The Red-Baiting of Lena Horne

At the height of her career, the beautiful young performer accidentally stumbled into a power struggle between Hollywood communists and McCarthyites.

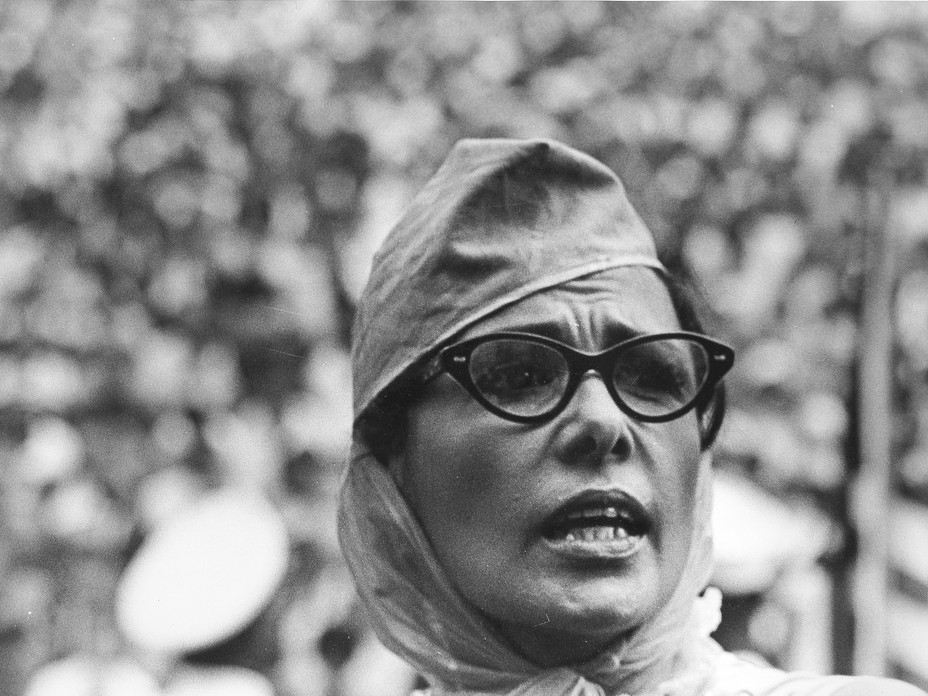

She was a goddess with a honey-sweet voice. “I remember once seeing her on a train,” says the jazz scholar and author Stanley Crouch. “She had a luminous restrained presence that most superstars try to pretend they have. She really had it.”

Over the course of her long life, Lena Horne became a star of film, music, television, and stage, as well as a formidable force for civil rights. She won a Tony in 1981, and two years later, earned an NAACP medal that had previously been awarded to Martin Luther King, Jr., Richard Wright, Langston Hughes, and Rosa Parks. When she died in 2010 at age 92, President Barack Obama noted that she was the first black singer to tour with an all-white band and that she refused to perform for segregated audiences. “Michelle and I join all Americans in appreciating the joy she brought to our lives and the progress she forged for our country,” he said.

Yet there was a brief period in the early 1950s when Horne’s career seemed to be over. Her name had appeared in Red Channels, a report that listed more than 100 entertainers who appeared to have communist leanings. For more than three years after that, she struggled to get work. She continued to perform at nightclubs, but nobody in the TV or film industries would hire her.

She was at a low point in June 1953 when she performed at the Sands Hotel in Las Vegas. The city was not the shining epicenter of entertainment that it is today. It was not even the Las Vegas of Frank Sinatra’s famed Rat Pack yet. There were only a handful of hotels and motels, and the infamous Strip was nonexistent. But Horne had few other options. She closed the show with “Stormy Weather,” her most famous song:

Life is bare

Gloom and misery everywhere

Stormy weather

Just can’t get my poor self together

I’m weary all the time

Then she walked off the stage and went back to her room. On Sands stationery stamped with the hotel motto “A Place in the Sun,” her story unfolded. “Dear Mr. Brewer,” her letter began.

For decades, Horne’s biographers have largely glossed over the question of how Horne found her way back into the entertainment business. Even Horne’s daughter, Gail Lumet Buckley, who wrote a 1986 book about the Horne family, didn’t get to see the letter until 2013. All that time, it was sitting in a bankers’ box, packed away in a children’s playhouse on a dusty ranch in the San Fernando Valley. But those 12 neatly written pages reveal how a beautiful young black woman became a pawn in the Cold War—and how she ultimately regained control of her career and her life.

From the beginning, Horne was troubled by her inability to fit in anywhere. She refused to play the maid and prostitute roles usually reserved for black actresses of her time, which narrowed her prospects in Hollywood. At the same time, many black artists accused her of using her lighter skin to “pass.” Horne herself was ambivalent about her looks. “I came from one of the First Families of Brooklyn,” she once said, “yet it was the rape of slave women by their masters which accounted for our white blood, which, in turn, made us Negro ‘society.’”

In 1941 when she was 23, Horne was hired to perform at a unique club in Greenwich Village called Cafe Society Downtown. It was a “people’s nightclub,” wrote Buckley, Horne’s daughter, in her 1986 book, The Hornes: An American Family, the only place in the city where the races mixed.

What few of the patrons knew was that the club was moving money for the Communist Party. They were distracted by the musicians and mesmerized by Horne’s beauty. She was learning to personify everything she sang, and to make eye contact with the audience, especially men. In November 1941, Harper’s Bazaar called her the queen of Cafe Society. She later said that most of what she knew about music she absorbed there.

One night after Horne’s show, the 43-year-old black stage and film star Paul Robeson came to her dressing room to pay his respects. His six-foot-three stature matched his voice—a baritone so commanding that he was the main draw of one of the most successful musicals of all time, Show Boat, where he debuted his signature tune, “Ol’ Man River.”

Robeson had an affinity for Horne because her grandmother, a staunch character with a college education, had helped him get a scholarship to Rutgers. He’d gone on to Columbia Law School—an astonishing rise for a man whose father had been a runaway slave. As a performer, Robeson had seen the world, including the Soviet Union where he was treated like royalty and squired around the country. During the 1930s, he’d even enrolled his only child, 9-year-old Paul Jr., in an exclusive school in Moscow, where he’d studied with Stalin’s daughter, Svetlana.

On this particular night in 1941, Horne found herself seeking Robeson’s advice. As she later detailed in her letter at the Sands Hotel, she told him she was exhausted by the pressures of show business, the racism she faced from the white establishment, and the disdain she heard from black people who accused her of “trying to pass.” Robeson kept listening. Finally, he exhorted her to devote her life to making the country a better place, to eradicate her pain by helping people everywhere. He named specific groups such as the Council for African Affairs and the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee.

Horne later said she was unfamiliar with these organizations at the time, but she took Robeson’s advice and signed up. She knew the country was still in the Great Depression and the world seemed to be growing closer to war. And with the rise of Hitler in Europe, Robeson’s call to actively oppose fascism felt timely. But she didn’t know that Robeson was part of something much larger, that his dedication and passion came from a force he didn’t discuss in the open, even with a kindred spirit like Horne.

“We were usually secret, covert, manipulative—it was part of the air we breathed. We said, ‘We have causes and we want to work with other people to do this, and this, and this...’” George Moore trailed off as he spoke, recalling his time in the communist orbit. His father, Hollywood writer Sam Moore, had been a member of the Communist Party, and George had been active in the youth wing throughout high school and college. In interviews, Moore and a half-dozen other Hollywood ex-communists said that the approach Robeson used with Horne was familiar. Celebrities were advantageous to their cause because they could dress up something most Americans would reject if presented outright, the ex-communists said. The most votes the Communist Party had ever received in a presidential election, a little more than 100,000, had come in 1932, during the depths of the Great Depression.

In the post-war era, the communists’ challenge was how to get people like Horne working for them. Party members were taught to identify the grievances of potential recruits and offer them a vision of a utopia where those problems didn’t exist. Subtlety was vital. And Marx, Lenin, or communism itself could never be mentioned. “Too risky,” says Moore. If the communists could capture Horne, her glamour would come with the bonus of an issue the Soviets also believed they could turn to their advantage: bigotry.

By the early 1940s, Walter White, the leader of the NAACP, was embarrassed that the two most successful blacks in film, Hattie McDaniel and Lincoln Perry, were reduced to playing maids and a character named Stepin Fetchit—“The Laziest Man in the World.” White believed Horne was going to transform the image of black America and prodded Hollywood executives to give her auditions.

She got parts after that, but none of them were leads. In one MGM musical after another, she showed up in small roles—musical interludes that had little to do with the main story. In some states, where theaters couldn’t show black performers, her scenes were edited out altogether. “No one bothered to put me in a movie where I talked to anybody, where some thread of the story might be broken if I were cut,” she said in a 1957 interview. “I had no communication with anybody. I began to feel depressed about it, wasted emotionally.”

Yet the songs were modern, captivating, even racy. “You’ll never catch her whipping up spoon bread and spirituals in an Aunt Jemima rig—she’s nobody’s mammy,” wrote Liberty, a general-interest weekly magazine popular in the ’40s. During the war, she traveled with the USO to perform for the troops. When the military excluded black servicemen from one concert, Horne stayed longer and did a separate show just for them. In return, black soldiers wrote to MGM and thanked the studio for giving them their own pin-up girl. “A lot of places where they were, they couldn’t put Betty Grable’s picture in there, see, but they were safe with my picture,” Horne said years later. “They made my career.”

In 1944, Horne won the Motion Picture Unity Award for “outstanding colored actress of the year.” But no matter how much admiration Horne received, she still didn’t feel worthy, as she would later reflect. She was the perfect mark for Carlton Moss, a 34-year-old black screenwriter who was on the speakers’ platform at the awards gala and invited her to perform on his radio show, Jubilee.

In contrast to Robeson’s giant presence, Moss was unassuming, with an almost nerdy voice. But when Horne began to confide her insecurities, he responded the same way Robeson had: He suggested that she channel her frustrations and insecurities into activism. In particular, he urged her to join the Hollywood chapter of an organization called the Independent Citizens Committee of the Arts, Sciences, and Professions, which had been founded to advance President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s liberal agenda. She agreed.

The group’s leaders elected Horne to the Citizens Committee’s executive board where she served with movie stars such as Humphrey Bogart, Bette Davis, Olivia de Havilland, and, for a short time, even Ronald Reagan. Her commitment grew and she was made one of the Citizens Committee’s vice-chairmen. As Time reported in a September 9, 1946, story about the Citizens Committee, “Lena Horne will sing at any rally.”

With celebrities like Horne on the stage, the organization drew as many as 20,000 supporters to its events. But what most of those people, including the notables at the top, didn’t know was that a core group of Communist Party members was taking control of the prominent Hollywood branch, what de Havilland described to me as a “nucleus.” Carlton Moss was one of them.

The New Leader, a now-defunct magazine founded by socialists, once estimated that a small cadre of Communist Party members controlled an estimated 70 national organizations and thousands of local groups in 1946 alone. In Hollywood, multiple sources confirm, there were only about 300 party members, but by using thousands of others who didn’t know the first thing about Karl Marx, that minority was able to dominate and control almost a dozen unions and guilds in the motion-picture industry, including screenwriters, story analysts, cartoonists, and painters.

After FDR’s death and the end of World War II, the Citizens’ Committee grew bolder, more critical of President Harry S. Truman’s Cold War policies. De Havilland, who served with Horne as a vice-chairman, once told me the total lack of criticism of the Soviet Union was a clue that the organization was under Communist Party control. As Horne became a regular onstage presence at the group’s events, including an affair opposing Secretary of State’s James Byrnes’s “Get Tough with Russia” program, Liberty called her the “feminine counterpart of Paul Robeson.”

It’s impossible to know for sure whether Horne had any inkling that there was something unusual behind her new friends. If she did, it’s not hard to understand why she chose to look the other way. After all, their social circles had allure and advantages. Suddenly the once lonely pin-up girl was running with scientists, authors, and academics. Buckley, Horne’s daughter, claimed in her 1986 book on the family that her mother knew “perfectly well that communists were active in many of the causes she supported.” As Buckley put it, Horne “never felt she was aiding communism, she felt that communism was aiding her.”

Moss stayed close to Horne throughout it all. When segregationists in L.A. banded together and filed suit to evict Horne from her house in Nichols Canyon by using restrictive covenant laws, Moss and other secret party members mobilized a campaign to support her. The celebrities outmuscled the bigots: Horne remained in her house and her ties to Moss grew even stronger.

By the spring of 1946, Horne was accepting an award from the New Masses Dinner Committee and speaking at a meeting honoring the Soviet writer Konstantin Simonov, sponsored by the Hollywood Writers Mobilization. Interviews with and testimonies from scores of ex-communists confirm that this organization and this affair were carefully designed to draw people like Horne to the communist cause.

At the time, there was only a trickle of revelations about Soviet spies in the U.S. and the American public was still unaware of the depth of the violent atrocities Stalin was inflicting upon the Russian people. Senator Joseph McCarthy’s scurrilous anti-communist crusade had not yet begun. So as Horne continued to praise outspoken advocates and screenwriters, she almost certainly didn’t think about the consequences—even if she did suspect that all of them were working in the communist underground.

She was only 32, but Carlton Moss still advised her that he thought it was time for her to write an autobiography. He suggested himself as her ghostwriter, and she took him up on his offer.

Horne trusted Moss so completely that she allowed him to read a draft of her autobiography to several of her friends before she’d read it herself. The overall theme of the book was the bigotry she had suffered. But according to Buckley, Horne thought Moss’s account of her life was “phony” and grew irate as she listened.

Moss went back to Horne and begged her to let him try again, explaining that he’d poured so much energy into her book that it had cost him other employment. After he showed her rewrites of the initial chapters, she authorized him to keep going but instructed him not to publish anything until she’d approved the final draft.

All this time, collective memories of the Soviet Union as a wartime ally were fading fast. Stalin had swallowed Poland, Bulgaria, Romania, and Yugoslavia; anti-communist fervor was starting to boil. The world looked a lot different than it had when Horne first responded to Robeson’s overtures. Newspapers teemed with headlines about communist spies stealing U.S. nuclear secrets, and by August 1949 the Soviets were testing their first atom bomb, named “Joe-1” in honor of Stalin.

De Havilland and Reagan began to suspect that the Citizens Committee to which they and Horne belonged was controlled by communists. De Havilland devised a plan to “smoke them out,” as she explained to me. She asked Reagan to write a resolution condemning both fascism and communism, which she then introduced at a meeting. The communists rejected it, and de Havilland and Reagan resigned from the organization. De Havilland then receded from the political fervor of the times, while Reagan was galvanized and joined forces with others in Hollywood to respond to the battle the Reds were waging in the entertainment unions.

But Horne stayed and was left standing with the communists.

In Washington, the House Committee on Un-American Activities launched investigations and high-profile hearings on communism in the motion-picture industry. Horne performed at a fundraiser for 10 screenwriters who’d refused to testify; they’d been fired from their studios and found guilty of contempt of Congress. After the Supreme Court refused to hear their appeal, all of them went to prison, serving sentences that ranged from six months to a year.

Meanwhile, Paul Robeson’s public stature began to crumble. Long regarded as a champion of African American causes, he was now just as effusive when it came to the Soviet Union. But he went too far for much of the public on April 20, 1949, when he appeared at the World Peace Conference in Paris, one of a series of prominent Soviet propaganda gatherings. Robeson declared that black Americans would refuse to fight for the U.S. if war broke out with the Soviet Union. “It is certainly unthinkable for myself and the Negro people to go to war in the interests of those who have oppressed us for generations,” he said in a speech. The next morning, the headline “Negros Won’t Fight Russia, Robeson Says” appeared in the Los Angeles Times, and the story was picked up in papers worldwide.

For several years, racists had been claiming that blacks were welcoming toward communism and lazy during World War II (even though during the war, half a million blacks had served in Europe alone). Many African American leaders objected to Robeson’s statement because it played into both slurs. In his 1949 testimony before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, Lester B. Granger, the executive director of the National Urban League, responded directly to Robeson’s statement:

Authentic Negro leadership in this country finds itself confronted by two enemies on opposite sides. One enemy is the communist who seeks to destroy the democratic ideal and practice which constitute the Negro’s sole hope of eventual victory in his fight for equal citizenship. The other enemy is that American racist who perverts and corrupts the democratic concept into a debased philosophy of life. In opposing one enemy, Negro leadership must be careful not to give aid and comfort to the other.

Jackie Robinson, Major League Baseball’s first black player, spoke for many blacks when he called Robeson’s statement “silly.” “I understand that there are some few Negroes who are members of the Communist Party,” he said, “and in the event of war with Russia they’d probably act just as any other communist would.”

Robeson didn’t seem prepared for the condemnation his Paris statement provoked from other blacks, but his outbursts continued. At Paul Jr.’s wedding to a white woman that June in New York, he exploded at reporters who were there to cover it. “This marriage would not have caused any excitement in the Soviet Union,” he said. “I have the greatest contempt for the democratic press, and there is something within me which keeps me from breaking your cameras over your heads.”

Things worsened for Robeson when Manning Johnson, a 10-year veteran of the Communist Party who was also black, identified Robeson as a long-time comrade. “There is not one iota of doubt about Robeson’s membership,” Johnson said. Johnson, who had rejected communism after serving as one of the party’s national leaders, testified to Congress on July 14, 1949, that Robeson’s assignment was recruitment. “They just wanted to use him, as a great artist, to impress other artists and intellectuals generally,” he said.

Johnson made a series of sensational claims. He said that Robeson had made it his goal to become “a black Stalin” for the Negro community. He also alleged that one of the party’s additional goals was to establish, as The New York Times reported, “a Negro communist republic, starting on the Eastern Shore of Maryland and reaching into the Deep South, which would declare its autonomy and put on a rebellion.” In 1955, Attorney General Herbert Brownell Jr. disclosed that the Department of Justice was paying Johnson (and dozens of other ex-communists) to expose Party members. Brownell told reporters that the government paid Johnson $9,096 in 1954, or $80,000 in today’s money. But even though the testimony came from a paid informant sharing fanciful schemes, it did lasting damage to Robeson’s reputation.

Horne said nothing to distance herself from Robeson.

In the spring of 1950, Horne set sail for Paris for a European performance tour. Lennie Hayton, a musical director from MGM, accompanied her in a professional capacity. He was also her husband, but interracial marriage was still illegal in California and the couple had been keeping their relationship a secret. When members of the press had asked her about the relationship, she’d lied to them.

While Horne was singing for European audiences, American network executives and advertising agents were reading about her in Red Channels, the Report of Communist Influence in Radio and Television—a 213-page booklet published by the retired FBI agent Theodore C. Kirkpatrick. He’d collected and printed data from public records on more than 100 individuals in film and TV. Several pages were devoted to Horne.

A short time later, Moss—with the help of another writer named Helen Arstein—finished Horne’s autobiography. It was more than 500 pages long, and Horne later claimed that he sent the manuscript to the publisher without showing her a word of it. The final product—In Person: Lena Horne, As Told to Helen Arstein and Carlton Moss—was released before she returned to the U.S.

In Person didn’t explicitly make Horne sound like a communist. But it had her paying tribute to the now-radioactive Robeson. At times, she seemed to suggest that America’s racial issues were a failure of democracy itself. In one scene, she arrives at a train station in Washington, D.C., for a performance at Howard Theatre. Horne and the musicians try to catch a taxi but are rejected by the driver:

“I can’t take you,” he said. “You’ll have to go over there and get one of them colored cabs.” Without a word, we picked up our bags and trudged out of the station in the direction of his gesture. There the colored cabs were permitted to drop their passengers and pick up new ones. We kept out silence until a colored driver picked us up. Then one of the musicians said in an odd tone, “And they call this the seat of democracy.” Everybody laughed. Everybody, that is, except me.

The book delved into Horne’s secret marriage to Hayton, disclosing her personal feelings about the relationship. Almost as soon as Horne’s ship docked in New York, reporters began firing off questions. They wanted to know about her ties to Robeson, her marriage to a white man—everything.

“My mother was furious,” Buckley, Horne’s daughter, told me in an email. “She hated the book.”

Horne first confronted Moss over the phone, but their conversation made her even angrier. When Horne returned to Los Angeles and met Moss face-to-face, she explained all the reasons she was appalled. Moss told her there was nothing she could do about it.

By 1951, dozens of whistleblowers had come forward to testify at the McCarthy hearings. In April 1951, the literary agent Meta Reis Rosenberg told Congress why she’d chosen to leave the party after seven years of membership. She said, “the minute you disagree, they begin to call you names, and this is a form of intimidation, this is a form of fear.” As part of her decision to break ranks, she identified members of her cell. One of the names she offered was Carlton Moss.

Meanwhile, black journalists were connecting the dots of Horne’s involvement with the party—the speeches, dinners, rallies, and other affairs. Her inclusion in Red Channels “shocked millions of her admirers,” reported the Los Angeles Sentinel, a leading African-American newspaper. Editors there published a scathing editorial, “An Idol Has Fallen,” lambasting Horne as “deplorable.” They wrote that her actions “do little to promote the Negro cause.” Writers at the Afro-American speculated whether Horne would become a “parallel to Paul Robeson, now the forgotten man of Hollywood” and asked, “Will Lena be replaced by the younger, beautiful and talented Dorothy Dandridge? She could be the person to make Hollywood forget Lena Horne.”

“Lena was screwed,” says Moore. “Nobody could or would defend her.”

By now, the mere hint that a celebrity might be a communist was enough to end her career. Nationwide boycotts were being organized against films connected with communists, and in an effort to protect their investments, executives and producers refused to hire people with communist connections. In that kind of climate, how could Lena Horne survive?

Horne tried seeking help from George Sokolsky, an influential New York Herald-Tribune columnist who had worked as a newspaper editor in Russia but now championed Joe McCarthy. Horne later said that Sokolsky expressed sympathy for her plight but didn’t offer to help her in any way.

Next, she sought the aid of Ed Sullivan. She’d appeared on his show in the fall of 1951, but the CBS switchboard had immediately started lighting up as viewers demanded, Get that communist off the air. Sullivan was the host who’d helped give Horne her initial wave of national TV exposure, and he also had a newspaper column in which he expressed anti-communist views. He listened to her plight and suggested she repudiate communism in a statement for Kirkpatrick, the Red Channels publisher.

She did, and Sullivan published that statement in his column on October 26, 1951. “No minority group in the country within the past ten years has made the advances scored by the Negroes … and we would have made even greater advances if the communists didn’t deliberately try to confuse the issue and stir agitation,” he quoted Horne as saying. She distanced herself from Robeson: “He does not speak for the American Negro. Agitation, however, will always be with us.”

The statement didn’t help her. Horne’s words were viewed as a calculated attempt at saving what was left of her career, and she’d sidestepped the larger issue of how she’d ended up in that grim place. Even with the wide circulation of Sullivan’s column, networks and advertisers wanted nothing more to do with Horne.

She had one other option: appealing to Roy Brewer, the toughest anti-communist in Hollywood. When an entertainer had been named in Red Channels, his or her only hope of working again was often to write Brewer a letter—naming names and disavowing communist connections in emphatic terms. If he found it sincere, he would forward it on to the studios. “Most of these people were the victims of the communists; they are not communists,” he later told Daily Variety. “We had to find ways for the ones who were suckered into it to get out. That was my effort.”

As a liberal himself, an international representative of the stagehands’ union in the ’40s and ’50s, Brewer told me he was appalled by the way the communists were appealing to people’s frustrations, ambitions, and idealism. These people didn’t necessarily know the communists were using them, he said. But when their ties were exposed, the public immediately labeled them as sympathizers. Brewer understood how they were being exploited by the covert members of the Communist Party.

Ex-communist screenwriter Richard Collins said the party cast Brewer as a Red-baiter, and historians and commentators picked up on it. According to an early script, this is how Brewer will be portrayed in the upcoming film Trumbo, which focuses on the travails of the communist screenwriter whom Horne had once praised.

By the time I met Brewer in 2001, he was retired and eager to tell his side of the story. It helped that he’d kept just about every document that crossed his desk. These papers were scattered about in more than 60 file boxes packed away at his daughter’s nearby ranch house. Over the next few years, he began to make them available to me.

When Brewer received his first call from Lena Horne on November 8, 1952, it was four days after Adlai Stevenson lost the presidential election. Brewer had been alarmed to learn that Horne was scheduled to perform at a Los Angeles campaign rally. He’d urged the rally’s organizers to remove Horne from the program, but her performance had gone on as planned. Brewer told me he hated McCarthy for damaging legitimate leftist causes, purchasing TV and radio airtime to accuse Stevenson of sympathizing with the Reds. But he also knew that the public was increasingly seeing the Democrats as soft on communism. That was indeed one of the main takeaways after Stevenson’s defeat.

Brewer told me his initial conversation with Horne lasted about 45 minutes. She seemed exhausted, hurt, and angry, venting her sense of betrayal, and Brewer told her she wasn’t alone. He said he knew of many cases where the Communist Party had surrounded entertainers, leaving them trapped. He told her she would have to clear her own name but pledged to support her.

However, he ended up doing more than that. On November 13, 1952, Brewer wrote to CBS and NBC executives, sending them a copy of the Ed Sullivan column with Horne’s 1951 anti-communist statement. “I have investigated this situation and I am of the firm opinion that there should be no further question about her position in this matter,” he wrote. “I am sending you this letter because I understand there is a possibility of the question being raised.”

A few days later, a CBS vice president wrote back to Brewer. The letter would be helpful, he said, in “removing any cloud that may have restricted the use of Miss Horne’s services.” On December 2, 1952, Brewer replied, “I think it is our duty to assist persons who have been innocently involved and who want to find a proper way to make known their real feelings.” That same day, Brewer informed Horne’s agent of the CBS communication.

But despite Brewer’s private attempts to help restore confidence in Horne’s reputation, her involvement with Moss continued to dog her. Moss’s coauthor on the Horne autobiography, Helen Arstein, was now vocal in her support of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. As the Rosenbergs were awaiting execution for stealing nuclear secrets for the Soviets, Arstein rallied a group to protest at the Truman White House. Horne knew that with Arstein’s name also now prominently linked to hers, she had to act.

So in June 1953, at Brewer’s urging, Horne sat down in the Sands hotel and wrote the letter she hoped would finally clear her name. “Dear Mr. Brewer,” she began. “If at anytime I have said or done anything that might have been construed as being sympathetic toward communism, I hope the following will help to refute this misconception.”

She went on to recount her betrayal by Moss: “I suddenly realized that I had been used by someone cold bloodedly, one who had no scruples about my bearing the responsibilities of his actions.” Horne stopped short of claiming that Moss had influenced her to sympathize with communism, but she wrote that a man he’d introduced her to had hinted it would be a good idea for her to join the party. She’d declined the invitation.

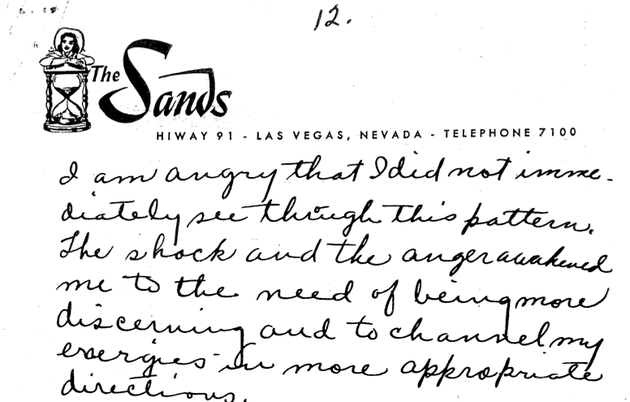

Horne also claimed that both Moss and Robeson had preyed upon her concern for “the Negro people” who didn’t have the same opportunities she did. Looking back on her friendship with Moss, she wrote, “I also realized that the many actions I had assumed under his influence were all a part of the same pattern. I am angry that I did not immediately see through this pattern. The shock and the anger awakened me to the need of being more discerning and to channel my energies in more appropriate directions.”

Horne continued, “I have always known that America offers the greatest chance to all people, to achieve human dignity—and since this terrible experience I am more determined than ever to do what I can to impress these principles on the thinking of all people I come in contact with.”

She signed the letter, “Most sincerely, Lena Horne.”

An excerpt from the final page of Horne’s letter to Brewer

Between the November 1952 phone conversation, Horne’s 12-page mea culpa, and Brewer’s own familiarity with the communist tactics Horne described, he was convinced of Horne’s sincerity. He rejected the charge that Horne was, as one associate of the publisher of Red Channels put it to Brewer in a letter, “above all a political person” who “let her hair down” when “there was no economic penalty for pro-communist activity.”

Brewer found the letter compelling enough that he sent it to at least nine of the top executives at studios and networks, places he thought would hire Horne if her communist ties weren’t an issue. He also mailed Horne’s letter to powerful political operatives, including Sokolsky, who had his secretary mail a copy to J. Edgar Hoover’s assistant on July 21, 1953. “I find it very interesting,” the assistant replied to Sokolsky a week later. (A copy of that reply is in the bureau’s file on Horne.)

This strategy proved far more effective than Sullivan’s more public help had. Brewer said he knew the public had grown cynical about attempts to clear celebrity’s names. “Their clearance is really a fix and nobody is buying it,” Red Channels’ Kirkpatrick had told Brewer in December 1952. For that reason, Brewer said, he kept his communications private, knowing that his messages would reverberate through Hollywood, New York, and McCarthyite circles.

Before long, Horne was back on CBS, appearing on hits such as Your Show of Shows and What’s My Line? At the Waldorf Astoria a couple years later, her concert was recorded by RCA and became one of the biggest-selling records in the label’s history. By the end of the decade, she was on Broadway starring in Jamaica, a musical produced just for her that became a smash hit. Her success carried on without interruption for the next 30 years.

Robeson suffered a different fate. He had become such a Soviet loyalist that in 1952, the USSR had awarded him the Stalin Peace Prize and the State Department had revoked his passport, stating that it wasn’t in the country’s best interests for him to travel overseas. He was able to get his passport restored in 1958 and visited Moscow in 1961. According to his biographer, Martin Duberman, he was confronted by Russians who pleaded with him to help their loved ones who’d been jailed and even murdered by the Soviet regime. During that trip, he attempted suicide by slicing his wrists; his son later told Duberman that his father was consumed by fears of the CIA.

Robeson later left for London, where he continued to be despondent. A friend and confidante told Duberman she found him in a fetal position one day and persuaded him to go to a psychiatric hospital for treatment. On the way there, they passed the Soviet Embassy and Robeson grew terrified that his friend was taking him there instead. “You don’t know what you’re doing, you don’t know what you’re doing!” she remembered him shouting. She said that Robeson was behaving as though “great danger was at hand”; while they were in the car, he implored her to “get down!” He lived the rest of his life as a recluse and died at age 77 in 1976.

As for Moss, his career faded. He ended up making instructional films like Happy Teeth, Healthy Smile and spent his final years working out of an office next to a Russian-language newspaper on Fairfax. When he died in 1997 at the age of 88, his New York Times obituary called him a “hero” and attributed his downfall to Hollywood’s enduring racism, not Moss’s association with communism.

Horne recovered her career and reputation, and was eventually honored by the NAACP. She was widely known for her unwillingness to stay silent in the presence of bigotry. The Los Angeles Mirror News described a February 1960 incident at the Luau Restaurant in Beverly Hills. According to the report, Horne heard a white man talking about her and declaring that he didn’t like “niggers.” Horne responded, “I can hear you and I want you to stop making those insulting remarks. After all, this is America and you cannot insult people like that.”

The man repeated the slur, this time louder. Horne got up and hurled a lamp, dishes, and an ashtray at him. The ashtray struck the man on his forehead and police were called in. “I lost control,” Horne told the paper. Other news outlets also covered the story: “Lena Horne Defends Race; Tosses Dishes at Man,” read the headline in the Las Vegas Sun. Later, as the civil-rights era was starting, Horne sided with Malcolm X over Martin Luther King, Jr.

She did, however, soften her stance toward Robeson later in life. In 1985, she accepted an award named in his honor from Actors Equity. By then, Robeson’s reputation had been largely rehabilitated: The Vietnam War had led to a widespread a critique of Cold War policy, and the media began looking more favorably on once-blacklisted Hollywood communists. At the awards ceremony, Horne declared that Robeson had helped her learn who she was.

That self-knowledge was never more evident than when she starred in her one-woman Broadway show, Lena Horne: The Lady and Her Music, in 1981. When she reached “Stormy Weather,” she introduced it with a prologue: “It’s taken me 40-some-odd years to grow comfortable with this song. My skin has grown around it. And no matter where it came from or how I got it, I’m allowed to sing it the way I feel.” And then she sang the words she’d performed more than 2,500 times in a career that spanned six decades:

All I do is pray the Lord above will

Let me walk in the sun once more.