Job losses and precarious employment conditions have sparked such a sharp rise in suicides across regions hit by economic change that Australia may be “sleepwalking into a national disaster”, experts say.

On Tuesday suicide prevention organisations released electorate-by-electorate figures for suicide for the first time and called on political parties to pledge to address the problem.

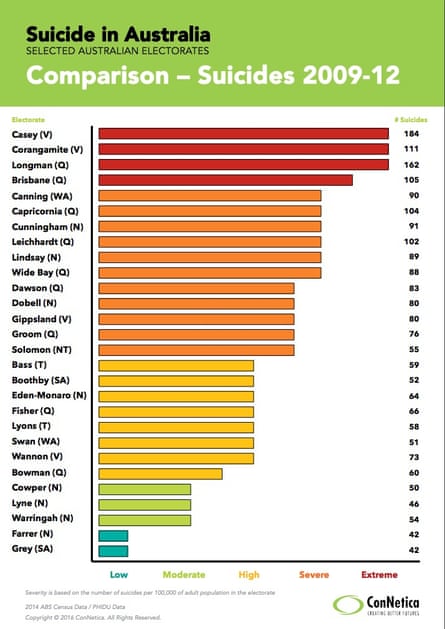

The electorates with the highest rates of suicide were Casey and Corangamite in Victoria, which had 184 and 111 suicides in the period 2009 to 2012, and Longman and Brisbane in Queensland, which had 162 and 105 suicides respectively.

The figures were compiled by the consultancy ConNetica from Australian Bureau of Statistics and Public Health Information Development Unit data.

Speaking at the launch on Tuesday the ConNetica director, John Mendoza, said “what we see in electorates like Canning, Capricornia, Corangamite and Cunningham is the impact of economic change”.

“Issues like the loss of manufacturing, the downturn in resource and construction industries, housing affordability and the high cost of education and retraining is hitting hard.”

Mendoza said a common characteristic of electorates with the most severe rates of suicide was the fact workers had lost jobs or terms and conditions.

“It’s what the literature refers to as precarious employment conditions – less certainty,” he said. “If you want to give people a mental health problem, if you want to raise their psychological distress, what do you do? Dose them up on uncertainty, dose them up on fear.

“That’s what causes mental illness, that’s what gets them to the point they see no other option but to take their own life.”

People who did not pass year 10 were most at risk because the transition into a new job or industry was harder without a higher level of education, he said.

Mendoza said: “We are in a steep trajectory in relation to suicide and self-harm and we are sleepwalking into a national disaster”.

Every year in Australia, about 65,000 people will attempt suicide and more than 2,500 people will die as a result. Suicide rates have increased by nearly 20% in the past decade.

Suicide prevention organisations asked politicians to sign a pledge that they will support the recommendations of the National Mental Health Commission to develop whole-of-community approaches to suicide prevention.

A co-director of Sydney University’s Brain and Mind Centre, Ian Hickie, said every region is different and, as health and hospital care are structured on a regional level, so should suicide prevention strategies.

Rod Little, co-chair of the National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples, said the issue of suicide had reached crisis point among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, citing cases of suicide by people as young 10.

Speaking in Angelsea in Corangamite on Tuesday, the prime minister, Malcolm Turnbull, described suicide as a national tragedy. He said his government was keenly aware of the issue of suicide and mental health, describing them as an economic and emotional drain on the nation.

In Canberra, Hickie said Turnbull had called him to emphasise the government’s commitment to regional approaches to suicide backed by new technological solutions.

“Get out of the national averages, get out of the non-specific approaches that do not work,” Hickie said. He also called for real-time data on suicide, as the most recent figures for suicide are from 2012.

Technology could be used to help prevent suicide by giving people access to mental health services out of hours.

“What does a young man at three in the morning who is suicidal in rural Western Australia actually do? Because I bet there won’t be a psychiatrist or GP within miles,” Hickie said. “That’s where technology is part of the solution.

“We expect the government to support the development of primary health network-led models, to select the areas of suicide prevention that matter.”

Primary health networks are regional centres that co-ordinate healthcare with general practitioners, primary and secondary care providers.

Hickie said Australians were disproportionately going to hospitals to get care because of “dysfunction within our primary care system, our out-of-hospital care systems”.

“Every parent I’ve spoken to about suicide and mental health care problems in the last decade ... tell me it is the out-of-hospital care that is either not there, or too infrequent, poorly defined, or ineffective that leads to deterioration in their son, daughter, spouse’s health and wellbeing, and in some cases tragically their loss of life,” he said.

The opposition spokeswoman on mental health, Katy Gallagher, said Labor had committed to the commission’s recommendation of a 50% suicide reduction target over the next 10 years.

She announced Labor would also commit to its recommendation to establish 12 suicide prevention pilot projects – including six in urban areas, four regional and two remote.