in the northern and northeastern parts of the city where the bombing had occurred. “Isn’t that something? They call us to help somebody, and the building blows up.”

In the hours after Minard’s death, angry deputy sheriffs, state troopers, and federal investigators convened for a special meeting of Domino, a group formed to foster interagency cooperation. “Preliminary discussion was brief and pointed,” wrote James Moore, an agent from the Alcohol Tobacco and Firearms (ATF) Division in his 1997 book Very Special Agents. “The weapon, the method and the target suggested extremists. Panthers and Weathermen murdered policemen this way. The Negro voice on the dispatcher’s tape suggested Panthers.”

Two days after Minard’s funeral — and despite the systematic questioning of hundreds of members of Omaha’s black community — police still had no idea who had placed the fake 911 call or planted the bomb that killed Minard. Dozens of work hours had been wasted on false leads. Then, a tip from an unnamed informant sent officers into a North Omaha housing project early in the morning of August 22 to pick up an 18-year-old named Annie Lee Norris.

Annie Lee wasn’t a likely suspect. Her mother, Olivia, worked as a babysitter, and their small apartment was often bustling with children, hardly an environment suited to storing dynamite. Still, acting on a rumor that the Norris family knew something about the murder, detectives searched the apartment for explosives before taking Annie Lee to the station for questioning.

The teenager, terrified, told police she’d been up late playing cards when she heard the explosion. But by the time the interrogation was over — she would remain at the station until 3:30 in the morning — Annie Lee would be the first to connect a local Panther to the Minard slaying.

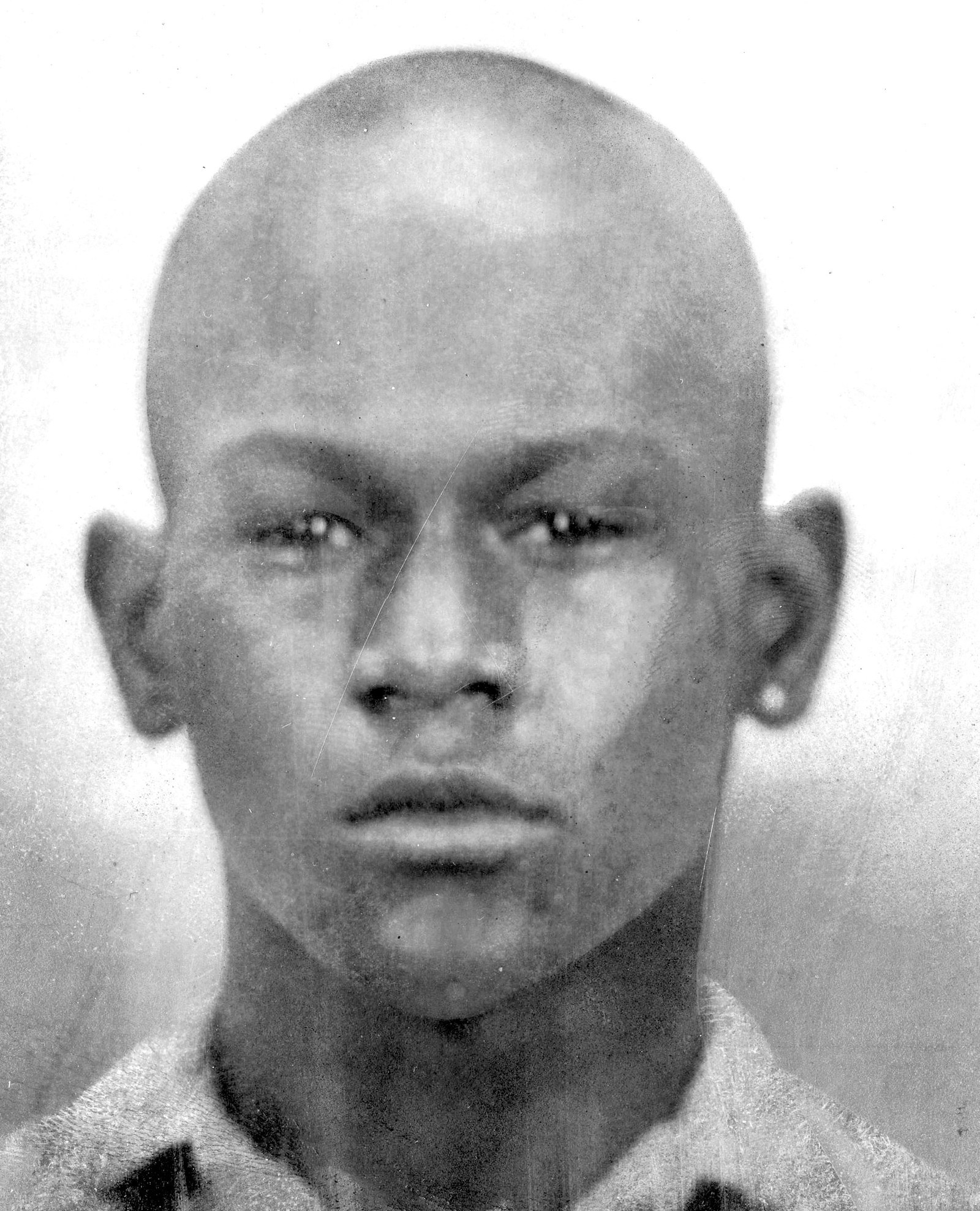

On the night in question, Annie Lee told investigators, she had been idling at home when a neighborhood pal, 15-year-old Duane Peak, stopped by for a visit. A slight kid who looked more at home on a schoolyard than going toe-to-toe with police officers, Duane nevertheless had a reputation for being wild. When he was 14, Duane stole a police riot gun and took it to NCCF headquarters. Not long afterward, neighbors of Annie Lee told police he and another boy had set a shack on fire behind a gas station. A Panther wannabe, Duane had been eager to join the NCCF. His cousins, Frank and Will, were members and close friends with Poindexter. Sometimes they let Duane hang around headquarters, where he would answer the phone or watch Will Peak’s kids. But even these tasks proved too much for Duane, who often came to headquarters high and half alert. According to Poindexter, the final straw came when Duane shot up headquarters while trying to kill a sparrow that had flown into the building. Poindexter kicked him out, telling Frank and Will to keep their cousin away. Sometimes, Annie Lee recalled, she would find Duane sitting out back taking drugs and boasting to other boys of his brief stint with the NCCF.

Still, Annie Lee knew that beneath the bravado Duane was a vulnerable kid, still hurting from his mother’s unexpected death from lung cancer three years earlier. Since then, he and his 20-year-old brother, Donald, were often in and out of the house. Duane, in particular, looked upon Annie Lee’s mother as his own. A high school dropout with nowhere to stay, he bounced from place to place, the few clothes he owned slung over his shoulder.

According to court records, when Duane turned up at Annie Lee’s house on the 16th, he was carrying a light gray Samsonite suitcase. He was planning on joining the Job Corps, he explained, and needed to stop by for some clothes. Nothing struck Annie Lee as unusual about the bag. When she reached for it, however, Duane warned her not to touch it, saying he had drugs inside. A few minutes later, Donald Peak burst in. The two brothers took the suitcase into the kitchen. Annie Lee could hear them laughing from the other room. A woman came by to pick up her kids. The brothers caught a ride. Annie Lee didn’t know where to. On their way out Duane asked her for the police emergency number. She shrugged: "9-1-1."

The next time she saw Duane and Donald was Monday night, following the bombing. The younger children were playing outside, Olivia Norris had stepped out for a moment, and briefly, Annie Lee recalled, she and Duane Peak were alone together and sat on the couch, chatting. Donald appeared at the front window, startling them. He ribbed his little brother: “What’s the matter, old boy, can’t you sleep? Don’t let it bother you.”

More damning was Annie Lee’s revelation that toward the end of the visit she'd overheard her mother teasing Duane and Donald at the door. “How come you boys blew that policeman up?” joked Olivia Norris. Duane quipped: “The next time a dumb cop sees a suitcase in the middle of the floor he isn’t going to go over and pick it up.”

At one point during her interrogation, Annie Lee was escorted to the sixth floor communications room, where the phony 911 call was played for her repeatedly. At first Annie Lee identified the voice on the recording as Duane’s. After the second or third time listening, she switched brothers.

The following morning, Donald Peak was arrested and taken to the station in handcuffs. Two of Duane Peak’s sisters, their boyfriends, and a neighbor told police that they had also seen Duane carrying a suitcase in and around the projects on the evening in question. Both sisters admitted to giving Duane a ride at different times that Sunday, with the older of the two dropping off Duane — his suitcase in tow — in an alley between Lake and Ohio streets around 10:30 p.m. Donald initially told police that he had seen his little brother remove clothes from the suitcase. But about two-thirds through the interview, he began asking some questions of his own: What could happen to a person, he wanted to know, who knew about the bombing, but wasn’t involved? Duane, Donald eventually admitted, had told him he was carrying the suitcase “for the party.” His kid brother couldn’t possibly have acted alone. Edward Poindexter, Donald offered, had military training. He was the only member of the NCCF who might be capable of assembling a bomb. The next day, Poindexter was arrested on suspicion of conspiracy to commit murder.

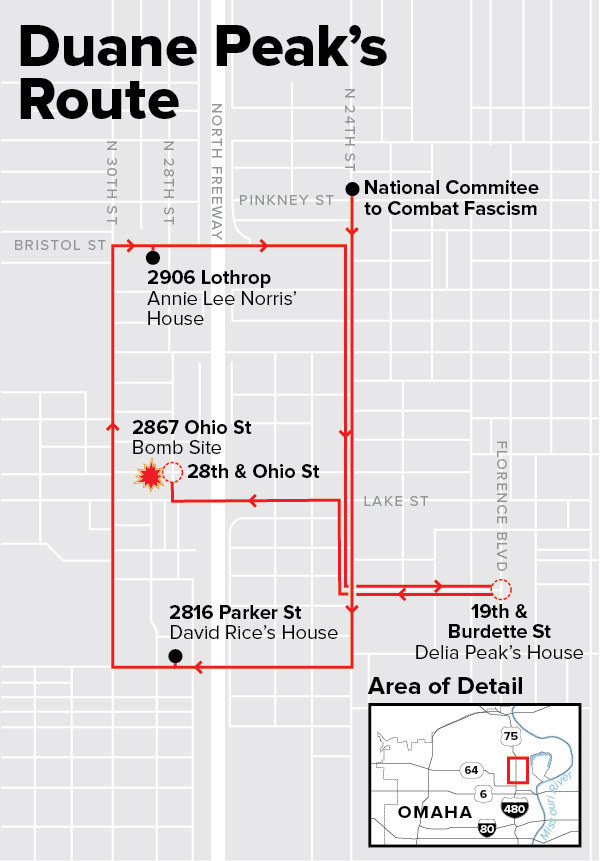

Duane Peak managed to evade capture for almost a week. Then, early in the morning on August 28, he was apprehended while asleep on the front porch of a friend’s home in North Omaha. At the station, without an attorney present, he told police that he got an anonymous note at the NCCF headquarters on August 16 instructing him to pick up a suitcase in an alley behind the Lothrop Drug Store and take it to a vacant lot at 28th and Ohio at 10 p.m. The note instructed him to be at a pay phone at 2 a.m. The phone rang and a female voice he did not recognize told him to call 911 and report that a woman had been dragged into a vacant house at 2866 or 2867 Ohio. Three days later, on August 31, after several meetings with police over the weekend, Duane changed his story, telling County Prosecutor Art O’Leary that the plot was the brainchild of NCCF leaders Ed Poindexter and David Rice.

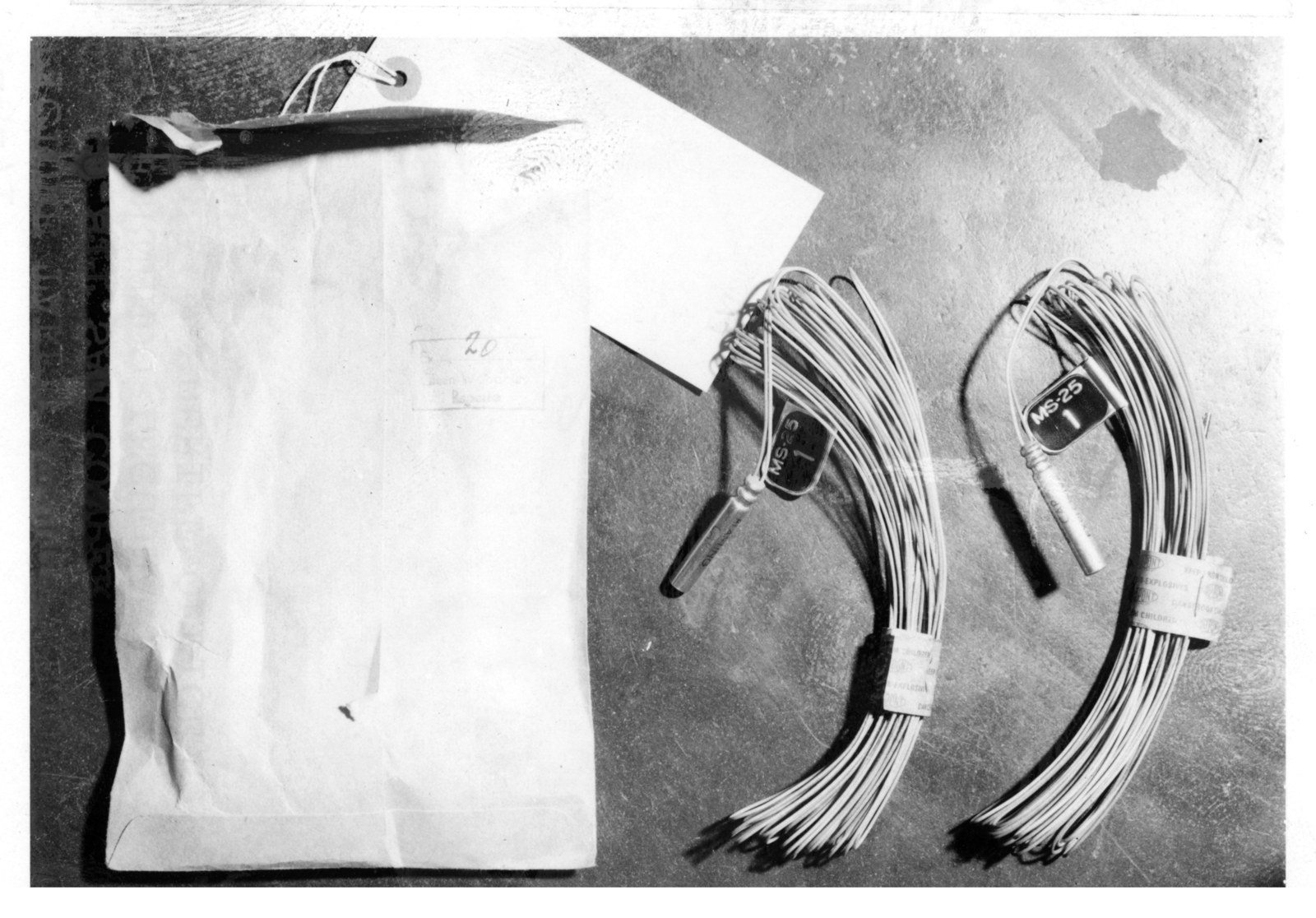

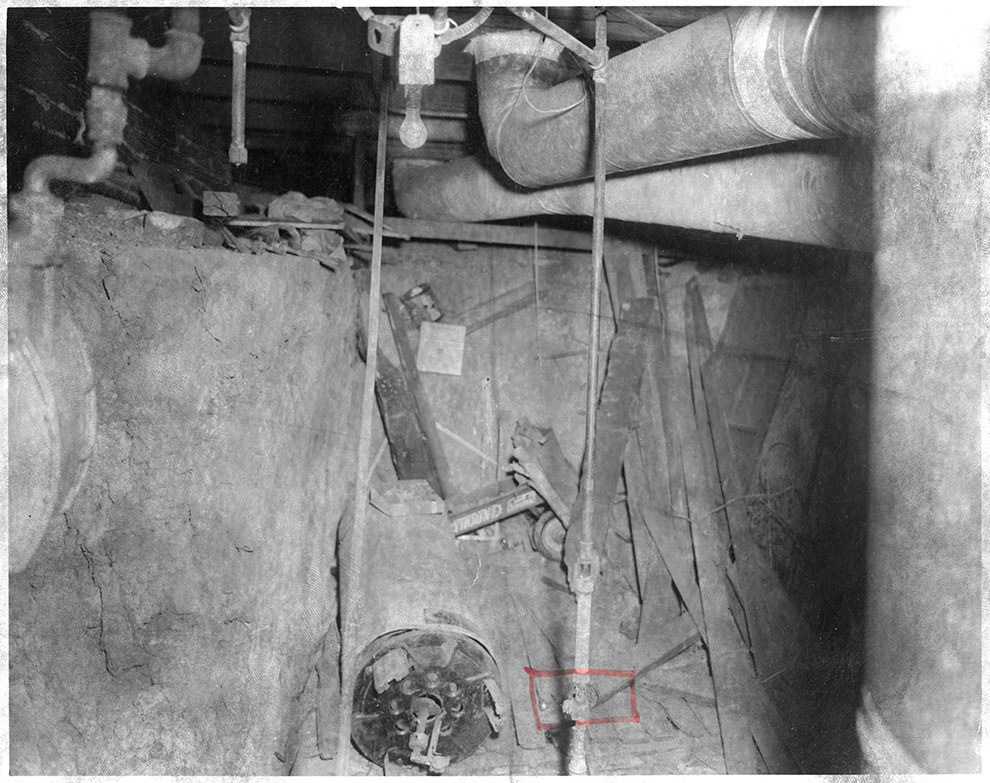

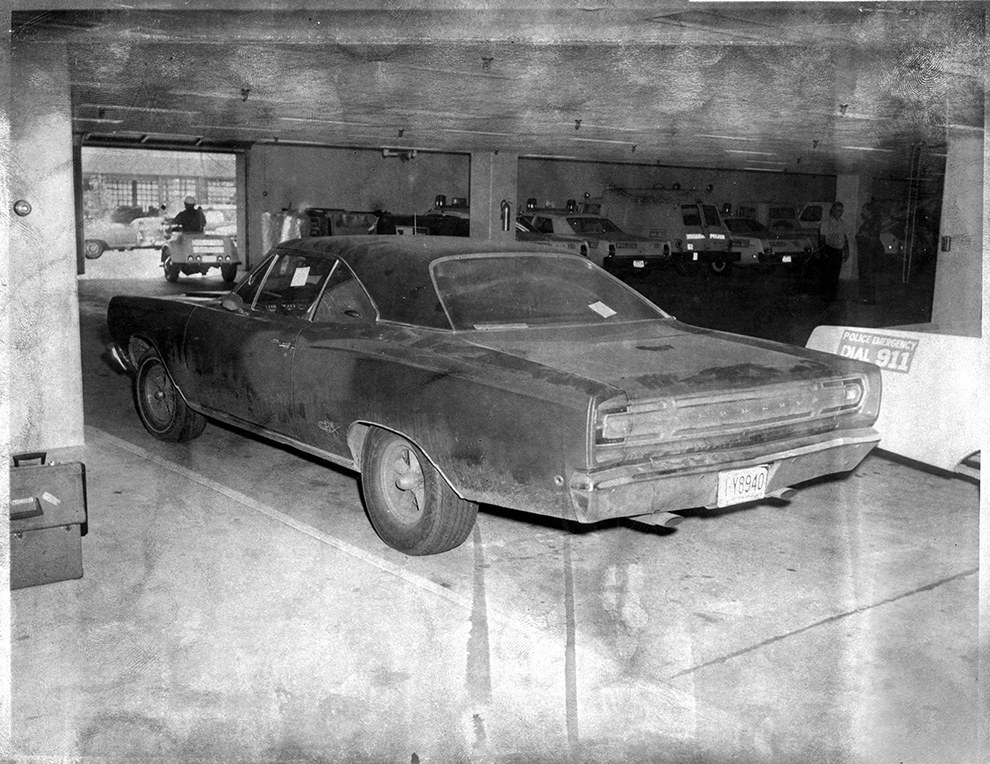

Rice’s home had been among the locations where detectives suspected Duane might be hiding. While Duane was on the run, police searched Rice’s home on August 22 and recovered from his basement and living room 14 sticks of Dupont Red Cross 50% strength dynamite, a Marathon 6-volt battery, four blasting caps, and a pair of pliers. Duane’s latest story linked the dynamite in Rice’s home to Minard’s murder.

The new story began on August 10, seven days before the explosion. Duane was hanging out at NCCF headquarters when Poindexter took him aside. “He said he was going to make a bomb,” Duane told police. They caught a ride to David Rice’s house. There, Duane said, Poindexter brought dynamite up from Rice’s basement. Rice provided the suitcase from his bedroom. Duane watched as Poindexter made the bomb in Rice’s kitchen using three sticks of dynamite and a battery taken from a flashing street sign.

The next day, a Tuesday, Duane met Poindexter at his cousin Frank’s home. From there they walked to Ohio Street “to go and look at a vacant house up there.” Duane said the next time he saw Poindexter was on Friday night, the 14th, at the American Legion where Duane was performing with a singing group. There, they discussed Duane’s role in the bomb plot. Poindexter asked Duane why he hadn’t taken the suitcase to 2867, but Duane said he did not want to be involved and was afraid of messing up. “Something is going to happen to you,” Duane said Poindexter told him in his deposition, if he didn’t follow orders. He did not see Poindexter again.

On Sunday afternoon, Duane caught a ride from headquarters to David Rice’s house from a white girl who was dating one of the NCCF members. When he got there Rice handed him the suitcase. From there the white girl gave him a ride to Annie Lee’s house, where he stayed and chatted with Annie Lee for 20 minutes before Donald Peak, who was drunk at the time, dropped in. Their sister, Theresa, gave the brothers a ride to their other sister Delia’s house, where they stayed for hours, visiting and watching TV. Around 10:30, Delia, her boyfriend, two of her young kids, and two friends decided to go to the store. She asked Duane if he needed a ride anywhere and dropped him off at 28th Avenue, between Ohio and Lake. From there he walked to 2867 Ohio and waited on the porch for an hour before placing the case in the middle of the living room around midnight.

Shortly thereafter, Duane walked to the projects and got a ride back to Delia’s. Around 1 a.m., he walked to a phone booth near Delia’s house and called 911.

When O’Leary asked Duane if he knew how the bomb was triggered, Duane shrugged: “I guess it must have been from the wire that extended from the bottom of the suitcase.” He hadn’t, he insisted, attached the blue wire to the floor, which would have armed the bomb to explode. He also had no idea who moved the case from the living room to the doorway in the two hours before he placed the phony call. “Find out,” O’Leary wrote later in a trial memorandum, “if a mere jarring of the suitcase could trigger the device if the blue wire was not attached. For instance, could a party who kicked the suitcase trip the device and trigger the blue wire? (Make your expert say that is possible).”

On a clear September morning less than a month later, Duane approached the witness stand in a third-floor courtroom in the Douglas County Courthouse in downtown Omaha. The daylong joint preliminary hearing would determine if Rice and Poindexter were to stand trial for first-degree murder. Quickly, almost imperceptibly, recalled Poindexter, the boy winked at him and Rice, then took the stand to give his testimony. This time, he denied that he, Rice, or Poindexter were involved in the bombing. The state took a two-hour recess.

By the time Duane returned to the stand around 1:30 in the afternoon, his story had changed again. Wearing dark glasses, he spoke softly and was asked repeatedly to scoot closer to the microphone. Duane’s jittery, often convoluted testimony now supported the prosecution’s premise that Rice and Poindexter were the brains behind the bomb plot. At the end of questioning, Rice’s defense attorney, David Herzog, asked Duane to remove his sunglasses. An audible gasp rippled through the courtroom. The boy’s eyes were red and swollen from crying. Herzog excused him and Duane stepped down from the stand shortly after. Despite Duane’s changing testimony, Rice and Poindexter would stand trial for first-degree murder.

The Rice/Poindexter trial kicked off on April 1, 1971. Judge Donald J. Hamilton, a native Omahan and former Navy service member, presided over the two-week trial. Former Nebraska Gov. Frank Morrison joined the defense. At 65, Morrison was stout and distinguished, an anti–Vietnam War Democrat who’d defied the odds by being elected governor three times in predominantly Republican 1960s Nebraska.

In a memoir penned three years before his death in 2004, Morrison described the four years he spent as the Douglas County public defender as the most frustrating of his career. Racial tensions in Omaha were high, and Morrison wondered if Rice and Poindexter could have received a fair trial in such a charged atmosphere. Eleven of the 12 jurors selected for the Rice/Poindexter trial were white. “They had been very critical of one thing called police persecution of people of African descent,” he recalled. “I’m convinced they just set out to get some evidence on Rice and Poindexter ’cause they didn’t like the way they talked.” His clients stood a chance, Morrison knew, of being convicted based on rhetoric alone.

Quoting extensively from Panther papers, O’Leary indeed cast Poindexter and Rice as purveyors of hate. Rice’s poems and artwork, as well as his writing in the pages of the NCCF newspaper, stoked ire against “fascist pigs.” In O’Leary’s characterization, Poindexter, meanwhile, was the main architect of the crime who in the days before Minard’s murder boasted to Duane of his “beautiful plan to blow up a pig.” They were both brainy villains and the basest of bullies, men who had no qualms about sending a 15-year-old boy to do their dirty work.

Now 16, Duane Peak was the state’s star witness. In contrast to Duane’s cousins Frank and Will Peak, who denied that Poindexter met Duane at Frank’s house on August 10 or at the American Legion club on the 14th, Duane’s immediate family mostly corroborated his story. Duane’s sister Delia admitted to dropping Duane off on 28th between Ohio and Lake on the night of August 16. The last she saw of him, he was walking toward a nearby alleyway, suitcase in hand. Donald Peak described how Duane came to him the next day, crying, saying he’d killed a policeman. In a deposition taken in August, another sister, Theresa, claimed Duane admitted to killing Minard on his own, “because [he] wanted to.” On the witness stand, however, Theresa waffled. She couldn’t remember if Duane admitted to acting alone. Morrison read her previous statement back to her. “Did you make that answer at that time?” he pressed. “Yes,” she finally replied. “Similar to that.”

Duane himself was subdued but calm. His story was a variation on the previous one, with several notable differences. The bomb, he said, had been armed when he put it in the trunk of both his sisters’ cars and armed when he dropped it off at 2867 Ohio. In his latest retelling, Duane placed the case on its side in the doorway—rather than in the middle of the living room— the blue wire sticking straight up, where it would have been visible to officers entering the house. His intent, he said, was to scare police into treating “black people better.” He assumed the officers would notice the wire and disarm the bomb. “I didn’t want anyone to die,” he testified. The change in detail eliminated the need for Poindexter or Rice — whose alibis for the night of August 16 were both verified — to have gone to the house that evening to move the case closer to the doorway.

Duane described the basics of the bomb’s mechanics. The triggering device was a clothespin held apart by a wooden wedge and attached to six inches of blue insulated wire protruding from a nickel-sized hole in the side of the case. Neither of his sisters, their boyfriends, or children — who were in the car with Duane — noticed the hole or wire. Only Donald testified to seeing the wire, a detail missing from his original deposition.

Scraps of the suitcase that had survived the blast were presented as evidence by the prosecution. The suitcase was covered with nitroglycerin — residue that would have been consistent with an ammonium nitrate–based bomb such as the one used to kill Minard, according to the testimony of an agent from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF). Although dynamite residue had been recovered from Rice’s pants and Poindexter’s shirt pockets, neither man’s hands had tested positive for dynamite.

By the end of the 14-day trial, Morrison felt hopeful. The prosecution’s physical evidence, he felt, was inconclusive. The case came down, ultimately, to the credibility of Duane’s testimony. In his closing statement, Morrison depicted Duane as an unreliable, dishonest delinquent. “For the first time in my life,” he remarked, “I have seen the state try to convict basically on the testimony of one witness and that witness is an admitted perjurer.”

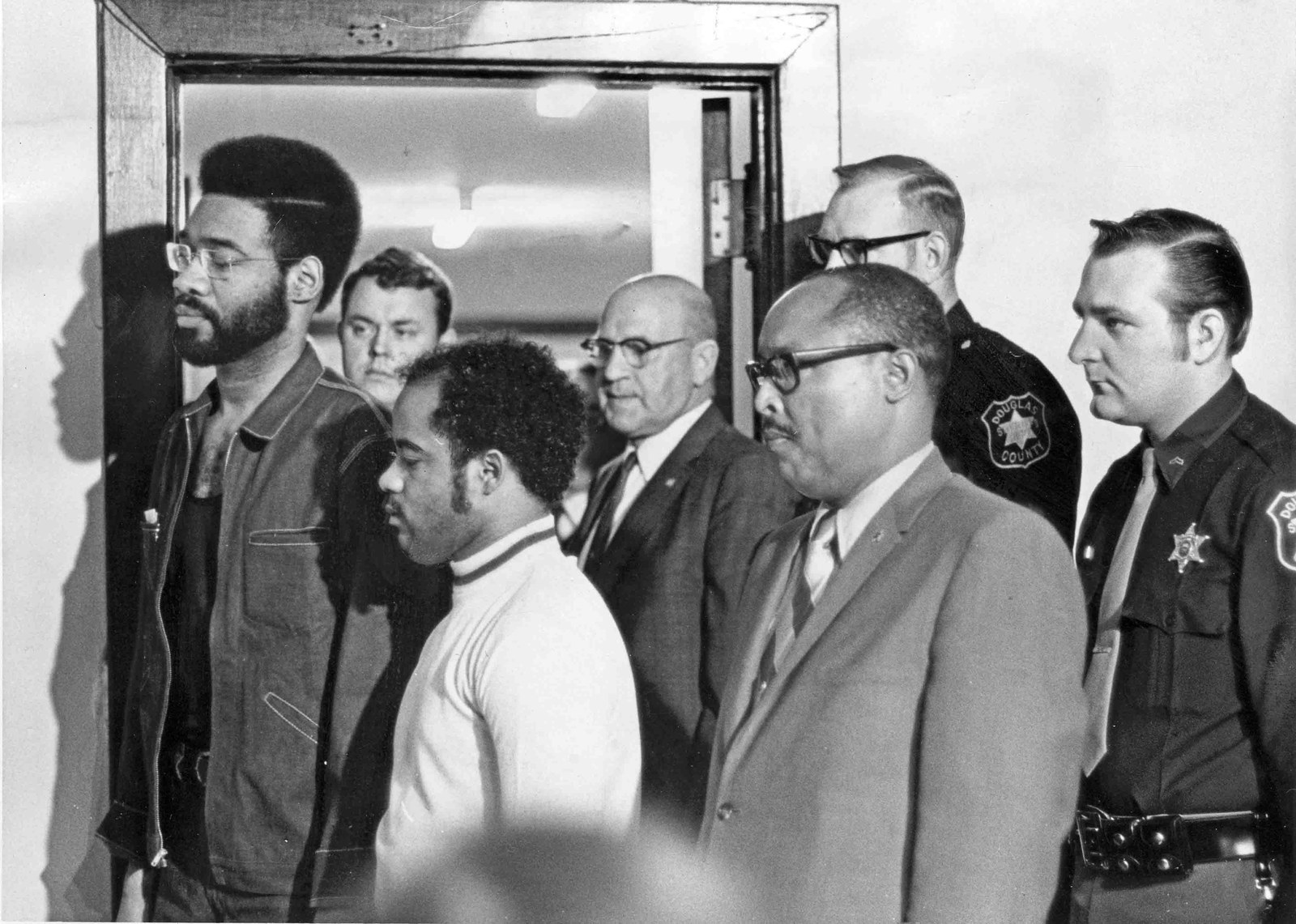

On April 17, after nearly four days and 25 hours of deliberation, the jury found Ed Poindexter and David Rice guilty of first-degree murder. They were sentenced to life in prison.

Within an hour of the jury’s verdict, Rice and Poindexter were taken from the Douglas County jail and led to separate cars. As the cars prepared to head from the courthouse to the Nebraska State Penitentiary in Lincoln, Rice called out to Poindexter: “Hey, man, do you want to drag?”

I met David Rice, now known as Wopashitwe Mondo Eyen we Langa, on an August afternoon a week and a half after the 45th anniversary of Larry Minard’s death. (I first heard about we Langa and Poindexter’s case through my father, who lived in Omaha in the early ’70s and reported on the Rice/Poindexter trial for the Omaha Star.) Now 68 and suffering from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), we Langa wears a breathing mask and uses a wheelchair. He was so stooped, his chin fell almost to his belly button, his face bowed so that I had to rest my elbows on my knees and hunch forward to be at his eye level. We sat side by side while, across the visiting room, Poindexter nodded at me but we didn’t speak. (A visitor is allowed to talk to only one inmate. That afternoon I was on we Langa’s visiting list, not Poindexter’s. Poindexter happened to be receiving a visitor at the same time.)

We Langa changed his name in the early ’80s as an attempt to reclaim his African identity. Wopashitwe Mondo Eyen we Langa means “wild man-child of the sun” and is an amalgam of African dialects (we Langa doesn’t know specifically where in Africa his ancestors are from). During our conversation, he referred me to his book, The Black Panther Is an African Cat, a collection of poems touching on the Omaha people and streets he knew and loved. His poetry is a revolt against disappearance: an evocation of a time and place often misunderstood. It’s also motivated by a desire to write black experiences back into history, an impulse made explicit in we Langa’s 2006 poem “From the Ancestors’ House”:

who were we but brothers and sisters

in search of brother-and-sisterhood

in a maze of europeanisms

that led us away from ourselves

and each other

Pausing between stories to catch his breath and take puffs from his portable nebulizer, we Langa stuck out a leg, and on a kneecap the size of a girl’s fist traced the outline of the interior of the white frame house he once loved. During the ’71 trial, the most damning evidence against we Langa had been the dynamite found in his house. He denies ever having dynamite and believes to this day that the dynamite was planted. Shaking his head, he described how one sergeant testified to finding dynamite stashed in a coal bin in his basement, but other officers' accounts differed on the exact location where the dynamite was found. His house burned down in May 1971, shortly after the trial. “It was a real cool house,” we Langa said sadly. He still misses dancing in the “Room of Darkness.”

We Langa’s best chance for a new trial came in 1974, when he filed an appeal in federal district court, arguing that the dynamite and blasting caps recovered from his home during a police search for Duane Peak should never have been received in evidence. The search of his home, we Langa argued, was illegal because the officers who entered had no probable cause that Duane was there.

During evidentiary hearings in December and March of 1974, U.S. District Judge Warren K. Urbom presided as Omaha Lt. James Perry testified that he was the one who put we Langa’s (then going by Rice) house on a list of places to look for Duane. He did so because Delia Peak told him that Rice, Poindexter, and Duane were “constant companions” — an assertion that, to borrow from Urbom, was in “no way corroborated” by the record. A police report of Delia’s interview on August 22 revealed nothing about Duane being a companion of either Rice or Poindexter, and the rights advisory form she signed indicated that only two officers — neither of them Perry — were present for her interview. Furthermore, noted Urbom in his decision, questioning of Delia Peak did not even begin until the very hour police first approached we Langa’s home, meaning that the interview was not completed until after the decision had been made to enter. Urbom ordered a new trial for we Langa without the dynamite and other items seized from his home, a decision affirmed by the 8th Circuit Court of Appeals.

Urbom’s ruling was invalidated in 1976 after the Supreme Court ruled on the landmark case Stone v. Powell, a ruling that limited prisoners’ rights to petition federal courts for a writ of habeas corpus. After Stone v. Powell, federal courts were no longer obligated to consider claims of illegal search and seizure if such claims had already been considered in state court. The ruling applied retroactively to we Langa’s case. He tried to appeal the search under the new rules, but his case was ruled out of time to file. According to Urbom in his 2012 memoir, the Supreme Court “did not find that the dynamite and accoutrements were legally found or that the Nebraska state courts had been right in allowing the use of that evidence at the trial. It found only that the federal court should not have taken the case.” Urbom’s decision on the illegal search of we Langa’s home has technically never been challenged. According to David Herzog, we Langa’s former attorney, he has been held in prison in violation of the Constitution since 1971.

If Poindexter and we Langa were granted a new trial today, their legal team would still have to contend with circumstantial evidence derived from ATF analysis of tools found in we Langa’s kitchen and dynamite residue recovered from we Langa’s pants and Poindexter’s shirt pockets. But poking holes in the physical evidence linking we Langa and Poindexter to the crime might not be such a difficult task. The science behind the forensics that helped convict we Langa and Poindexter, according to FBI whistleblower and former forensic scientist Fred Whitehurst, has serious flaws. In December 1999, we Langa's and Poindexter's defense teams brought Whitehurst to Omaha to review the evidence against the two men, as part of their investigative efforts to find alternate suspects in Minard's murder.

“Something doesn’t add up here, unless that evidence was salted.”

In a detailed nine-page report prepared for the defense committee, Whitehurst broke down several inconsistencies in the ATF lab work that linked we Langa and Poindexter to the crime. Most high explosives leave little to no residue, even when undergoing a high-level detonation. Finding dynamite particles in the debris of 2867 Ohio, according to Whitehurst, would have been almost impossible. Yet the suitcase scraps recovered from the scene of the crime were covered with nitroglycerin. “I find it hard to believe that anyone could find that much nitroglycerine in residue on that suitcase,” Whitehurst noted.

The process of building a suitcase bomb of the type that killed Minard also does not require that an individual’s hands make contact with the explosive. “One pokes a hole into the dynamite and inserts the blasting cap,” Whitehurst explained. The dynamite wrapper does not need to be opened to insert the cap. In other words: “There is no reason for dynamite particles to come out of that hole.” How, then, Whitehurst wondered, could dynamite particles have made it into Rice and Poindexter’s pockets? “Something doesn’t add up here,” he wrote in his report, “unless that evidence was salted.”

The voice on the tape — obviously male — is low and uninflected, the pace of delivery lumbering and not quite casual. He could be anywhere from 20 to 60, or even, conceivably, a preternaturally deep-voiced teen. “I’m here on 20, 20, 28th and Ohio, man,” he tells the operator. “The address is 28...2866 or 2867; it’s an old, vacant house. And, and this dude has drug this woman off. She’s screaming and shit and I don’t know what’s going on.”

When you listen to Duane Peak — at 51— speak these words, as Poindexter’s current attorney, Robert Bartle, and voice expert Tom Owen did back in February 2006, you might be struck by Peak’s crisply aspirated T’s in “20, 20, 28th and Ohio” or his clipped and quick delivery, so unlike the unenunciated utterances on the original recording. But likely, you’d first note the obvious: that Peak, full grown, cannot, could not, match the vocal depth of the unidentified caller, whose voice, he said, was his at 15.

Poindexter counts watching Owen play side-by-side recordings of Peak’s voice and the 911 tape during his 2009 post-conviction hearing as among his happiest moments. It was a moment he and we Langa had been waiting for since 1980 — when a copy of the 911 tape was made available to the defense for the first time, nine years after the trial. During Poindexter’s 2007 post-conviction hearing, defense attorney Herzog testified that while he had knowledge of a “voicegram” — a punch card that records the date, time, and instructions from a 911 call center — he was unaware of the existence of a tape recording of the actual 911 call at the time of the trial.

We Langa found out about the tape’s existence in the late 1970s after FOIA requests yielded an October 1970 memo from the Omaha FBI field office to J. Edgar Hoover. The memo stated that Omaha Assistant Chief of Police Glenn Gates did not want further analysis of the tape — which was being conducted at FBI headquarters in Washington — because use of the tape during the trial could be “prejudicial to the police murder trial against two accomplices of Peak.” The tape was never played in court. Lt. Perry (the same man who ordered the search of we Langa’s house) had ordered the destruction of the original recording in 1978, when we Langa and Poindexter were in the process of appealing their convictions. He told we Langa’s attorney in a 1980 deposition that the trial was “over as far as I was concerned.”

In October 1980, a copy of the recording was found in the belongings of a deceased 911 operator and turned over to we Langa’s then-lawyer. However, Peak’s location was not known to we Langa's or Poindexter’s defense teams until 1991, when Channel 4 filmmakers working on a documentary about BPP leader Geronimo Pratt and the Rice/Poindexter case tracked Peak down in another state.

Filmmaker George Case asked two of we Langa and Poindexter’s supporters — Nebraska State Sen. Ernie Chambers and reporter Ben Gray (now an Omaha City councilman) — to visit Peak. They showed up at Peak’s home unannounced. At the time of the interview, Peak was 36 and living alone, a father to two boys. His voice subdued and difficult to discern over the squawks of a pet bird, Peak described the stress and pain of testifying against we Langa and Poindexter. The consequences of not testifying, he told Chambers and Gray, were high. He entire family had been charged as accessories. “If you could have felt the inside of my heart, it was just like someone took a big brass drum and took it inside me and just started beating. I didn’t want to see my family suffer for anything they had nothing to do with,” he says, addressing Chambers 15 minutes into the interview.

Throughout the almost-hourlong taped conversation, Peak mostly stuck to his story — with two notable changes. At the end of the recording, Peak tells Chambers and Gray that he believes we Langa and Poindexter made the bomb in we Langa’s basement (during the trial he testified to watching Poindexter make the bomb in we Langa’s kitchen). Asked if he watched we Langa and Poindexter make the bomb, Peak’s reply is immediate: “No, I didn’t.”

Sixteen years later, in the 2006 voice analysis, Peak, who now lives under a different name, read from the transcript of the 911 call and was asked repeatedly to speak up. “It’s not the same person,” Owen, who recorded Peak over the phone from his office in New Jersey, testified during a 2007 hearing to determine if Poindexter would get a new trial.

Though the Nebraska Supreme Court offered no objections to Owen’s credentials, Owen’s analysis did not, they concluded, merit a new trial for Poindexter. In 2014, we Langa filed an appeal with the Nebraska Appellate Court, arguing that the FBI crime laboratory report on the identity of the 911 callers — the analysis that Gates did not want Poindexter's and we Langa’s attorneys to see — should not have been withheld from the defense. His petition was dismissed without opinion.

“Voice analysis isn’t as conclusive as DNA analysis,” said Poindexter’s attorney Robert Bartle, when I met him in his office in Lincoln last year, “because even if you assume it wasn’t Peak who made the 911 call, that doesn’t necessarily mean that Ed Poindexter is innocent. There’s no DNA test for perjury. Even if the voice analysis is believed, we can’t prove conclusively that Ed or Mondo [we Langa] couldn’t possibly have committed the crime or conversely clearly illustrate who did.”

In other words, that Peak may have committed perjury, the state argued in denying Poindexter’s 2009 motion for post-conviction relief, had little bearing on the outcome of the case — a claim that seems at odds with Gates’ concern over the tape’s release.

Poindexter and we Langa’s supporters — and a handful, even, of their detractors — aren’t so sure. In a 1978 Washington Post article, Douglas County Prosecutor Art O’Leary observed that the prosecution’s case hinged on Peak’s testimony, and acknowledged the possibility of a setup, telling the Post it was “a hard question” at the very least. The Post noted that O’Leary made a deal with Peak “to the extent that Peak would be tried as a juvenile in return for his testimony.” O’Leary later denied that he made a deal, claiming he was misquoted in the article. What’s clear is that Peak has spent most years since living under a changed name, several states and more than a thousand miles away.

The Post article was written in response to a list released by Amnesty International in 1978 of 21 prisoners in American jails whose incarceration was either likely or possibly tied to their political beliefs. Of those prisoners, two were white, two were Native American, and the rest were black. As of this year, each of the prisoners profiled in the Post, with the exception of we Langa, Poindexter, and Gary Tyler — who was a high school sophomore when he was convicted of killing a white boy during a racial disturbance over school desegregation in 1974 — are free.

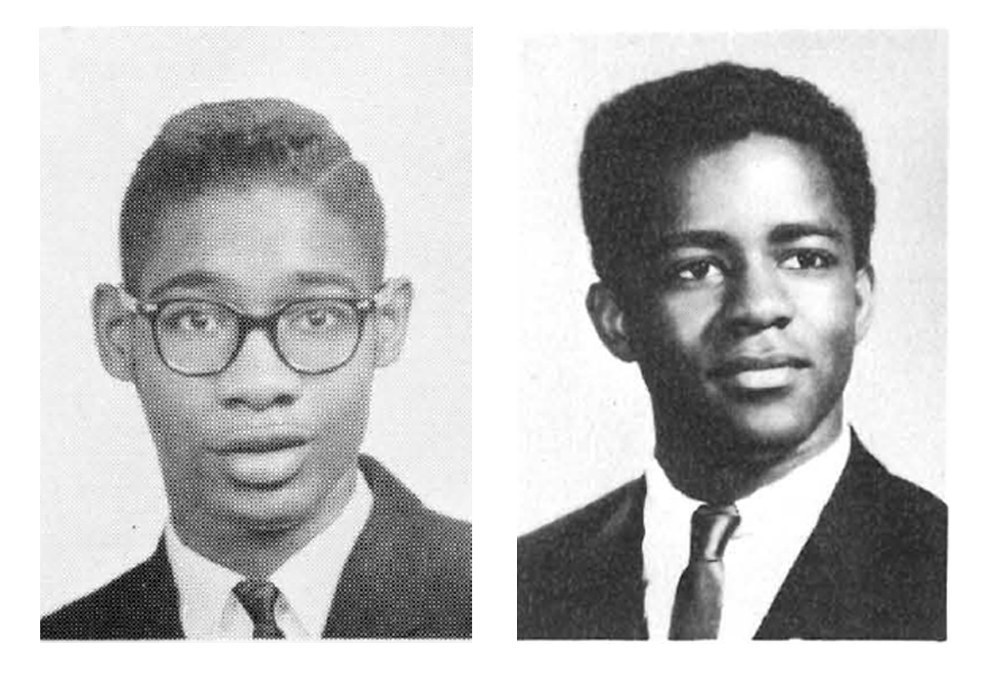

Edward Poindexter’s senior photo reveals a goofy-looking kid wearing oversize glasses and a dazed expression. His face has yet to fill out. In another yearbook photo, Poindexter, a track standout, stands proudly among other letter winners, his posture ramrod straight. He is the tallest of the bunch and one of just six black student-athletes. Unlike many of his stone-faced peers, he isn’t caught up in macho posturing and smiles broadly at the camera. It’s impossible to tell if his smile suggests earnestness or silliness, the face of a kid who takes himself too seriously or not at all.

His high school friends, including Frank Peak, who died in October, described Poindexter as a quiet and easygoing kid who played music and loved doing the pony during recess. Almost everyone I talked to who knew or knows Poindexter described him as shy and introspective. Of we Langa and Poindexter’s differences in personality and stature, Bartle reflected: “They really are Mutt and Jeff when you see some of their old file photos. Mondo, even when he was healthy and young, he’s a little guy. Ed stands about 6'5" and has a frame more substantial than mine. Mondo’s a lot more gregarious, a poet and freelance writer, and people complain that Ed many times really doesn't want a visit at all.”

His shyness, Poindexter speculates, stems partially from a childhood trauma. One afternoon, Poindexter’s father, a Pullman porter, came home tired from work. Poindexter, 8 years old, miscalculated his father’s mood and sat down on the carpet between his father’s legs to read the paper with him. His father snapped at him and slapped him across the side of his head. Poindexter ran upstairs to his bedroom, crying, “I hate you. I wish you were dead!” The following evening his father drowned in a nearby lake after a late night partying with his friends.

Already a private child, Poindexter could not bring himself to tell anyone what he muttered into his pillow the night before his father died. Afraid of his own words, he stopped talking for two years — from ages 8 to 10. “I was an introvert from then on,” he said, then added, “but an extrovert when I needed to be.” Over the near half-century he’s spent in jail, Poindexter has kept himself busy teaching computer and self-esteem classes. He’s at work on a memoir.

When I asked Poindexter what he would do if he got out, he laughed: “The first thing I would do is go clubbing.” He shimmied a little in his chair to an imagined beat, then paused, considering. “Actually, I probably wouldn’t want to go out. I’m a homebody. My ideal day, I would stay in, be at my desktop station with my typewriter and write all day. I guess that wouldn’t be too different from how my days are now.” If he gets out, he told me, he wants to go on a lecture circuit and get his self-esteem literature out in the world.

We Langa, meanwhile, publishes poetry and writes for the Omaha Star, the city’s black weekly newspaper, when his health allows. Unlike Poindexter, he has no desire to return to Omaha. If he gets out he wants to spend time in West Africa, particularly in Mali. “Mondo and I love each other, we’d die for each other, but we’re different. We clash all the time,” Poindexter said. “Mondo’s an idealist. He’s very stubborn. The other day we got into an argument about who the actress was in An Officer and a Gentleman. He thought it was Jessica Biel! I told him it was Debra Winger.” Poindexter laughed: “When I proved him wrong, he just got kind of quiet and said, ‘I got you, man.’”

"These weren’t the Panthers from Cleveland or the Panthers from California, but the police were deathly afraid of them."

We Langa’s stubbornness, according to his supporters, is simultaneously his most frustrating and most admirable quality. Gray worked as an advocacy journalist and hosted the public affairs television show Kaleidoscope for 30 years. Many of his episodes focused on the Rice/Poindexter case. In 1990, Gray and former Omaha NAACP president Buddy Hogan approached then-Nebraska Gov. Bob Kerrey, asking him to consider granting we Langa and Poindexter a pardon.

Kerrey was a liberal Democrat and, according to Hogan, seemed to care about Omaha's black community more than past governors. He would come often to North Omaha to eat. "It was the first time we ever saw a governor in the ghetto," Hogan recalled. He hoped that Kerrey would be willing to at least take a look at Poindexter and we Langa's case. To Hogan and Gray's surprise, Kerrey told them he would consider a pardon.

Elated, Gray and Hogan rushed to the penitentiary to tell we Langa the news (Poindexter was incarcerated in Minnesota at the time). We Langa, however, didn’t share their excitement. Accepting a pardon would imply guilt. “We’ve approached Mondo on several occasions, but his answer is always no. He’s not going to admit to something he didn’t do,” Gray told me. “I don’t disagree with it.” Neither Gray nor Hogan heard back from Kerrey.

“I just find it laughable what they did,” said Gray, who was in the military when he moved to Nebraska. “When I first came to Omaha I would see these guys carrying around guns and wearing black berets. It was clear to me they didn’t know how to handle the weapons they had. These weren’t the Panthers from Cleveland or the Panthers from California, but the police were deathly afraid of them. I was just worried they were going to accidentally shoot themselves.”

I showed up at Nebraska state Sen. Ernie Chambers’ office unannounced, the morning after I visited Poindexter. I had spoken with Chambers, a former mentor of we Langa's and Poindexter’s, previously; halfway through a brief phone conversation early last year, he politely turned down my interview request. He was tired, he said, of talking about Mondo and Ed. The stories never led anywhere and the subject was too sad. He was busy besides: in the midst of drafting a bill to abolish the death penalty in Nebraska — a bill he’s pushed in every legislative session in which he’s served since 1976. The bill passed last May. I hoped that now he would have time to see me, and I was nervous that he wouldn’t want to. It turns out, I shouldn’t have been.

Chambers, 78, was immediately warm. Despite launching into a running commentary on the uselessness of delving into the past, he eventually opened up to me about Poindexter and we Langa’s case. To this day, he believes they were framed. “There was so much about that case that didn’t make sense,” he told me bitterly. “The voice on that tape was like James Earl Jones, and Duane Peak’s was like Pee-wee Herman’s. There’s no way Pee-wee Herman can be James Earl Jones.”

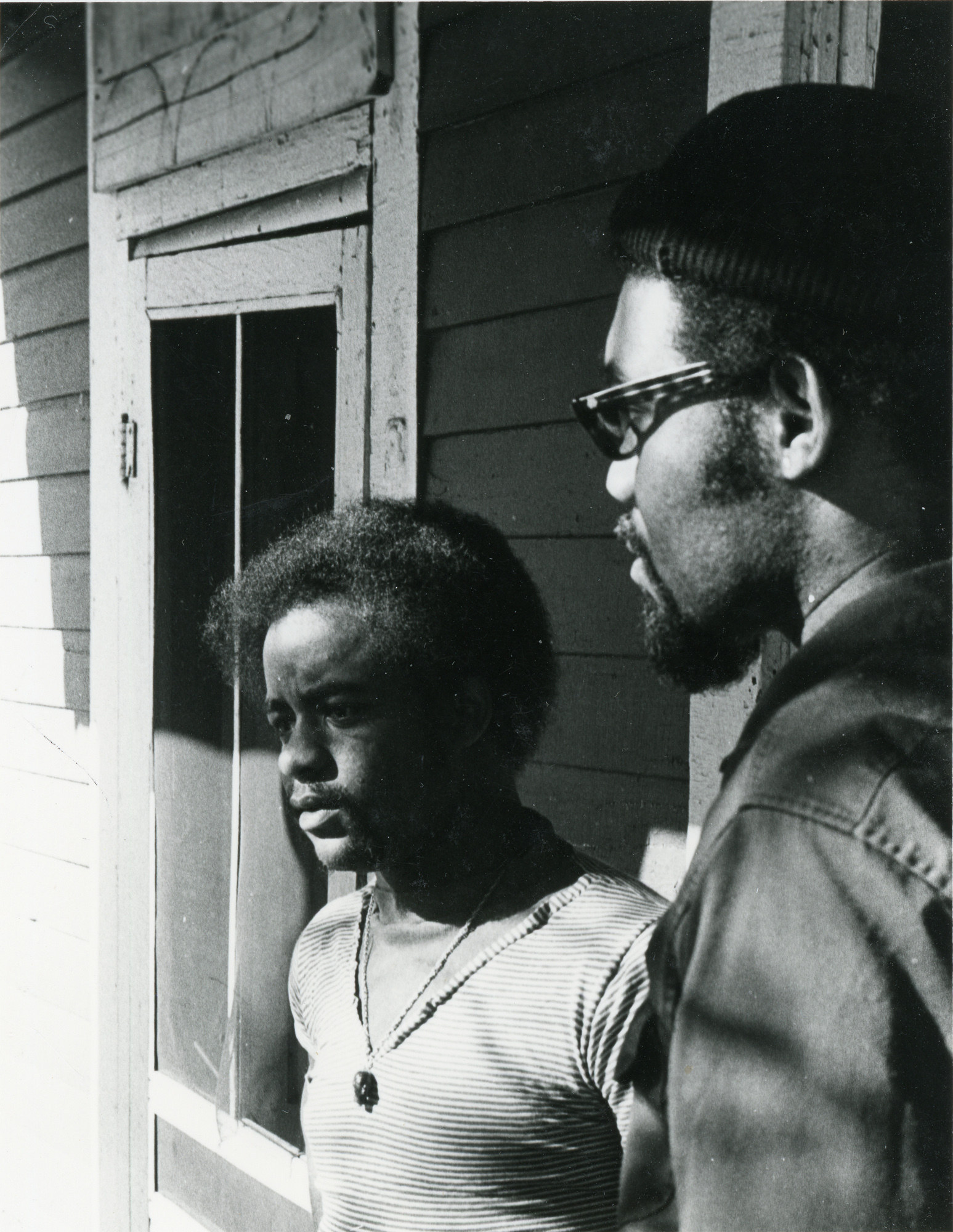

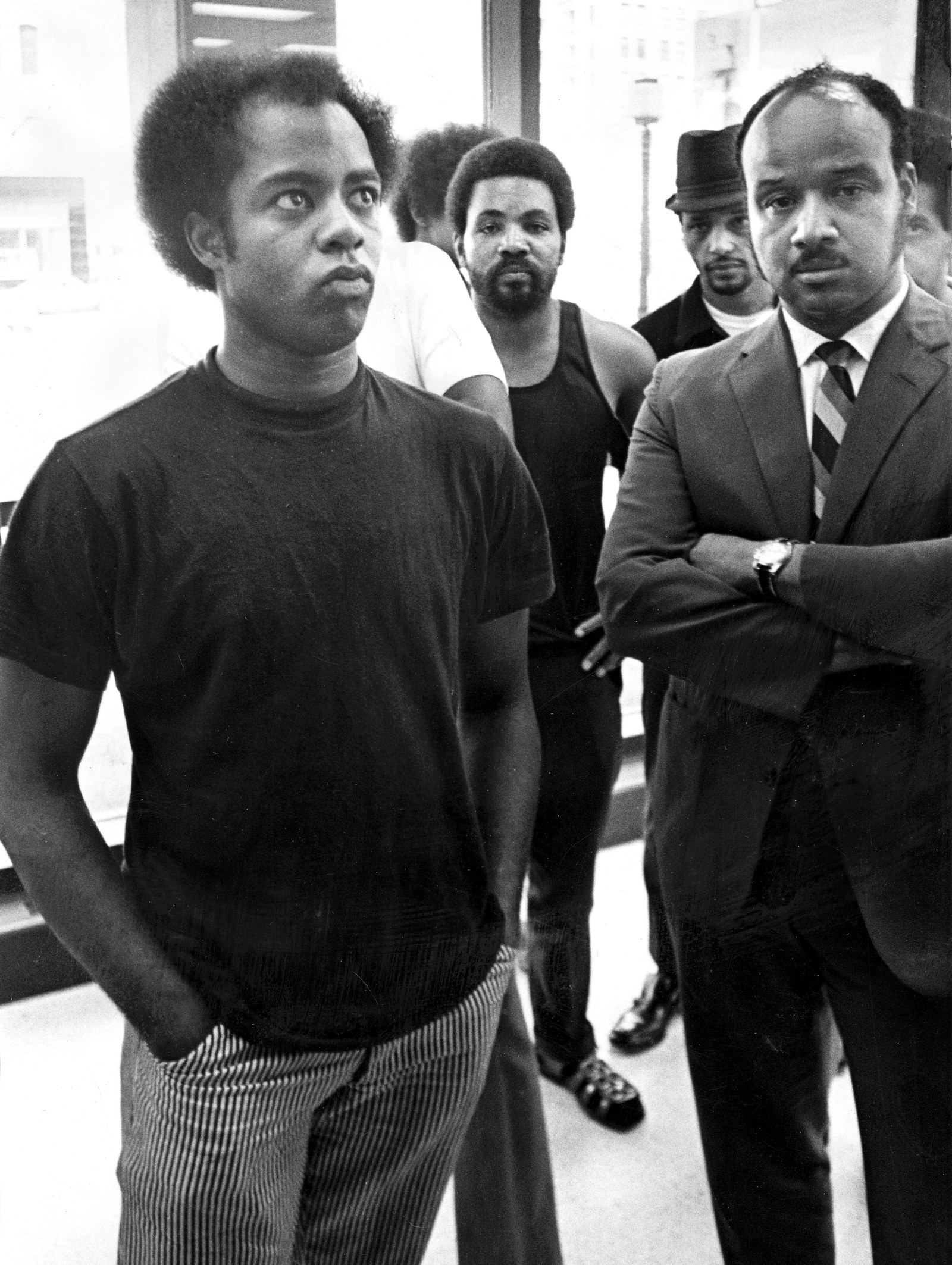

Casual in jeans and a T-shirt, Chambers didn’t look so different from his younger self, from the compact, muscular 33-year-old I’d seen in the background of an old photo from the World Herald. In the photo he’s standing behind Mondo we Langa, moments after we Langa turned himself in. They are waiting for an elevator in the police station lobby. Chambers is wearing a black tank top, his hands on his hips, staring straight into the camera. We Langa’s hands are deep in his pockets. The photo, Chambers told me, makes a strong case for we Langa’s innocence. It was taken immediately before we Langa turned his clothes over to police and had his hands and fingernails swabbed for dynamite. Dynamite particles were found in we Langa’s pants pockets. His hands and nails, however, tested negative.

Another aspect of the case that frustrates Chambers is that anybody would believe a 15-year-old kid could carry an allegedly armed suitcase bomb with a clothespin triggering device all over North Omaha for six hours. In 2014, freelance journalist Kietryn Zychal and Omaha activist Scott Blake made a three-minute trailer for an as yet unproduced documentary on the case. The clip retraces the steps Duane is supposed to have taken with the bomb in the hours before Minard’s death. During the trial an ATF agent testified that it would have been possible for a device of this type to explode accidentally if a person is carrying it around from house to house. “Any jar,” according to the agent, could have caused the little chip of wood holding the clothespin apart to fall out, triggering an explosion. Given the agent’s testimony, it is difficult to believe that the bomb would not have exploded while resting unstably in the trunk of Delia Peak’s car.

The Omaha National Committee to Combat Fascism had its headquarters in a duplex house near Goodwin's Spencer Street Barber Shop, where Chambers worked as a barber after graduating law school. He wasn’t old enough to be Poindexter's or we Langa’s father, but he was a mentor to them and many other young activists in the community. Mondo and Ed, Chambers explained, were like many other young black men in Omaha who “hadn’t found themselves yet” at the time. “Mondo was a tremendous optimist and idealist. As bad as things were in America, he didn’t think certain things would happen to him. Ed was more mature. He was not the one who would do a lot of the mouthing about. But when he talked, he would say the kind of things other members of the Panthers would say.”

“When it came to Mondo and Ed, they both had very good minds. But they said the standard things that Panthers said. They said, ‘Off the pig,’ ‘The power of the people is found in the gun,’" Chambers said. “The police didn’t know how much being said was bluster and how much might lead to something. I told them to use their intelligence, to express themselves without using words that will turn people off, but they didn’t listen.”

It wasn’t that Chambers didn’t share Poindexter's and we Langa’s anger. However, he knew that remaining even-keeled in the face of police harassment could be the difference between life or death, a life lived to its full potential or a life spent in jail: “A policeman would take a broken jaw if it would get me off the streets,” he said. Unlike we Langa and Poindexter, Chambers felt protected to some extent by his standing in the community. Still, through the Freedom of Information Act, Chambers eventually learned that the Omaha police had had him under surveillance. But they didn’t have anything on him. He was, in his own words, “clean as energy.”

“I was hoping after all these years Duane would come clean,” Chambers told me toward the end of our meeting last summer. “Most of those involved have died, but maybe Duane still thinks someone out there might be able to put the grabs on him. There’s still so much fear.”

“The thought of Mondo and Ed dying in prison is just not a thought I want to have,” said Ben Gray, voicing a sentiment shared by we Langa and Poindexter’s support team, chief among whom are retired Omaha cop Tariq Al-Amin and activists Mary Dickinson and Anne Else, a paralegal for human rights attorney Lennox Hinds, who has represented we Langa since 1991. Al-Amin, Dickinson, and Else are all leaders in Nebraskans for Justice, a committee formed to raise awareness of we Langa and Poindexter’s case. They also do legal work and fundraising. (Poindexter and we Langa’s attorneys work mostly pro bono.)

But the likelihood of we Langa and Poindexter dying in prison increases as each year passes. “The legal avenues are pretty much shut down,” Al-Amin said. There’s a slim chance the case could be reopened, if we Langa's and Poindexter’s defense teams could uncover new evidence. For instance, a key to unraveling the case could be a seemingly minor player, Marialice Clark, the younger sister of one of Poindexter’s girlfriends and a friend of Duane Peak’s. Clark disappeared in August 1972 when she was 14.

"The voice on that tape was like James Earl Jones, and Duane Peak’s was like Pee-wee Herman’s."

Marialice's name appears on an affidavit for a search warrant applied for by ATF agent Tom Sledge on July 20, 1970, when she was 12 years old. The affidavit refers to her as a “woman” and not as a minor. Sledge said Marialice was present when five NCCF members — but not we Langa or Poindexter — made a bomb out of dynamite at headquarters. The Department of Justice in Washington ordered the agent to return the warrant to the court unserved after an FBI informant inside the chapter said there were no machine guns or dynamite in NCCF headquarters. They didn’t want a repeat of the raid in Chicago that killed Panther leaders Fred Hampton and Mark Clark, shot to death in a late-night raid at Hampton’s West Side apartment. Two years later, Marialice disappeared.

Marialice’s family was never told about the ATF affidavit until 1995, when Zychal showed up at a school where Marialice’s sister Vicki was working. Marialice, her family maintains, never told her family and friends that she saw five men make a dynamite bomb, nor did she ever mention to them that she had been interviewed by an ATF agent.

In February, Marialice’s brother Ed Clark posted a petition on Change.org urging the Department of Justice to investigate how an ATF agent could put the name of a 12-year-old girl on an affidavit without informing her mother. If the agent lied on the affidavit for the search warrant, it could open an investigation into how he handled evidence in we Langa and Poindexter’s case, as well as a larger investigation into possible counterintelligence programs spearheaded by the ATF, similar to the FBI’s better-known Cointelpro. But even if new information about Marialice Clark’s disappearance surfaced, there would still be the challenge of finding another judge willing to consider new evidence.

Al-Amin and Else feel that we Langa and Poindexter’s best chance for release lies with the Nebraska Board of Pardons. In order to be eligible for parole, Poindexter and we Langa’s life sentences must be changed or commuted to a specific number of years. Beginning in 1993, the Nebraska Parole Board voted for six years to recommend we Langa and Poindexter for parole. The Pardons Board declined to commute their sentences. Nebraskans for Justice is asking citizens to write Gov. Pete Ricketts urging the Pardons Board to commute we Langa's and Poindexter’s sentences to time served in light of their deteriorating health. It’s a long shot. Ricketts is a Republican known for being tough on crime.

“When the victim is a policeman, every time there’s an appeal the courts kowtow to them,” Else said. “So that’s a whole other issue that’s at play when the decisions come down.”

“You hope that political winds change, but I doubt it,” Al-Amin said.

Meanwhile, Poindexter and we Langa struggle with new and ongoing health issues. We Langa’s condition is particularly grave. He’s been in and out of the prison infirmary and a Lincoln hospital since the fall. As COPD worsens, a patient’s lungs deteriorate, putting pressure on the abdominal area. At 105 pounds as of February 7, we Langa is having trouble eating and gaining weight.

Despite the grim prognosis, we Langa is determined, he said, to live to see his freedom. What haunts him most about the case is the idea that people would believe him capable of putting a 15-year-old in harm’s way. “If you have some kind of commitment that you need to carry through, you don’t put the lives of children in jeopardy.” He feels no anger toward Duane Peak.

Though we Langa has long maintained he would not consider compassionate release and wants to be freed solely on the basis of his innocence, he recently agreed to allow his defense team to file a petition to the Nebraska Board of Pardons, as long as a second petition for wrongful imprisonment is also filed. We Langa’s 10-year parole hearing will occur in December 2016. Nebraskans for Justice recently secured a new lead attorney who will work with Hinds as they prepare to file the petition and for the eventual parole hearing, granted we Langa is able to hang on for another year.

In December, Poindexter wrote to Duane Peak to inform him of we Langa’s deteriorating condition and to urge him to come forward, but Peak returned the letter unopened. I called Peak back in November. When I mentioned the Rice/Poindexter case he told me he didn’t know what I was talking about and hung up. The phone call lasted under a minute. Weeks later he returned a letter I sent him, unopened.

I visited we Langa in the penitentiary infirmary on Super Bowl Sunday. “I’m rooting for the Carolina Panthers,” he joked, a few hours before kickoff. “I bet you can guess why.” Though he was tired from waking up breathless at 5 a.m. — he spent much of that morning undergoing breathing treatments — he was in good spirits. At one point, he began to sing a version of “My Favorite Things” with the lyrics adapted to fit his interests. He used to perform the song in clubs around Omaha in the late ’60s and he continues to update it. “Johnny Coltrane, sex, and Dizzie Gillespie,” he sang, then louder, “Matchbooks and drums and India Arie. These are a few of my favorite people and things.”

After we Langa finished, I repeated a question I had asked Poindexter months earlier: “What would you do to celebrate in Omaha if you got out?”

He paused for a moment, then frowned. “If I got out, I would feel relief, but I wouldn’t celebrate. People say when they get someone out of prison after a wrongful conviction that it’s a cause for celebration, that it’s a sign that the system works. But the system failed me. The system failed Ed. Forty-five days would have been too long. Forty-five years? Well, that’s a travesty.” ●

The author would like to thank Kietryn Zychal and Scott Blake for their invaluable research assistance with this story.

Want to read more stories like this? Sign up for our Sunday features newsletter, and we'll send you a curated list of great things to read every week!

CORRECTION

Duane Peak changed his original story on August 31 and Lt. Perry told we Langa's attorney that the trial was "over as far as I was concerned" in a 1980 deposition. An earlier version of this story misstated the date and to whom Lt. Perry made that statement.