Inspiration meets innovation at Brandweek, the ultimate marketing experience. Join industry luminaries, rising talent and strategic experts in Phoenix, Arizona this September 23–26 to assess challenges, develop solutions and create new pathways for growth. Register early to save.

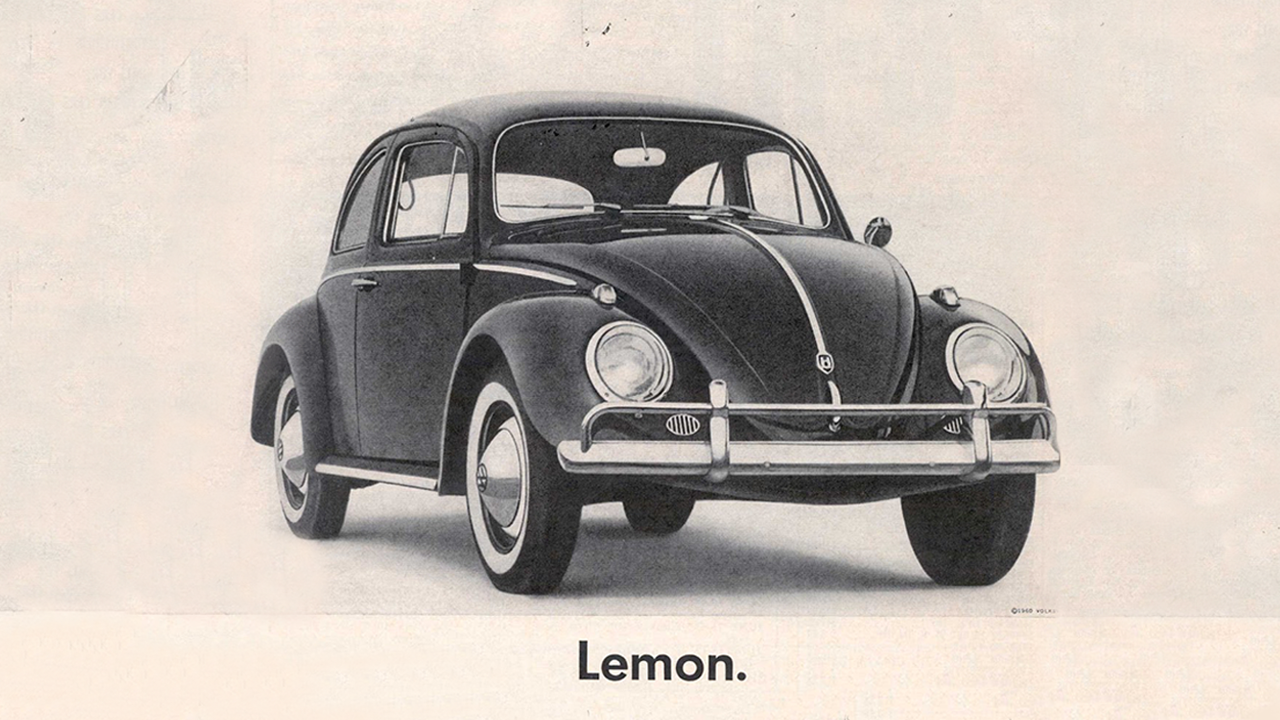

"This Volkswagen missed the boat. The chrome strip on the glove compartment is blemished and must be replaced. Chances are you wouldn't have noticed it; inspector Kurt Kroner did."

In 1960, Volkswagen ran what may have been its most famous ad ever: Lemon. The one-word headline described a 1961 Beetle that would never make it to a dealer. It had a mere blemish, enough for VW engineer Kurt Kroner to reject the vehicle and inspire Julian Koenig, the DDB copywriter partnered with legendary art director Helmut Krone, to pen the famous ad.

The copy mentions 159 checkpoints and a willingness to say "no" to cars that don't cut it. It concludes with the argument that Volkswagens maintain their value better than other automobiles.

"This preoccupation with detail means the VW lasts longer and requires less maintenance, by and large, than other cars," the ad reads. "It also means a VW depreciates less than any other car. We pluck the lemons; you get the plums."

That ad, along with the rest of DDB's first VW campaign, launched the industry's creative revolution. It changed advertising forever. It also introduced America to what would become one of the most loved and respected brands of all time: a brand that stood for quality, honesty, and a commitment to its customers; a brand—not a company or a product—worth many, many millions of dollars.

As recently as 2014, VW carried a goodwill valuation of $23 billion on its balance sheet. While goodwill is an intangible asset (it represents the difference between a company's hard assets—cash, plants and equipment, and inventory—and its market value, which is typically assessed when a company is sold), it's an important one, for it suggests the value of the brand: all the thoughts, beliefs and expectations that come to mind when someone sees the logo or hears the name. Put another way, it's a measurement of trust.

If VW had no cars, no dealers, no factories, what would its name be worth? That's goodwill.

In Volkswagen's case a lot of that $23 billion came from advertising. In the 1960s and beyond, DDB gave us dozens of brilliant executions. In the early aughts, Arnold launched the charming "Driver's Wanted" campaign, re-introducing the Bug and promising the masses the joy of affordable German engineering. More recently, Deutsch has made us smile and continue our love for the brand with ads like The Force, making us feel good about the cars and the people who drive them.

Sadly, however, we no longer feel that way about the people who make them.

In recent weeks, it's been revealed that VW broke the law and deceived its employees, its dealers and its customers. Its heinous act—concealing the obscene level of emissions in its diesel models with a sensor and software that conveys phony data—makes us wonder whether we can trust any of the sensors and software in their cars. Do we really need new brakes a few days after our warranty expires?

I've owned a few VWs in my lifetime. I bought them as much for the advertising as for the cars. VW's advertising made me feel good about the brand, the car and myself.

And like anyone who has ever worked in the advertising industry, I've admired the work and even been jealous of the agencies and creatives who made it.

Today, however, I feel sorry for them. They may not have been hurt as badly as customers who've seen the value of their cars plummet or the dealers who are likely to endure some rough times, but they too have lost something.

Like goodwill, it may be intangible, but whatever sense of pride and accomplishment marketers feel for having been part of VW's advertising legacy has been blemished—like the glove box on the 1961 VW Bug.

Too bad Kurt Kroner wasn't still around.

Edward Boches (@edwardboches) is a professor of advertising at Boston University, a former partner/CCO at Mullen and a frequent contributor to Adweek. This article originally appeared on his blog.