In every corner of Iran, one is reminded that artists were once the bloodline of towns and cities. This was a land where art permeated the everyday - in dishes, on walls, in the delicate Eslimi (Arabesque) carvings on copper bowls used to pour water over one’s head in a public bath.

What is left of it all today? True, Tehran remains a city where art thrives - in a tiny auditorium where tribal Arabs from Khuzestan have come to sing, in patterned displays of flowers beside highways, on stages where performers bring new stories to life.

In everyday objects however – dishes, shirts, shoes – such excellence has long been lost. The consumer economy is one in which the handmade demands high prices and is not thrown around in a public bath, which anyway is no longer there.

The bowls and textiles that once adorned the most humble homes, all bearing the mark of artists, are now museum pieces, replaced by cheap goods from China, India, Bangladesh. The pottery workshops of Meybod, Yazd province, once known as one of Iran’s primary pottery centres, are in a dire state. Cheap pots from Turkey have sent their business into sharp decline.

The fish, birds and faces drawn on pitchers or bowls are now sloppy and mediocre. “We have to keep costs low, so I’m not going to tell the younger apprentice to spend an hour painting one bowl,” one workshop owner told me.

In most cities, craftsmanship has died out. What survives - pottery, a few instances of embroidery and carpets - is what wealthy city-dwellers are willing to buy. But while Tehran’s Villa Street, once the capital’s centre of Iranian handicrafts, supplies more and more Chinese and Turkish goods, there is an artistic revival taking place.

Like handmade art in most urban settings, it belongs to the wealthy, but it is taking strong footholds, especially in Tehran. The first glimmers were seen more than a decade ago with the emergence of fashion designers working on women’s wear, but it has expanded further to include pottery, jewellery and other handicrafts.

This article includes content provided by Instagram. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. To view this content, click 'Allow and continue'.

Across northern Tehran, from Khaneyeh Javan in upper Shariati Street, to Art Gallery in Qolhak, to Manzeleh Parsi in Mirdamad, are shops specialising in Iranian handmade art and decor. Most have opened in the past three years.

The aim is a non-virtual Etsy store, a marketplace for handmade goods. “Business is thriving,” said one store owner in Eskan shopping centre, who specialises in pottery.

Artisans across Iran are in dire need of such outlets. “We need a permanent location to sell in Tehran,” one potter from Hamedan told me this summer at the annual handicrafts exhibition. “This exhibition does us a world of good but it is only for five days.”

The new northern Tehran stores do not, however, carry work by traditional artists from the provinces but of young, hip ones working in Tehran and major cities. The message is clear: for art to survive, trendy urbanites have to like it.

Traditional artists working in smaller towns have less access to high speed internet or online selling, and are less social media savvy to begin with. The pottery masters I met in Meybod do not even use the internet, whereas the younger generation featured in stores are doing well online through domestic sales.

This article includes content provided by Instagram. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. To view this content, click 'Allow and continue'.

While the re-emergence of local usable art is welcome, there is much copying. Cushions, scarves and pots all feature prints with no original artistic work.

A Safavid-era miniature on a scarf, a Qajar girl on earrings, a tile from Golestan Palace on cushions, pomegranates everywhere: placing traditional patterns on new objects has become highly popular. The vivid colours of the past add whimsy to any home or attire, but the merchandise itself is a consumer good.

To find authentic works of art, one has to look more thoroughly. The jewellery makers, Toktam & Bahram of Persian Garden, the pottery of Parisa Heydari, the intricate, graceful woodwork of Yasser Yami are all excellent examples.

This article includes content provided by Instagram. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. To view this content, click 'Allow and continue'.

These are young artists who make a living through their craft. Despite pricing wooden bowls from 300,000 to 800,000 tomans (£65/$100 to £175/$267), Yami sold his entire collection at the Tehran handicrafts exhibition in June.

Toktam & Bahram and Parisa Heydari are both husband and wife teams who expanded their business despite economic sanctions, which mean artists can sell to foreign markets only when they travel there.

Parisa Heydari and her husband Vahid Ansari work with a team of five artists in west Tehran. She is the name and creative director behind the brand, while he is the pottery artist and the business mind. Both originally from Tabriz, one of Iran’s pottery centres, they create serene ocean blue bowls, plates, vases and candle holders.

Parisa was a maths major, Vahid once an engineer. She is soft spoken and shy, he is enthusiastic and articulate. Unsettled with her work at university, she pursued pottery classes on the side.

They have showcased their work in Moscow, Milan and Algiers, but they began their work in the workshops of Tabriz, under such renowned artists as the late Qabchi brothers. Their workshop has received many prizes, including Tehran’s outstanding pottery award handed out by the Iranian Heritage Organisation.

Bahram Fazel of Persian Garden is a former communications engineer. Originally from Abadan, southern Iran, he came to Tehran during the Iran-Iraq war and in the antique shops of downtown Tehran he discovered master painting, including negargari (traditional Iranian painting) and calligraphy.

When he met Toktam Fazel, a jewellery maker, a collaboration (including marriage) was born. “It’s as if everything we do today was fated to be done,” he told me. “When I look back at all those smaller stories in life, they seem to bring me to this place.”

There is a wide range of designers offering jewellery in Tehran: Zargoon, Sara Kaidan, Ziv, Qeran are among them. Most use Qajar prints, or familiar silver patterns. Others, like Qeran, take inspiration from both prints and everyday objects.

This article includes content provided by Instagram. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. To view this content, click 'Allow and continue'.

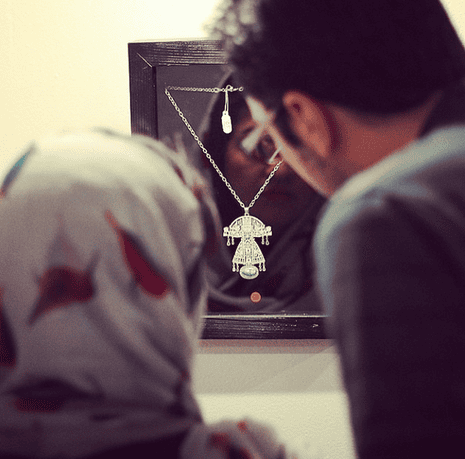

But in this new wave of jewellery makers, Toktam & Bahram are in a league of their own. For one thing, unlike all those other brands, they do not sell in any store. They have a showroom in northern Tehran, and also exhibit at the prestigious Golestan Gallery once a year. Speaking almost unison, they explain: “What we create is our child. You know how parents are always thinking of where to send their children to school? They are picky, they are worried - that’s how we are.”

This article includes content provided by Instagram. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. To view this content, click 'Allow and continue'.

Their work draws on poetry, architecture and traditional arts. They have an entire series that invokes the Persian garden - blue pools, fish, birds, and trees but set up in three dimensions to become jewellery, art and sculpture. They layer techniques to stunning effect, tireless and unique in a market where copying both the traditional and current arts seems the norm.

What is striking about both Persian Garden and Parisa Heydari is a familiarity and comfort with Iranian art, old and new, and ability to transform it into their desired forms. It is contrast with the many artists who lack sound knowledge of what has been done before, although they produce Qajar and pomegranate prints ad nauseam. When I ask a 27-year-old fashion designer about the miniature prints on her shirts and manteaus, she just replies: “I thought they were nice and colourful.”

Toktam and Bahram tell me that many of their pieces featuring birds were inspired by Attar’s Conference of the Birds, a Sufi tale of the quest for truth led by a hoopoe guiding a congregation of birds to the simorgh.

“There is a verse, ba tan nagooyam hich raz (‘secrets I will tell no one’), that was the inspiration for our Morgh-e Raz (Bird of Secrets) series,” says Bahram. “I began thinking of what the bird is, what the secret is, how it would appear, and then started sketching.”

Parisa Heydari, though working in a different medium, reiterates reverence for the artistic tradition. She primarily uses ocean blue glaze that echoes turquoise, the legendary stone mined for more than two millennia in Neyshabur, north-eastern Iran, and which has inspired poetry, architecture, and art throughout the ages.

This article includes content provided by Instagram. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. To view this content, click 'Allow and continue'.

Her pottery features delicate flowers, birds and more complex geometric patterns she says come to her through decades of looking at Iranian pottery. The clay comes from Zonuz, near Tabriz, long known for its “white earth” used in pottery and ceramics.

Why the re-emergence of handicrafts now? Heydari believes that in the past decade there has been more demand for Iranian art to adorn the home, whereas previously, people wanted foreign pieces: “Our pottery artists are gaining more academic training, learning new methods and ways, and with that comes ingenuity. People are looking at these works and thinking they might fit better in an Iranian home.”

This article includes content provided by Instagram. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. To view this content, click 'Allow and continue'.

Artists like Parisa Heydari have managed to capture the attention of people no longer interested in traditional arts. They do this by creating art with a modern twist that is authentically within the object - part of its “essence” as Attar says - and not just a print slapped on merchandise.

I remark to Toktam and Bahram that I work on tazhib (‘illuminated manuscript’) patterns and often wonder why more artists do not draw upon what already exists. They either copy an entire page, or ignore it.

“A twist of a flower petal, lanceolate leaf patterns, the movement of the Eslimi loops,” I suggest.

Bahram nods: “That’s precisely what we think. We wanted to take these fragments and build something entirely new that is also both familiar and novel, to remind people that these rich legacies live on.”

The Tehran Bureau is an independent media organisation, hosted by the Guardian. Contact us @tehranbureau

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion