Elliott Johnson’s parents sit at their kitchen table, competing over memories. Even as a baby, Elliott couldn’t stop yabbering, says his mother, Alison. His father, Ray, smiles. “We almost christened him Yellalot rather than Elliott.” When Elliott was six, the local vicar visited his primary school and came away with one conclusion: the precocious lad with the opinions was going to be a politician. “He was saying words like palaeontologist. People would just look at him in amazement and think how can he say words like that?” Alison says. In his final year at primary school he edited a school newspaper and he had a column entitled Know It All Elliott. He was a know it all, but he wasn’t a smart arse, Ray says. Alison nods. “He’s always been very popular, and had lots of friends.”

We meet at their home in Wisbech, the beautiful market town in Cambridgeshire. Their detached three-storey Georgian town house sits on the northern bank of the river Nene. It’s only a few weeks since Elliott was found dead, aged 21. Their trauma is obvious – Alison is tearful, Ray’s hands are shaking. But they are determined to remember the best of their son. So they talk about the mock election held at school in 2010, alongside the general election. Elliott, who was in his final year of GCSEs and was one of three children, decided to stand as a Conservative candidate. Incredibly, he won more than 80% of the vote. “He received letters from Boris Johnson and Baroness Warsi congratulating him on the result,” Ray says. He pauses. “I think a lot of them voted for him just to get him off their backs, to be honest. I asked him how he managed to get over 80%, and he said it was because the others were lazy.”

Who was Elliott’s political hero? Ray, a retired businessman, looks a little embarrassed. “Maggie Thatcher, believe it or not. We’d debate politics.”

“You’d put him right on a few things wouldn’t you,” Alison says.

“Yes,” Ray says. “Sometimes I thought he was wrong, particularly some of the things with Thatcher.” Such as? “Well, I experienced her.” He laughs. “I used to work in the offices of British Steel in Corby, when they closed the offices down.”

Ray Johnson is short and stocky, a tough and kindly man. He says his son was even shorter than him – 5ft 4ins and skinny. But Elliott never let his size get the better of him. He played for the school rugby team, and more than made up for his lack of physical presence with his verbosity and style. “He didn’t want to be pushed into the corner or left in the shadows: he had to be in the forefront. He started to dress more eccentrically in sixth form. He’d wear waistcoats and a fob watch. He was very dapper.”

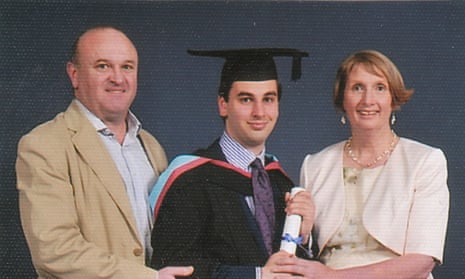

Sure enough Elliott Johnson did go into politics, just as the vicar had predicted. And his progress appeared to be seamless. Before he had finished his history degree at Nottingham University he was offered a full-time job as political editor of the rightwing Tory pressure group Conservative Way Forward. According to its website, CWF is a campaigning group founded in 1991 “to defend and build upon the achievements of our founding president Lady Margaret Thatcher”. CWF was relaunching, and had hopes of becoming the leading Conservative pressure group.

This was the job of Elliott’s dreams. He moved to London in June this year, and quickly began to make a name for himself with blogs that were opinionated, witty and sometimes bitchy. “It was probably the happiest period of his life,” Ray says.

Members of the local Conservative party told Ray they regarded Elliott as a potential prime minister. He laughs. “Whether that’s the case or not, I don’t know. I’d never have voted for him as prime minister because he’s far too strident for me.”

Final messages

On 15 September, just before 11pm, two police officers, one male, one female, knocked on the Johnsons’ door. Elliott had been found dead on a railway line in Sandy, Bedfordshire. He had been hit by a train. He had taken off his shoes, laid down on a towel and waited. The beloved fob watch, bought for his 18th birthday by his parents, had survived unscathed. On the front is an engraved portrait of Winston Churchill; on the back it says: “To Elliott on your 18th birthday, love Mum and Dad.”

Ray is struggling to control his breathing, and Alison is trying to hold back her tears. “And now we’ve got to pick the pieces up,” Ray says.

As soon as his parents were told of Elliott’s death, they asked the police to search the bedroom in the house he was sharing in Tooting, south London. “I knew he’d leave something for us,” Alison says. Sure enough, the police found three letters on his bed. One was addressed to “Ray and Alison”, another to friends and allies, and a third to “bullies and betrayers”. Elliott never called them Ray and Alison – it was always Mum and Dad. “I think that was his way of distancing himself from what he was doing,” Alison says. She shows me the letter. A despairing Elliott talks of his sense of failure – he says he has disappointed everybody by losing the money his parents had given him, losing his job, losing friends. But it made no sense to Ray Johnson. His boy had so many friends. And yes, he had been rubbish with money, but so were many students. As for being a failure, that seemed ridiculous to his parents.

Elliott had been made redundant a few weeks before he died. After only two months, his boss at Conservative Way Forward, Paul Abbott, had told him the organisation could not afford to keep on a full-time political editor; instead they would employ him part-time to look after social media. Yes, Ray says, his son had been in tears when he first told them about the redundancy, but the last time he and Alison had seen him, after his niece’s wedding and two days before he died, he had been in good spirits. He had told his parents things were fine, and that he had an interview lined up for a job with the high-profile political blog Guido Fawkes.

Alison directs me to the crucial paragraph in her son’s suicide letter. “I have also been involved in a huge political issue. I have been bullied by Mark Clarke and betrayed by Andre Walker. I had to wrongly turn my back on my friends. Now all my political bridges are burnt. Where can I even go from here? Even if I had done the right thing in my heart first and not been caught up in the fake idea of a rightwing movement. But that is that. I am sorry it has come to this.”

Even now, two months after their son’s death, Alison and Ray Johnson have not been able to unpick that paragraph . What they do know is that Mark Clarke is a prominent Conservative activist who started and led RoadTrip2015, a centralised campaign that involved bussing hundreds of young Conservatives around the country to canvas for candidates in marginal seats at the general election. Clarke, 38, was dubbed the Tatler Tory after the society magazine tipped him as a potential minister. Andre Walker, whom Elliott had accused of betraying him, was another political journalist – a close confidante of Clarke and somebody Elliott regarded as a close friend. Elliott had previously mentioned to his father that he had had a spat with a senior activist, but told him it was nothing to worry about.

To the friends and allies, Elliott wrote: “I let you down. Sorry.” To the bullies and betrayers he wrote “I could write a hate message, but actions speak louder than words. I was never one for hate anyway. But I think this should be on your mind.”

The recording

The day after Elliott’s death, Ray Johnson received a call from Paul Abbott at CWF, a man Elliott appears to have regarded as a friend and ally. Abbott told Johnson that he had received a short letter and memory stick in the post from Elliott, sent the day he killed himself. The letter was to the point. It read: “Dear Paul, make sure you listen! Apologies! Elliott xxx”

Abbott had listened to the recording, and asked Ray what he would like to do with it. Ray said he would like copies sent to both him and the police.

The memory stick contained a secret recording Elliott had made of a meeting with Clarke and Walker on 2 September, a couple of weeks before he killed himself.

In the recording, the two older men can be heard pressuring Elliott to withdraw a formal complaint he had made to Conservative party headquarters about an alleged bullying incident during a friend’s birthday party in a London pub, The Marquis of Granby, on 12 August.

In a formal letter of complaint he went on to write to the Conservative party, Elliott said Clarke publicly pinned him in his chair, hurled abuse at him and threatened to “squash him like an ant”.

Clarke had been angry about many things that night, not least being marginalised by CWF. Insiders say that when Elliott was involved with RoadTrip, Clarke would ask him to write blogs about characters within the Tory party, but Abbott had tried to put a stop to this once he started working for CWF.

Clarke criticised Elliott’s blogs and told him that neither he nor CWF were giving him sufficient respect. It seems that Elliott had become a pawn in a larger fight between Clarke (who had been Elliott’s boss at RoadTrip), and Abbott, who was now his boss at CWF. They appear to have fallen out over who got the top job at CWF, Clarke’s behaviour, and access to the young activists who might one day form the nucleus of a future Conservative government.

After the incident in the pub, Elliott raised it with CWF. A week later he received a “redundancy consultation” letter from Abbott. The letter states: “Further to your email exchange with our HR consultant, I was asked to review our operational requirements to establish your ways to limit your exposure to an external individual following an incident you described which occurred on 12th August 2015. As part of the exercise I have identified that there is a diminishing need for a dedicated political editor for CWF and therefore it is with regret that I write to notify you that your role is at risk of redundancy.”

In the recording of the meeting with Clarke and Walker, two weeks later, Elliott repeatedly asks for an apology, and Clarke repeatedly tells him that won’t happen. Clarke tells Elliott he went to visit the CWF’s chair, Donal Blaney, to tell him that Elliott was a risk to the organisation. CWF has always insisted that Clarke had nothing to do with the redundancy.

Clarke seems quiet and intimidating on the tape – making reference to the caution that Elliott had received at university for tweeting an election result before it was officially announced. The tweet was done in innocence, and was inconsequential, but Clarke was suggesting it could ruin any future career if people high up got to hear about it. Meanwhile, Andre Walker, Elliott’s supposed friend, sounds more overtly intimidating. He calls him “a fucking dickhead” and accuses him of disloyalty. “Do you know what happened to all the French in Vichy France?” he says. “They got shot. Do you want to be like the last Japanese soldier on the island after the war has ended?”

Ray and Alison Johnson were bewildered and distraught when they heard the recording. Yes, the bullying was awful, but Elliott was strong-minded and could stand up to anybody. He was more than capable of fighting back. And yes, he had been upset about losing his job, but already things were looking up. They suspected that something more was going on, that their son was somehow caught up in the middle of a larger battle within the Conservative party.

In the days following Elliott’s death, more and more allegations emerged about the behaviour of Clarke, a consultant with Unilever. About 25 people have made official complaints against Clarke over the past year, yet no official action was taken by the Conservative party until Clarke was suspended nine days after Elliott’s death and banned for life from the party last week. The complainants were largely young Tory activists who had been involved in RoadTrip2015 , which by then was regarded as a huge success. David Cameron was due to hold a reception that Clarke was invited to at Chequers in the autumn to celebrate the work of volunteers; this was later cancelled

Yet it has now emerged that the complaints against Clarke included allegations of sexual harassment, intimidation and plotting blackmail. Several sources allege that Clarke would find evidence of activists and politicians compromising themselves sexually or with illegal drugs, document it and then use it against them. This month allegations surfaced that he had attempted to blackmail the deputy chairman of the Conservative party, Robert Halfon, and the national chair of Conservative Future (the party’s youth movement), Alexandra Paterson, who were having an affair. Paterson, who until recently had been a close ally of Clarke, also claimed he had tried to blackmail her over drug-taking.

Clarke has strongly denied all allegations against him. In a statement, he said: “I have nothing further to add to my previous statements on Elliott Johnson as I am waiting to speak to the coroner. But I deny any wrongdoing.”

The sting

Tony, aged 20 and a friend of Elliott, made a complaint against Clarke after he allegedly harassed him and his girlfriend. Tony (not his real name) and his girlfriend were active in RoadTrip 2015. For a while, he says, the experience was positive. “We had a laugh when we were out after campaigning.” Was it a boozy culture? “Very, very boozy. It was always: ‘Right, we’re going to go to a pub and then a club.’ Weirdly, this was one of my main responsibilities. ‘We’ve got a road trip this weekend. Find us a pub and a good club.’” Who would tell him that? “Usually Mark or India Brummitt.”

Brummitt was a Commons aide to the Tory MP Claire Perry (who advises Cameron on how to curb the “sexualisation of children”) until she quit after reports that she and Clarke, who is married with two children, had sex on a pool table.

Was there a downside to RoadTrip? “It was always … I suppose sleazy is the word,” Tony says. “Mark would make inappropriate comments publicly.” Such as? “I was with an ex, we’d got together on RoadTrip, and he would always be commenting on our sex lives … Also there was big age gap between him and us.”

Clarke’s behaviour became more aggressive early this year, Tony says, and he claims Clarke made unwanted propositions to his then girlfriend. Tony is so upset, his sentences start to lose shape. He says he told her to go to the police, but she wouldn’t. He decided to distance himself from Clarke and RoadTrip. “I found a job and went thank you very much, bye. I cut all ties and haven’t spoken to him since.”

Five months later, in early September, Tony was befriended on Facebook by a French woman who had apparently taken a fancy to him. This is where things get embarrassing, he says. The wooing was quick and intense. “It was a matter of hours.” She then contacted him on Skype, stripped in front of him and persuaded him to perform a sex act. What Tony didn’t know was that he was being filmed. Soon afterwards he received, via Skype, a demand for €3,500, otherwise the film would be posted on Facebook. After Tony refused to pay the money, the video appeared on the website.

Now he is convinced that the “French woman” was actually Clarke, and that the strip was a pre-recorded video. Clarke denies this, and Tony has no evidence. Clarke has admitted that in the few minutes the video was on Facebook before being taken down, he got in touch with the Conservative party to tell them about it. He has since stated that he did this to protect Tony and others from blackmail. Tony laughs when I mention this. “Yeah! I fail to see how that is in my interests! When it was leaked, one of my friends was in touch with CCHQ [Conservative Campaign HQ] press office within 15-20 minutes of it going online. To which CCHQ press office said: ‘Yes, Mark’s already informed us.’ Now, hang on, he’s either stalking my Facebook very closely, which is bizarre, or he knew it was going up and was trying to brief against me.”

How did Tony feel about the sting? “I was pretty distraught. Pretty annoyed at myself for letting it happen to me.”

A couple of weeks after Tony’s humiliation, Elliott, a friend of his, killed himself. Tony was devastated – not least because he had known how Clarke had bullied Elliott. He had been at the birthday party in the Marquis of Granby where the initial incident took place, and a couple of mutual friends had helped Elliott write his letter of complaint. Finally, in late September, Tony made a complaint to the party.

Has all this changed his attitude to politics? “Like you wouldn’t believe,” he says. “I was so wrapped up in it. It becomes your entire life. You work in it, it’s your hobby, you’re doing it every weekend, and after the video came out and after Elliott’s death …” He trails off. “My girlfriend broke up with me because of the video. My life fell apart in the course of two weeks. And I thought, I don’t want to talk to any of these people again. I don’t want to have anything more to do with it all. These are horrible people wrapped up in their own thing … I don’t want to be part of this Machiavellian world where everybody …where you can’t say this or that, and you’re always on guard. I just don’t want to be part of that.”

Employed at the highest level

Nearly all of the allegations since Elliott’s death have focused on Clarke’s behaviour. Perhaps understandably so. This creates the impression that he was acting unilaterally, and on the outer edges of the party. In fact, he had been employed at the highest level by the Conservative party, and was reporting directly to the party’s joint chairman, Grant Shapps, who appointed him “director” of RoadTrip in July 2014. Responsibility for signing off the budget for RoadTrip was shared between Shapps, co-chairman Lord Feldman (now sole chairman), campaign manager Lynton Crosby (known as the “Australian rottweiller”) and deputy chairman Stephen Gilbert.

It was Shapps’ then head of staff, Paul Abbott, who recruited Clarke, a long-time ally, and in effect put him in charge of all the party’s young activists. After the election, Abbott was hired by Donal Blaney, the chair of Conservative Way Forward, as its chief executive. And it was Abbott who then went on to hire Elliott Johnson.

Since Elliott’s death CWF has put as much distance as possible between itself and Clarke. When I first spoke to Abbott in October he still sounded traumatised. No wonder. Abbott talked about Elliott with warmth – his sincerity, his style, his sense of humour. He said he was flattened by his death, but did not want to talk on the record.

Sources close to Abbott say he first heard of complaints about Clarke’s behaviour last year while working at CCHQ for Shapps, though he has always insisted those complaints were not as serious as later allegations against Clarke. After his move to CWF, friends say he tried to provide a safe haven for these youngsters and encouraged those allegedly bullied by Clarke to make official complaints to the Conservative party. He himself complained to the candidates department this year to try to ensure Clarke was never again allowed to stand for parliament. After Elliott’s death, CWF insiders say, he felt a degree of guilt for having failed to protect the 21-year-old, although he also regards himself as a whistleblower.

Meanwhile, Donal Blaney, the chairman of CWF, suggested to the Daily Mail in November that he was also a victim of Clarke. Blaney, described as “a close friend of several cabinet ministers”, told the Mail he had been physically threatened by Clarke. “He started effing and blinding at me over something trivial. I told him I would not put up with it. He went totally berserk. His temper goes from nought to 60 miles per hour in a second. It is very scary. It’s no wonder people, me included, feel intimidated by him.”

Blaney may well have felt intimidated by Clarke. But it is striking that those now voicing their concerns appear to have discovered Clarke’s alleged unpleasant side so recently.

The accusations

In 2007, when Clarke was chair of Conservative Future, the party’s youth wing, a female activist complained to CCHQ of alleged sexual harassment and bullying. A year later he went on to become the Conservative candidate for Tooting, south London. In 2008 a former girlfriend gave an interview at the time of the Conservative party conference in which she said he should never be allowed to stand for parliament because of his behaviour.David Cameron, then leader of the opposition, was said to be livid because the story dominated conference.

At the 2010 election, Clarke was beaten by Labour’s Sadiq Khan in Tooting. His campaign attracted bad publicity – there were allegations of bullying.

Sayeeda Warsi, a former Conservative party chair, was recently accused by the Bath MP Ben Howlett of having failed to take action after he complained to her about Clarke. Lady Warsi was surprised by the accusation, not least because after the 2010 election she established a candidates committee to rule on whether problematic candidates could stand again. Clarke was removed from the candidate list.

“During my time as chairman, Mark Clarke was never involved in any initiative that I was involved in, or in any campaigning. He was effectively persona non gratis, as far as I was concerned,” says Warsi. “He was always a disaster waiting to happen, and this was common knowledge.”

Warsi claims she was also subsequently a victim of Clarke’s bullying and Twitter trolling, when Clarke implied she was antisemitic. Warsi appears to have been one of a few people who stood up to Clarke. In January this year a local Tory party chairman tweeted that a speech she had made was “a diatribe against Israel and a pro-Hamas speech”. Clarke then tweeted: “So @SayeedaWarsi is now slagging off the Jewish Tory party chairman … who was offended by her speech.”

Warsi responded, tweeting at Clarke : “Bullying for silence.” In March she again replied to his trolling, asking: “[Is this] just one of your regular pathetic slurs!” Another time she wrote: “And a final word of advice @MrMarkClarke, to make your mark in politics focus on being principled rather than being a poodle :-).”

Warsi sent a letter dated 20 January to Grant Shapps, who had replaced her as Conservative chair in 2012, complaining about Clarke’s behaviour. “I raised my own concerns about Clarke with Grant Shapps and never received a satisfactory response.”

Warsi, who resigned as a foreign minister in 2014 because she found the government’s position on Gaza “morally indefensible”, wrote to Shapps saying: “It’s worth noting that until this moment neither I nor anyone else involved was aware of [the local party chairman’s] religion nor had any reference been made to ethnicity, race, religion. As a result of the above I received a number of abusive messages including accusations of antisemitism.” She concluded: “I look forward to hearing from you what action you intend to take against both [the local chairman] and Mr Clarke.”

The letter was ignored for two months, then Warsi received the following reply from Shapps, after Lady Stowell, leader of the House of Lords, had become involved. “I was sorry to hear from Tina [Stowell] that you’d not received a reply to your letter from earlier this year and wanted to get back to you, I appreciate you getting in touch and making me aware of the situation. I will be sure to raise this with the relevant individuals at CCHQ and look into the issue.” That was the first and last she heard about her complaint.

Back in the fold

Why were Shapps and Paul Abbott, his chief of staff, so keen to rehabilitate Clarke when he had been left out in the cold by the party for four years? An insider at CCHQ who worked in the chairman’s office at the time says: “Mark turned up in summer 2014 and says: ‘I’m organising all this stuff.’ His message was: ‘I’ve grown up, I’ve changed, I’ve had a kid, I’m married.’ He’s very capable of seeming like an ordinary, sensible human being, he’s got a proper job at Unilever, he’s in his late 30s, he’s capable of seeming like a normal person. He can be very seductive. He seduced Paul and Grant.”

Asked for comment, a Conservative spokesman, speaking on behalf of Shapps, said: “An investigation is currently under way and it is not appropriate until we can establish the facts.”

Abbott admits he received the first complaints about Clarke back in 2014. He insists he passed these on internally and that he has spent the past seven months trying to rid the Conservative party of Clarke. If this is true, why were the initial complaints not acted upon? Clarke was not only allowed to run RoadTrip until the general election, but had hopes of running RoadTrip 2020, setting up a company with that name. The party said a decision on this had not been agreed. Abbott recently admitted deleting thousands of emails while working at CCHQ – and said everybody dealing with the media was instructed to do the same.

Last week the Conservative party told the BBC it had been “checking and rechecking, but have not been able to find any records of complaints that were made but not dealt with” before it launched an investigation into Clarke in August. In a subsequent statement, released a day later, the party inserted the word “written” to say it was “unable to find any written complaints of bullying, harassment or any other inappropriate behaviour during this period that were not dealt with”. Leaving alone the activists, the party appears to have forgotten the written complaint made by Warsi in January. Alleged victims believe their complaints were destroyed or ignored.

A leaked email from Abbott to Clarke reveals that as late as this August he was discussing the complaints made against Clarke with him (“I’m afraid that I did have to do quite a lot of ‘corralling’ as well, even if you don’t remember it now! This included for example dealing with all the complaints made about roadtrip and your behaviour – from associations, young activists, MPs/candidates, and so forth. Of which, you are well aware.”)

It is unlikely that Donal Blaney, the chair of CWF, was unaware of some of the types of behaviour Clarke had used throughout his career. Blaney strenuously denies being aware of any alleged criminal wrongdoing by Clarke.

While Blaney has never stood for parliament, he has long had a finger in many political pies. He has taken a particular interest in the youth wings of the party because he believes today’s young Conservatives are tomorrow’s cabinet ministers.

In 2003 Blaney founded the Young Britons’ Foundation, a conservative training, education and research thinktank established to “help train tomorrow centre-right leaders and activists today”. YBF is proudly cross-party. Its executive director, Matthew Richardson, is also the party secretary of Ukip. Blaney has called YBF “a madrasa” that radicalises rightwing conservatives and embraces American-style “attack-dog” politics. YBF claims to have trained thousands of activists, taking them on trips to America where they met neo-conservative groups and visited a shooting range in Virginia to fire submachine guns and assault rifles.

Mark Clarke was mentored by Blaney and is very much a product of YBF. In fact, only last year Blaney, who has known Clarke for 15 years, presented him with the “Golden Dolphin” – according to the YBF website, “a special award … for those who merit particular admiration for their courage and leadership … this award is in the personal gift of YBF’s founder, Donal Blaney”. In recent weeks, Clarke’s name has been removed from the list of winners.

It seems that Clarke, Abbott and Blaney were close allies until recently. Several sources say it was only in the final run-up to this year’s election that a schism seemed to develop. For all Blaney’s admiration for the “courage and leadership” of Clarke, despite the fact both had been chair of Conservative Future (Blaney was the first chairman of the Conservative party’s youth movement, in 1998-99, and Clarke was chair from 2006-08) it was Abbott who was offered the top job at CWF, not Clarke. The pair appear to have fallen out. It was in this world of internecine political jockeying that Elliott Johnson found himself engulfed.

New culture

Sayeeda Warsi believes that when she stood down as party chair and was replaced by Grant Shapps in September 2012, the culture of YBF began to permeate Conservative Central Office. “There appeared to be the feeling that none of the chairman’s team should remain. I thought it was a huge mistake. They got rid of people who had huge corporate knowledge of CCHQ. I, for example, kept the same PA that the previous chairs Eric [Pickles) and Caroline [Spelman] had had. The first thing Grant did was get rid of her, but she had always been loyal to the office of the party chairman. The chief of staff was culled, deputy chief of staff was culled, the person who did third-party engagements was culled, the speech writer was culled, almost the whole team, and because of that the chairman’s office did leave themselves open to not having a great deal of corporate knowledge.”

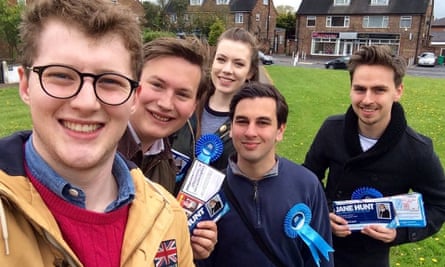

Under David Cameron, the Conservative party has become more and more centralised. And nowhere was this more apparent than in its general election campaign. Clarke’s RoadTrip was crucial because party membership had shrunk to less than 150,000, of whom few could be classed as activists and many were elderly. Anybody with the ability to mobilise members, particularly young ones, was an asset. And nobody knew how to mobilise young Tories in the way Mark Clarke did. But the new centralisation was widely criticised.

Ben Harris-Quinney, chair of the Bow Group, the country’s oldest conservative thinktank, wrote articles saying that party democracy was being undermined by centralisation. He claimed activists were being promised they would be added to the candidate list or given jobs as special advisers if they delivered enough leaflets, and that this undermined local democracy because the future Conservative elite was being drawn from a small group of Metropolitan HQ favourites.

He said RoadTrip 2015 was embarrassing – a bunch of kids bussed in from the south who often knew nothing about local issues – and suggested that the chairman of the Conservative party should be an elected post. At the same time, he was writing pieces about the alleged historical paedophile ring in the Tory party. This is when he heard from Mark Clarke. Harris-Quinney claims: “He said: ‘OK you’ve said your piece, but if you carry on there will be a lot of attacks against you and you won’t be able to pinpoint where they’re coming from so you won’t be able to respond.’”

Harris-Quinney had voted against same-sex marriage and had co-authored a paper for the Bow Group suggesting that in seats where the Conservatives couldn’t win, right-minded people should consider voting Ukip if the party had a chance of winning. He alleges that Clarke asked friends to pass on the message that if he didn’t stop making trouble he would face public claims that he was a racist homophobe. Clarke denies this.

He did not take what he claims was Clarke’s advice, and wrote a blog complaining about control freakery within the Conservative party. That, he claims, is when the harassment started. A few days later he received a legal letter on behalf of the Conservative party saying a small organisation he was involved with – Conservative Grassroots – was not to use the word Conservative with a capital ‘C’. He believes this was connected to his blog.

The more I look into the suicide of Elliott Johnson, the more young Conservative activists come to me with allegations of bullying that do not start or stop with Clarke. And there are many more claims that bullying took the form of smear campaigns and threatening legal letters.

Bullying appears to have been happening at all levels of the party, and was particularly prominent within Conservative Future. It often appeared that the bullied were also guilty of bullying. Last month, Conservative Future chair Alexandra Paterson’s affair with the Conservative party deputy chairman Robert Halfon was revealed. Yet until recently, when Paterson finally complained about Clarke, she was regarded as his candidate and somebody willing to act for him.

For a while it appears that Elliott Johnson, under pressure from Clarke, was sometimes acting under his instructions. In his early days as a blogger, when he was working on RoadTrip, if Clarke needed somebody praised or damned, he would call on Elliott. This seems to have been the case when Elliott posted an anonymous blog in January 2015 on his Facebook page credited to a website that he edited, called Right of Centre. The blog, which was not well received, was very critical of another activist at Conservative Future who he said was “widely accepted amongst Conservative Future circles as the worst ever officer of Conservative Future”. It has been widely reported that Clarke eventually bullied the activist into standing down.

Paterson, at 30 considerably older than most member of CF, wrote to members of Conservative Future on Facebook: “We are now in crisis. I need you all to like Elliott’s status immediately.”

One teenage activist replied: ‘Sorry, but I’m not going to do that. It’s a mean and spiteful post.”

Paterson responded: “You are young. I want to protect you. But I can’t if you don’t do this.”

“What difference does it make me liking a Facebook post I don’t agree with?” the activist asked.

“Everything,” said Paterson, who added: “Just wanted to update you on something. Elliott’s blog is sanctioned by me and Mark on all his pieces. Just bare [sic] that in mind before going forward. There are reasons we do things”

”That doesn’t mean we have to bully people,” the activist says.

She concludes the exchange by saying that if he contradicts her and Clarke, “it looks bad on me and Mark. He gets very angry.”

When asked about this incident, Paterson says: “This was another example of Mark Clarke using Elliott in an appalling way and bullying other activists. Elliott was very upset about the negative reaction which followed relating to this article. Mark Clarke saw the negative reaction and he bullied me into ‘asking’ people to like the status. I did this under extreme pressure.” Did she end up bullying activists? “No comment.”

In the end, it’s all about power, Harris-Quinney says. He believes Paterson did what Clarke wanted so he would support her bid to be chair of Conservative Future; Clarke and Abbott did what Shapps wanted because they wanted to be offered safe seats in parliament. Shapps was willing to use the services of Clarke because he believed a successful campaign would secure him a prominent cabinet position if the Conservatives won the election. As for Blaney, he appears to have been interested in mentoring young activists to cultivate contacts – many of today’s activists will be tomorrow’s MPs.

‘The fixer’

Elliott’s allegation of bullying was directed at Clarke. But what of Andre Walker, whom he accused of betrayal? Before Elliott got his job and moved to London, he would occasionally stay with Walker at his home in Windsor. Walker, in his 30s, is a lobby correspondent for a conservative blog. At times, it appears that Clarke regarded Walker as his fixer. On 9 April 2015, Clarke tweeted Walker saying: “At my signal, unleash hell. That could be the motto of our friendship!” In 2010 Walker was recorded plotting a smear campaign against Alison Knight, deputy leader of the Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead. He was made to resign from his job at the council.

After Elliott’s death, Walker made contact with the Johnson family and offered to tell the truth. He also posted the following statement on Facebook: “As journalist why don’t I just spend the day writing what really happened to Elliott Johnson. That’ll have the Tory leadership quaking in their boots!!!” He quickly took it down.

In mid-November he gets in touch, and insists again that the true story is very different from that being told. I ask what he means. Well, he says, he believes the pressure on Elliott was coming not from him and Clarke to withdraw his complaint, but from those in the party, including Blaney and Abbott, who wanted him to pursue it. He says he does not understand why Elliott said he had betrayed him in his suicide note. I tell him it seems obvious to me: Elliott considered him a close friend and yet at the meeting he recorded with Clarke, Walker bullied him unforgivably.

Yes, Walker says, that was unpleasant, but it was two weeks before Elliott died. Walker claims that he and Elliott did not fall out, and continued to be close until his death. He points to the trail of Facebook posts in the time between the incident in the pub when Clarke first intimidated Elliott, the recorded meeting with both Clarke and Walker, and Elliott’s death. Walker insists that the narrative becomes different when you see their exchanges, and sends screenshots of his Facebook page.

And it is surprising. While their relationship does not seem equal (Elliott appears to be very much the junior in the friendship – usually the first to get in touch, often left waiting for replies, possibly at Walker’s beck and call) it emerges that he and Walker were by and large on good terms right until his last post, the day before he killed himself.

Straight after Elliott was bullied in the Marquis of Granby by Clarke he is angry with Walker. On 13 August at 0.55am, Elliott writes: “I don’t want to speak to you for a while mate. You have totally betrayed my confidence. I thought we were working together for the movement to stop a problem. Turns out this was not the case. I am very upset as I had so much faith in you as a friend. If you read that letter I sent to you a few weeks ago I hope this obvious. Really disappointed this has happened. I value my close friends hugely.”

Later that morning, Walker tells him he has not been in touch because he’s been ill and offline. He writes: “By the way I have no idea what you are on about. But not speaking to me is fine because you are getting on my nerves going on about all this stuff. I’m bored of it!”

That is when Elliott tells him about his encounter with Clarke. “Mark pinned me (literally in a seat) last night and bullied and interrogated me over stupid crap. I tried to say as little as possible. But what he did say was that you were actually trying to get as much information off me as possible for him to have a go at us in CWF. I thought we were talking about helping out the movement in order to stop conflict not cause more. It’s really sad for me because I fully trusted you and thought you were genuinely interested in defending the rightwing movement. This shouldn’t be a CWF versus Mark Clarke thing IMO [in my opinion]. Mark says that I was just being used. I hope you get better soon.”

Walker replies: “Well that is rubbish, I will ask him why he said that but overall if someone wants to make stuff up I can only do so much to stop them.” Later that day Walker says: “I am so sorry you got cornered.”

They don’t communicate on Facebook for the following 12 days. In between, Elliott makes his formal complaint to CCHQ against Clarke, and Walker emails him saying: “I’m dealing with the issue you raised tonight as a matter of urgency. I think it is a very serious issue, perhaps more serious than you realise. Can I ask that you do not comment or engage in any further discussions about this. Instead refer everything to me.” When they do start talking again on Facebook, it appears that Elliott is keen to withdraw his complaint.

On 1 September, Elliott writes: “Hey Andre any chance of meeting up with you and Mark tomorrow. I hear he wants to apologise to me.” He sounds calm.

Four days later he writes to Walker: “We need to do that email.”

Walker responds instantly with a draft letter for Elliott to send to CCHQ saying he wants to drop the complaint. “Okay I will write it on here now. Dear X, As you know I recently made a complaint about Mark Clarke that you intend to meet me to investigate. Having had time to reflect on the issue I have decided that a formal complaint through the Conservative Party is not the best way to deal with it. As such I see no reason for us to meet, as this would be a waste of time for you. Thanks for all your help nonetheless. Regards …”

That day Elliott sends an email withdrawing his complaint, and in the evening he receives a terse response from Simon Mort, who is heading up an internal Conservative party investigation into complaints against Clarke.

Mort writes: “I take your point. However having sent a two-page complaint to the party chairman and already occupied some considerable part of his and my time with this, you have put these facts into the debate along with information provided by many other people. Therefore I believe that you should have the courtesy to meet me for 20 minutes. You and I can then discuss whether it should go forward as a formal complaint or not. I look forward to seeing you at 4 Matthew Parker Street [CCHQ] at 11am on Monday. Please confirm that you will be there. Simon.”

Elliott sends it to Walker for advice. Walker tells him “Say no. I’ll draft a response.”

But by now Elliott is concerned that he is damaging himself reputationally by withdrawing the complaint. He writes to Walker: “I’m very worried about what I will be thought of by the central Conservative party.”

Walker replies: “Don’t worry about it. It’s no big deal.”

Elliott says: “It is when you have no job atm [at the moment] yes I think we should discuss this tomorrow … The way that email is written makes it unacceptable for me not to attend.”

The next day, he writes to Walker: “Going to be leaving for Richmond shortly are you wanting me to stay over at your house.” But Walker fails to turn up. Elliott is upset with him, and writes at 5.33pm: “I believe I will go to this meeting tomorrow but will withdraw my complaint in person. I believe CCHQ will have a go if I do not turn up. Its best to be firm and polite on the matter. Again call me if you have a better idea.”

An hour later he receives the following message from Mort: “I trust most earnestly that I am going to see you at Matthew Parker Street 11am tomorrow because 1) I have fixed to come up to London to continue this investigation and your component is just part of a bigger mosaic involving other people [and] 2) Even if you do decide that a formal complaint is not appropriate, I still need more information to explain to several very senior members of the party, who have absorbed your submission, why you have come to this position. I keenly look forward to seeing you. Simon.”

Elliott writes to Walker: “I feel i must go and argue for no further action on my part. Not going will get myself and mark into further trouble …”

A while later he adds: “Obviously I’ve not received a message from you. I will thus send an email to Simon Mort stating I will be there as I don’t want to upset people at CCHQ. This is a meeting to decide whether to go further I will argue for it to be not. I also do not believe I have been forced into that position by anyone. I have also told Mark this is my position.”

It is impossible to pinpoint the reason for Elliott being so keen to withdraw the complaint. What is clear is that Elliott is now also feeling pressure from the Conservative party not to withdraw the complaint. Conservative Way Forward has admitted it was also applying pressure on him not to withdraw the complaint.

Elliott appears relieved after meeting Mort. “I went to the meeting and everything is now cleared. Anything to do with my issue has been dropped. I also sang Mark’s praises when asked about RoadTrip in general,” he writes to Walker. “They also said had I not gone they would have taken what I wrote as exactly my word on what happened in the Mog [Marquis of Granby]. I significantly played down what happened.”

For the next week he appears happy. He is grateful to Walker for any help with trying to get a job, and laughing at his jokes. “Thanks for meeting me and agreeing to book a meeting with Guido,” he writes on 10 September.

This is consistent with his parents’ account of his final week. They talk about Elliott’s optimism, how happy he was at the family wedding, how confident he was that he could get a job with Guido Fawkes.

Then on the day before he apparently kills himself, he hears something that upsets him. For the first time in more than a month he mentions betrayal in his posts to Walker. “[Alexandra] Paterson is talking about some sort of betrayal with me have you or Mark been speaking to her obviously I don’t mean in general but about me.”

But his mood is still positive. At lunchtime he speaks to Walker. Elliott says: “By the way have you spoken to Guido and arranged a meeting yet. Thanks for doing this btw.” Then at 5pm he tells Walker of a meeting held at the Wilson Room in parliament’s Portcullis House and asks if Walker fancies going.

This is their final exchange.

EJ: “You going to go as it is so close.”

AW: “I’m in Da Vindsor!”

EJ: “Lol. Not then. Never mind.”

AW: “‘Da Vindzor’ is what our Pakistani friends call Windsor lol.”

EJ: “Lol.”

That evening, according to friends Elliott was happy. He took the tube home with Alexandra Paterson; they sat together and chatted until they got off at Tooting.

“Earlier that night we know he handed a letter to Alexandra Paterson,” Ray Johnson says. “And the letter started with: ‘I am very upset to hear that you will not speak to me. I do not know why this is.’ He asks why she isn’t speaking to him, and admits to her: ‘I have also been involved with a CCHQ complaint against Mark Clarke. I was told to keep this secret at the time, but my part in the wide complaint against Mark is over now.’” Paterson, who had finally turned against her mentor Mark Clarke and had also made a formal complaint, is believed to have been angry that Elliott had withdrawn his. After Elliott’s death, Paterson told Ray Johnson they had resolved their issues that evening. “After he handed me this letter, Elliott and I spent a few hours together where he explained what had been happening with Mark,” she said in a letter to Ray Johnson. “I assured him that I was not angry at him and hugged him before he left.”

Paterson told the Guardian this week that he walked her home and hugged her on her doorstep.

Friends of Elliott say he believed that Clarke was due to talk to CCHQ about the complaints against him the following day.

Ray Johnson would love to know what happened that final day. All he knows is that as soon as his son got home, late at night, he started to look up methods of suicide and researching locations. The next day, 15 September, Elliott went to Sandy railway station, took off his shoes, lay the towel on the tracks, and waited.

Party crisis

In the two months since Elliott’s death the Conservative party has been in crisis, as story after shocking story about Clarke and others have emerged.

Not surprisingly, key players in the party have been keen to stress how little time they had for Clarke. Not least Abbott, Blaney and deputy chairman Robert Halfon. “Clarke is an appalling man and I wish I had never met him,” declared Abbott. In another statement, eerily echoing Abbott’s, Halfon declared: “He [Clarke] is appalling and I wish I had never met him.”

Shortly before Clarke was thrown out of the Conservative party, Blaney said: “Mark Clarke is a menace. I find it surprising, to say the least, that two months after his appalling treatment of Elliott came to light, he is still a member of the Conservative party. The party must show that it will not tolerate this kind of behaviour.”

This week he told the Guardian: “Like so many others who had dealings with Mark Clarke, I wish I had done more to stand up to him and I am sorry that I did not.” Blaney and Abbott regard themselves as whistleblowers, saying if they had not encouraged people to make official complaints about Clarke he would still be running RoadTrip.

But the alleged victims of Clarke find it hard to feel much sympathy. They point out that, two months after Halfon claims he was first blackmailed in May, he tweeted to Clarke and the Conservative party: “What an honour to officially launch Road Trip 2020”; that Abbott brought Clarke back to work for CCHQ despite his previous behaviour resulting in his removal from the candidate list in 2010; and that only a year ago Blaney had presented Clarke with the lifetime achievement award at his Young Britons’ Foundation conference. Blaney say: “Like so many others who had dealings with Mark Clarke, I wish I had done more to stand up to him and him I am sorry that I did not. All I can do now is ensure that lessons are learned and nothing like this ever happens again.”

Meanwhile, the two joint chairmen at the time of the election, Grant Shapps and Lord Feldman (now the sole chairman) are not publicly taking any responsibility for failing to act earlier over Clarke. Feldman claims he first heard of the allegations of bullying in August. If this is true, Ray Johnson says, he should be sacked for incompetence because the latest batch of complaints against Clarke go back to August 2014.

As for the party’s internal inquiry into the death of Elliott Johnson and the behaviour of Mark Clarke, that has already been labelled a whitewash – presided over by Edward Legarde, a Conservative-supporting judge who is said to have ambitions of becoming a Tory MP.

David Cameron has somehow managed to remain at arm’s length from the scandal that has engulfed his party.

Back in Wisbech, Elliott’s parents are struggling to make sense of their son’s death. Yes, they say, he suffered depression when he was 16. “But he had had no problems since then. He has been so happy in recent years,” Ray Johnson says.

An inquest into Elliott’s death is to be held in the new year, for which the British Transport police are compiling a dossier of evidence for the coroner. It is understood the force has started to interview a number of those involved.

We may never know what finally pushed Elliott Johnson over the edge. But it does seem he felt cornered – by Clarke, who wanted him to withdraw his complaint, and by those at Conservative Way Forward and head office who pressured him to go ahead with it. Lady Warsi believes that the tragic death of Elliott Johnson reflects a broader problem at the heart of politics. “It can be a nasty, ruthless world. I was shocked at how the sort of conduct you thought had stopped in school you saw all over again. I experienced behaviour that would be unacceptable in any other sphere. The childishness, the name-calling, the bullying, making people feel isolated, the briefing, the reputational damage. It’s unhealthy and it puts good people off entering politics.”

Ray Johnson admits his family is finding things tough. On 16 November he sends me a link to the then new story that Halfon had allegedly been targeted for blackmail by Clarke over an affair. “Some nights we can’t sleep,” he writes. The email is sent at 3.46am. A week later he tells me that the previous night Alison was rushed to hospital. Thankfully, it turns out not to be the heart attack they initially feared, but the doctors believe her condition is stress-related.

Ray is determined to get to the heart of the destructive culture within the Conservative party, which he believes to be at least partly responsible for his son’s death. He thinks Elliott didn’t know who to turn to or whom he could trust. When we first speak in October, he says: “I think he decided in that final letter to the bullies that actions speak louder than words. He decided he was going to do what he was going to do to himself, but he was going to do it in such a way that he was going to bring Clarke down.”

By late November he has come to the conclusion that Elliott wanted to do more than that – he wanted to expose all the bullies within the ranks, and possibly bring down the whole party. He believes that there should be an investigation into whether anyone has committed criminal offences. He also believes the Conservative party has failed in its duty of care to Elliott and others because they allowed Mark Clarke to run RoadTrip, aware of his history. “The only thing that is keeping us going is the fight for justice,” Ray Johnson says. “And that means exposing all those responsible for putting Clarke in a position of power.”

Additional reporting: Jamie Grierson.

In the UK, the Samaritans can be contacted on 116 123.