Over the next day or so, you may see headlines and reports about a “nightmare” “superbug” that has been detected for the first time in the US.

So far, the Washington Post reports:

“The superbug that doctors have been dreading just reached the U.S.”

And the article starts with: “For the first time, researchers have found a person in the United States carrying bacteria resistant to antibiotics of last resort.”

CNN had a similarly alarming but distinct headline:

“'Nightmare' drug-resistant bacteria CRE found in U.S. woman”

And NBC News ran:

“'Nightmare Bacteria' Superbug Found for First Time in U.S”

There are some truths and cause for concern here, but a lot of errors and hype as well. Let’s sort it out.

Here’s what really happened

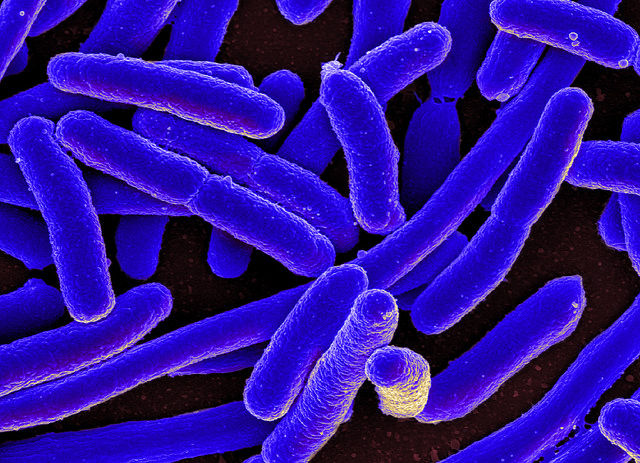

Researchers reported Thursday that a 49-year-old Pennsylvania woman was found to be infected with an E. coli strain that’s resistant to the last-resort antibiotic colistin. Upon DNA analysis, researchers determined that the E. coli is resistant to colistin because it carries a colistin resistance gene called mcr-1 on a circular piece of DNA called a plasmid. The study appears in the journal Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

As Ars previously reported, mcr-1 was first discovered in bacteria late last year in China. The discovery of the gene quickly raised concern because of its placement on a plasmid, which bacteria can easily share with their neighbors. Colistin resistance had been reported before in other bacteria—including in bacteria found in the US—but their colistin resistance genes resided on bacterial chromosomes, which aren’t shareable. Experts feared that the new plasmid-based colistin resistance would easily spread among bacteria, potentially to ones that are already resistant to other last-resort antibiotics.

Since the initial report, mcr-1-toting bacteria have been discovered on every continent. And the infected PA woman, who was suffering from a urinary tract infection, had not traveled in the last five months.

But this may or may not be concerning. It’s important to note that we don’t know exactly how long mcr-1 has been hanging around in bacteria or where it first came from. It may have spread around the globe in months or been lying low and spreading quietly for years. Either way, it was inevitable and expected that mcr-1-carrying bacteria would pop up in the US. (Although, in weeks of testing other bacteria from the Pennsylvania clinic where the patient was identified, no other mcr-1-carrying bacteria have been found.)

While concerns still stand, the alarmist headlines are unnecessary—and so are the errors.

Here’s what you can ignore

First, the “first” bit. The first line of the Post’s article states: “For the first time, researchers have found a person in the United States carrying bacteria resistant to antibiotics of last resort.”

Nope—this isn’t even close to true. This is absolutely not the first time a person in the US has been found with a bacteria resistant to a last-resort antibiotic. There are several last-resort antibiotics, and many bacteria over the years have shown up with resistance to them—including colistin.

For instance, way back in 1991, a hospital in Brooklyn suffered an outbreak of bacteria resistant to vancomycin, a last-resort antibiotic. In 2009, several Detroit medical centers suffered an outbreak of bacteria that were resistant to both colistin and carbapenem—another last resort antibiotic. And not even the National Institutes of Health has been immune to bacteria resistant to last-resort antibiotics. In 2011, an outbreak of carbapenem-resistant bacteria at the NIH’s clinic sickened 18, killing 11.

The only real first in this case is that it’s the first time mcr-1-based colistin resistance has shown up in a US patient.

While, again, this isn’t exactly good news, it’s not catastrophic. There are several last-resort antibiotics, and doctors can try different combinations and strengths of prescriptions before an infection may be deemed untreatable.

Next is the confusing CRE connection

The CNN headline, which has now been updated, initially incorrectly identified the colistin resistant bacteria as a CRE. Other articles have brought this term up as well.

CRE stands for carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. The Enterobacteriaceae are a big family of bacteria that include some harmless ones and some notable pathogenic ones, including Salmonella, E.coli, Klebsiella, and Shigella.

Carbapenem resistance is a big concern because it has been rising steadily in recent years, and CRE infections can lead to death 50 percent of the time. For this reason, CRE infections have been dubbed by some as “nightmare” cases.

However, the bacteria reported today is not a CRE. While it is an E. coli strain, it’s in the Enterobacteriaceae family and has a whopping 15 types of antibiotic resistance genes—genes for carbapenem resistance were not among them. There were several other antibiotics that the strain was still sensitive to as well.

Here's the quick take-away

Thursday’s report of a mcr-1-based colistin-resistant bacterial infection in a US patient is concerning, but unsurprising. The plasmid based resistant gene threatens to spread to other bacteria, potentially to ones that are already resistant to last resort drugs, such as CRE. However, the trajectory of mcr-1's emergence and its contribution to drug resistant infection trends is not yet clear. For now, the case serves mostly to highlight the ongoing crisis of rising antibiotic resistance and furthers the need for better stewardship of old antibiotics and development of new ones.

Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 2016. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.01103-16 (About DOIs).

reader comments

73