Greater competition is crucial for creating better jobs, although there may be short term tradeoffs.

Job creation on a massive scale is crucial for sustainably ending extreme poverty and building shared prosperity in every economy. And robust and competitive markets are crucial for creating jobs. Yet the question of whether competition boosts or destroys jobs is one that policymakers often shy away from.

It was thus valuable to have that question as a central point of discussion for competition authorities and policymakers from almost 100 countries – from both developed and developing economies – who recently gathered in Paris for the 14th OECD Global Forum on Competition (GFC).

According to World Bank Group estimates the global economy must create 600 million new jobs by the year 2027 – with 90 percent of those jobs being created in the private sector – just to hold employment rates constant, given current demographic trends.

Yet the need goes further than simply the creation of jobs: to promote shared prosperity, one of the urgent priorities – for economies large and small – is the creation of better jobs. This is where competition policy can play a critical role.

Competition helps drive labor toward more productive employment: first, by improving firm-level productivity, and second, by driving the allocation of labor to more productive firms within an industry.

Moreover: Making markets more open to foreign competition drives labor to sectors with higher productivity – or, at least, with higher productivity growth. Making jobs more productive, in turn, generally increases the wages they command.

That’s in addition to cross-country evidence on the impact of competition policy on the growth of Total Factor Productivity and GDP, and the fact that growth tends not to occur without creating jobs. Thus there’s compelling evidence that – far from being a job killer, as skeptics might fear – competition (over the long term) has the potential to create both more jobs and better jobs.

The key question then becomes whether such long-term benefits must be achieved at the expense of short-term negative shocks to employment – especially in sectors of the economy that may experience sudden increases in the level of competition.

Progress toward better jobs is driven partly by the disappearance of low-productivity jobs, as well as the creation of more productive jobs in the short run. Competition encourages that dynamic through firm entry and exit, along with a reduction in “labor hoarding” in firms that have previously enjoyed strong market power.

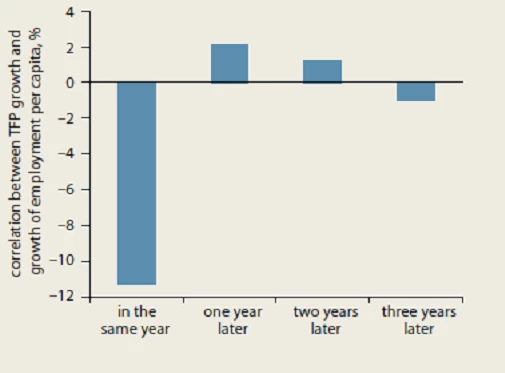

Two observations from Bank Group research add further perspective on the short-term impact. First: The short-term dynamics of the labor market are generally characterized by more jobs being created than destroyed every year. Second: The negative employment effect of a surge in Total Factor Productivity is usually reversed after a one year adjustment period.

We can think of this competition-driven process, then, as one of transformation – propelling workers from low-productivity, low-quality jobs to higher-productivity, higher–quality, higher-wage jobs. Of course, as with any economic transformation, the short-term impact involves some costs – to various degrees, depending on each industry’s context.

Thus, there can be no definitive answer to the question, “Does competition create or kill jobs” – The only answer to that question can be, “Which jobs? In which sectors? Over what time frame?”

The answer to these questions is likely to depend on the source of the increase in competition – that is, the type of reform driving the change.

Competition reforms: A strong link to jobs and scope to build evidence on impact.

At the Bank Group, we’ve worked with many partner countries to strengthen competition through various reforms. Many of those interventions provide mechanisms for the creation of more and better jobs.

In Rwanda, the Bank Group, in 2012, advised the government on the design of a competitive bidding process for green-leaf tea by two state-owned tea factories. Given that the tea sector is the third-largest employer in Rwanda, such reforms can be expected to have a strong impact on jobs. As a result of this initiative, the country’s 60,000 tea farmers saw their incomes increase by an average of 35 percent.

In Kenya, there were similar results in the tea sector in 2013 after the Competition Authority facilitated the licensing of a specialty tea factory whose entry had previously been blocked by incumbents. This entry allowed smallholder farmers (who the Bank Group considers as job-holders) who switched to the specialty tea to realize a 230 percent increase in the price paid per kilo for their product. This rise in the returns producers can achieve illustrates one aspect of what we mean by better jobs.

Such results prompt further questions that demand additional research: Do these income effects vary over time? Are there “spillover effects” on producer participation and incomes in other sectors? Does the threat of entry affect the type of supply contracts implemented in other sectors – for instance, contracts that might prevent farmers from switching? How do the effects vary across skill levels and income levels? (For example: Given that switching to a new crop is costly, and that cultivating a specialty tea requires certain additional skills, there may be distributional impacts.)

In the retail sector in Oaxaca, Mexico, a continuing Bank Group initiative to increase competition amongst retailers by easing restrictions on extended shop opening hours is expected to stimulate employment. Here one question would be whether total earnings differentials between genders might increase if women are more constrained by traditional household roles in the hours they work. On the other hand, greater competition could also lead to a narrowing of the gender earnings gap – as seen in various sectors in other economies.

The path to long-term gains from reducing barriers to trade and foreign investment is shaped by domestic competition and adjustment costs.

These previous examples have focused on domestic firms – but reducing barriers to trade and foreign investment can also affect the level of competition.

By integrating into global value chains, and by increasing exposure to foreign competition, economies can benefit from higher productivity and stronger growth in the long run. Granted however, these benefits involve some adjustment costs in the short term. This holds regardless of whether the impact is from foreign or domestic competition.

And those costs can be a very real concern, particularly for developing economies. World Bank research, in fact, finds that labor-mobility costs for developing-country workers are more than twice as high as for those in developed economies.

These concerns are influenced by many complex factors, including: labor-market regulations; sector characteristics; the degree to which the increase in competition triggers innovation or technological change; the skill level and educational attainment of the population; and any cost-mitigating policies, such as retraining programs or wage subsidies.

However, some evidence suggests that after an adjustment period, opening markets has a positive effect. As an example, a 2014 Bank Group simulation showed that liberalization of the food and beverage sectors in 47 countries would (in all but four countries) lead to higher real wages in that sector – and higher employment in other sectors – after an adjustment period, averaging around 5 years for developing countries.

One key factor affecting the benefits from opening economies to foreign competition is the level of domestic competition. Many studies show that domestic competition is vital for trade liberalization to have a positive distributional impact. That impact shows up in terms of the benefits being passed through down the value chain to developing-country producers, and in terms of bolstering the relative wages of less-skilled workers.

So, instead of hindering the transformation process, the primary role of competition policy authorities will be in driving that transformation. At the same time, other government agencies should be tasked with minimizing policy frictions that can make adjustment costs unnecessarily high.

Competition authorities can play a key role in building evidence to counter negative public perceptions.

The concerns discussed here underscore the important role that policymakers – like those assembled at the GFC – must play in ensuring that domestic competition is not undermined by anticompetitive barriers or behavior.

Indeed, during the GFC several competition authorities highlighted the importance of avoiding the trap of implementing government interventions which, although on the surface intended to protect employment, were more likely to harm competition and job creation in the long run.

Singapore cited its Jobs Credit Scheme – which was offered to all firms in a nondiscriminatory way during the global economic downturn – as an example of an intervention designed to avoid this trap. Morocco described how the privatization of its SOEs had been implemented without a strengthening of competition in privatized markets, meaning that the country had not fully benefited from the positive employment effects of firm entry and reallocation towards productive firms.

Political pressure associated with job losses was reported by several countries. A key point of discussion was the need for competition authorities to advocate for the long-term benefits of competition to counter special-interest groups and the (often very visible) negative impacts in the short term. As an example, Costa Rica’s telecommunications regulator (SUTEL) explained that releasing data about the past effects of telecom liberalization on employment has helped to allay concerns regarding future reforms.

Countering negative perceptions and political pressure will require strong evidence to capture the widespread and dispersed long-term job effects in a way that is meaningful to policymakers and the public. And as progress is made in terms of the data and methodologies available for this, competition authorities have an important role to play in documenting the benefits of competition enforcement and opening markets.

Join the Conversation