“It’s hard to get people to talk about the past in Cambodia,” says Charles Fox, “whether that’s due to emotion or fading memories.” The best way to retrieve stories about life before and after the Khmer Rouge regime, the British photographer found, was through photographs.

Fox created Found Cambodia, an ongoing digital archive that offers an alternative look at the country’s complex history, showing how a society has remade itself in the wake of genocide. The long-term project – 17 April marks the 40th anniversary of the fall of the Cambodian capital to Pol Pot’s regime – brings together citizen snapshots and studio portraits from before and after the Khmer Rouge.

Found Cambodia is an ever-growing account of family life supplied by locals who have entrusted Fox with their pasts. The results are striking, touching and sometimes amusing – but above all, they show how people can triumph over tyrants.

Fox is not interested in the usual pictures that get framed and hung on walls – photos of weddings, graduations, grandchildren – but the ones that are hidden, torn and scuffed and stuffed away. “Everything is kept in plastic bags or in the back of cupboards,” he says, “and a lot of them haven’t been cared for. But these memories must be preserved.”

He first travelled to Cambodia in 2006, where he lived in Phnom Penh and stayed on, freelancing for the Cambodia Daily newspaper. He returned to the UK in 2008, where he met a Khmer artist living in England. The man, Yanny, later shared his family photos – pictures his mother had managed to save and smuggle into the UK. Fox was fascinated, and thought there was a bigger story to tell. He started tweeting one of Yanny’s pictures every day.

Fox then moved back to Cambodia in 2012, where he has since sifted through thousands of images. “You have to have that obsessive streak,” he says. Though the memories are difficult to share, people have, more often than not, welcomed him into their homes; and once he explains his project, they start combing through their troves. Fox selects each shot “based on the strength of the image and the strength of the narrative”, and he only posts physical prints, because that lets him meet individuals and hear their stories. Each image includes a quote from its owner about the image.

But he never forces revelations. “This isn’t me chasing a story,” he says. “I don’t have to convince anyone; people have to be willing to share.” While the language barrier can cause problems – he’s assisted by a translator – there can still be a catharsis for the people he interviews. “After the Khmer Rouge, there’s a lot of joy,” he says. “But when you start talking about before, it’s a dark time. There is a lot of trauma embedded in these images. When they share their stories, it comes out.”

He recalls how one woman he met had created a family portrait with each member’s most recent passport photo. “It was so mixed up: someone who was young then is now older than [the person] in the photo who had died during the Khmer Rouge.”

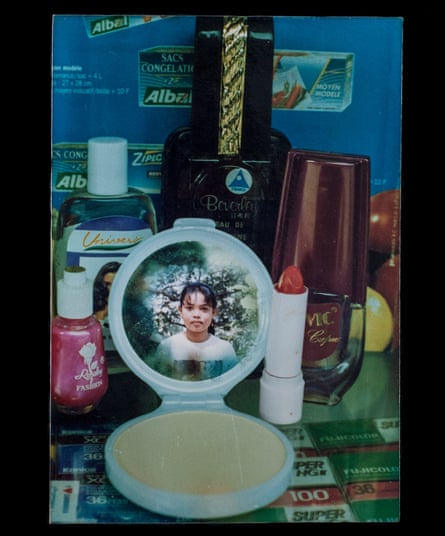

Fox’s investigation reveals not just a scarred country as it heals, but trends in photography. Cambodian photographers are fans of funny and improbable hybrid portraits, in which radically unrelated photos are spliced in the darkroom: a couple are superimposed so they’re standing on a tortoise’s back; a giant face floats above a field of flowers; a man wearing aviator glasses hovers beside Angkor Wat. There are heaps of fanciful studio portraits, and black-and-white images have been hand-painted, bringing lipstick and bouquets blooming to life.

People also made special records of their possessions. “There’s a double portrait where a husband and wife have both had their photo taken with a motorbike, in exactly the same spot,” says Fox. They have gone from having nothing, he explains, “to all of a sudden, having something – which becomes worth documenting.”

The site is arranged by date, but a lot of guesswork is involved in identifying the images. Most poignantly, the time prior to the Khmer Rouge’s reign is simply categorised as “before”.

“What’s been presented in the press and the history books doesn’t translate into the day-to-day lives of these people,” says Fox. It’s hard to grasp what people went through and witnessed during those years – forced evacuation, isolation, torture, starvation, exhaustion, execution – but witnessing the aftermath in pictures and stories is moving, even without grasping all the chilling details of the country’s history.

This archive deftly gives a personal face to the Cambodian genocide. The goal, says Fox, is to “give a gentle insight into people’s day-to-day, and how they’ve rebuilt themselves. I like that softer, more personal side. People make a country, people make a culture.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion