San Ramon is a forgettable commuter-belt city in northern California. There’s a Chipotle Mexican Grill, a handful of nail salons and the corporate offices of AT&T. But most notably, at least for me, it is the location of a large industrial freezer containing our four potential children.

Three years ago, my husband and I went through three rounds of in vitro fertilisation (IVF) to conceive our second son, Zeph. We already had one boy, Solly, made easily the old-fashioned way. After Solly’s first birthday, we had moved from London to the US and assumed that a sibling would follow soon after. But as we were adjusting to our new life in California, my ovaries had clearly decided to pack up and retire to Florida because nothing was happening.

In what can only amount to a criminal conspiracy between mother nature and the patriarchy, it turns out that the single biggest factor affecting fertility is female age. It took several months of injecting performance-enhancers into my reproductive organs, $20,000 and two soul-crushing miscarriages to get us our longed-for second child. “My kids were a photofinish with the end of my fertility,” I wrote in the book I was working on at the time. A neat, happy ending to the sprawling pain of IVF.

Except that it wasn’t quite so simple.

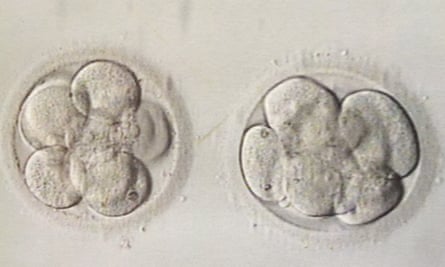

The final cycle of IVF had been a success. So much so that as well as giving us Zeph, it has also produced four surplus embryos, technically Zeph’s fraternal twins. According to protocol, the clinic had frozen these for potential later use. There was no way of knowing how many – if any – of these embryos were viable, but statistically for my age, two of them should be. And there they still are, nearly three years on, languishing in an industrial park in San Ramon, and calling to me with increasingly shrill urgency.

Our “frosties”, as the internet fertility forums like to call them, are part of a growing frozen embryo population. Although no central records are kept, it is estimated that there could be up to two million frozen human embryos stored across the globe. More are created from new IVF cycles every month.

In theory, a frozen embryo can last almost indefinitely and, as long as it is chromosomally normal, can be defrosted at any time in the future to make a baby. A patient at our clinic recently gave birth to a healthy boy from an embryo frozen 19 years previously by another couple. Even disregarding the sci-fi possibility that some future megalomaniac embryologist might defrost the entire population and conscript them into his slave army, neither the legal system nor our ethical landscape has quite caught up with the implications of this icebound human underworld.

Most clinics have a similar policy to ours – that they will store embryos until their owners either stop paying their storage bill (typically about £30 a month) or when the woman is 52. After that, the couple has the option to donate them to another family, hand them over to medical research or have them destroyed. But in reality, the legal implications for a clinic destroying embryos without express permission could be significant. There have already been court battles over embryo custody – women desperate for a last ditch chance at a baby fighting for the right to use them against their former partner’s wishes. Men fighting for the right not to become fathers against their will.

For the first year or so of Zeph’s life, I didn’t give much thought to his frozen siblings. But over time, the problem about what to do with them has become more acute.

Frozen at five days old, these embryos already have their entire genome in place.

The infinitely intricate coding that makes up a human being has already been locked down; it has been irrevocably determined not just if they are chromosomally normal and therefore viable, but also if they are male or female, dark haired or light. It is already decided whether they will have my wide, flat feet, or my husband’s bony shoulder blades, my sons’ curly hair or my mother’s ability to go for days on end with barely any sleep. Without any way of accessing these truths, all the possibilities co-exist in my mind.

My attachment to these frozen cell clusters is obviously vastly less than it is to an actual child. But over time, it has somehow settled into the same basic category of emotion. Every time I picture them I get a visceral jolt of maternal feeling. Sweethearts, you must be so cold in there without your coats. I am their mother.

In the world of IVF, even discussing a third child feels impossibly greedy, like agonising over whether to buy a third yacht at a food bank. But deep down, I have always yearned for three children. I came from a quiet, bookish two-child family and have always loved the slightly anarchic dynamic of three, the balance of the family just tipped in favour of young rather than old. One of those embryos could become another soft-cheeked toddler in pyjamas on the sofa, another person round the table at Christmas. Each represents a third higher chance that one of our children will visit us in our old age or give us grandchildren or marry someone we like.

Then again, each also represents a third more sick days and lunches to pack, a third more bone-aching exhaustion and heart-chilling worry and whining and tantrums and hours despairing while another small child refuses to put his shoes on.

Happiness researchers draw a distinction between “life satisfaction”, meaning the deeper overall assessment we make of our own wellbeing when taken in the abstract, and the more fickle moment-to-moment moods of our lived experience. The current thinking is that these two types of happiness work completely independently of each other and it is perfectly possible to have one without the other.

Perhaps nowhere is this paradox more apparent than in the realm of parenthood. There is no doubt in my mind that my children bring me the overarching deep kind of happiness, but some days, around 5pm, when I’m struggling to boil some pasta, with urgent child-need in piercing stereo, that happiness can sometimes feel as though it’s buried so deep it would need a specialist team of navy divers to locate it. Would a third child in our 40s stretch us to breaking point?

For a long time, the whole dilemma was a strange abstraction. We didn’t even know whether any of our embryos were viable and therefore able to even make a baby, so even discussing whether we wanted a third child felt like a moot point.

Then a few weeks ago, I came across an article about a relatively new series of procedures. The embryos could be thawed, tested and then refrozen. The tests would show us whether they were chromosomally normal and therefore able to create a live baby, and, as a byproduct, their sex. Previously, the only way of knowing this information would have been to transfer them to my uterus one by one and wait to see if they “stuck”, potentially risking four miscarriages or late-term terminations from unviable pregnancies – something I was deeply reluctant to go through.

The problem was, the testing itself carries a risk to the embryos. The procedure has about a 3% risk per embryo of causing irrevocable damage. By deciding to test them, we could potentially destroy them. It was agonising but, in the end, our hunger for information won out. Just a few days after we informed the clinic of our decision to go ahead, they defrosted, biopsied and refroze our embryos. The results would be back within five business days.

I spend the next week on shpilkes, as my Jewish family would say, that state of jangly nauseous anticipation, at the same time terrified, and not exactly sure what I was terrified of. I would veer wildly from full-scale Waltons fantasy (all four normal! Moving to the country with our six children!) to almost hoping that none would be viable, that the decision would be out of our hands and that all the past and future disappointments of IVF will be discharged in one single catch-all disappointment.

It wasn’t until about three minutes before close of business on Friday that my phone rang.

“Great news!” said Valerie, our nurse. I paused. I had got myself into such an emotional tangle, I was no longer quite sure exactly what great news would look like. Then she said it. “You have two normal embryos.”

And suddenly, for the first time in three years, I had emotional clarity. This was exactly what great news looked like, the answer I had hardly dared to hope for all along. “And …” She rifled through her papers. “All four are boys!”

So there we have it. In our childbearing years, my husband and I have produced a total of six boys. And two of them are there, healthy in the freezer, like little wartime evacuee children, gas masks slung over their shoulders, waiting at a country train station to be chosen.

In some ways, knowing this information has made it all harder. Of all the possible combinations, two boys has perhaps the greatest emotional resonance for me. I picture the freezer boys like our sons, waiting for us to come and rescue them with the same crumpled, anxious expressions they wear if I am ever five minutes late to pick them up from preschool.

Will we give one of these boys a shot at life? I think so. Even with normal embryos there are no guarantees that it will work. But I think we’ll regret it if we never try.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion