‘A Mark of Pride, Not Shame’: Momentum and challenges in the ethical supply chain movement, two years after the Rana Plaza tragedy

In the minds of global consumers, labels on products originating from the Global South trigger images of sweatshops, child labour and unscrupulous owners poorly paying their workers. Nowhere was this image more starkly illustrated than in the Rana Plaza tragedy, two years ago today, in which more than 1,130 workers were killed and 2,515 injured when an eight-story garment factory in the outskirts of Dhaka collapsed. It later emerged that the workers there were being paid a pittance, and that on the day of the disaster, managers had compelled reluctant workers to enter the building despite major cracks in the complex’s walls.

The tragedy added new urgency to a movement that had been growing for the past decade, to force major brands to consider the ethical practices of their sourcing. The backlash from Rana Plaza and other disasters has boosted the fair trade movement, which has long advocated for fair working conditions and compensation for disadvantaged producers. The movement’s growth has led to a new form of branding in which various fair trade producers and certification organizations place their labels on products that meet their standards.

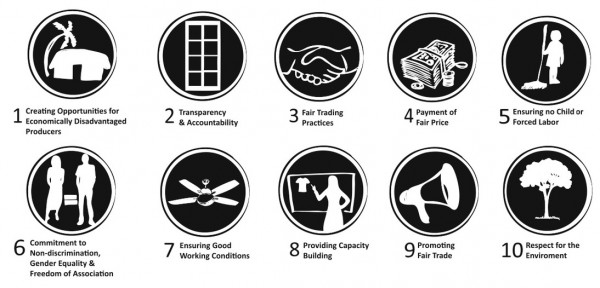

Often, consumers simply equate fair trade standards to payment of fair wages. However, the movement’s goals go far beyond putting a few extra dollars in the pockets of producers to ensure their sustainability. These goals also include ensuring that producers engage in democratic decision-making processes and that they follow basic environmental, health, safety, labour and human rights regulations.

Above: Principles of fair trade (Illustration: Global Village Peoria)

Aarong, a BRAC social enterprise and one of Bangladesh’s largest fashion retail chains, built sustainability and fair trade principles into its original business plan over 35 years ago. Its producers receive design input, instant payment for their goods, marketing and retailing support, amongst other livelihood developmental support. In return, Aarong insists that the producer groups maintain good working conditions, fair employment practices and respect for the environment – all principles of fair trade. The real challenge in the model becomes monitoring compliance to these principles; this is where innovation and social auditing is required.

Social auditing is the practice of evaluating a business’s ability to fulfill the economic, legal and ethical responsibilities expected of it by its stakeholders. Many social auditing firms have strong tools designed for monitoring large-scale, ready-made garments (RMG) factories. International brands are able to mitigate the risk in their supply chains by engaging these agencies. However, this has left behind the millions of workers in micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) that have little to no institutional support to hire auditing firms to monitor their well-being.

Compared to larger factories, individual MSMEs naturally have a significantly smaller number of workers. But when combined, much like Aarong’s supply chain of various producers, they can have just as many as their larger counterparts. As a pioneer in social auditing for MSMEs, Aarong has streamlined the auditing process through its own technologically driven monitoring system. Through annual audits conducted through SourceTrace, an Android-based application, even the most remote production units can be provided the support they require to sustain a safe and environmentally friendly working environment. Being able to centrally analyse their conditions with real-time data makes it much more efficient to provide the necessary consultation to these enterprises. But though there is no one-size-fits-all solution for all producers in lower-tech sectors such as handicrafts, providing social auditing through low-cost mobile applications can increase awareness of work conditions among both businesses and consumers, in spite of geographical barriers.

Today’s more socially conscious consumers demand to be connected directly to the producer, and to know that what they are buying is coming from a fair-trade conscious company. Entering into this new type of ”social contract” allows them to enjoy high-quality goods at affordable prices, while ensuring that the most marginalised producers receive a fair share of the economic prosperity that globalisation has brought. As BRAC chairperson Sir Fazle Hasan Abed mentioned in his New York Times op-ed following the collapse of Rana Plaza two years ago, “Made in Bangladesh should be a mark of pride, not shame.” Through continued synergy and prioritising social compliance, the government, private sector, NGOs and consumer groups can work to reverse the stigma associated with Global South producers, and prevent tragedies like Rana Plaza from happening in the future.

Editor’s note: This post was adapted from an article originally posted on the BRAC Blog.

Tanvir Hossain is the manager of marketing and sustainability at Aarong.

- Categories

- Environment