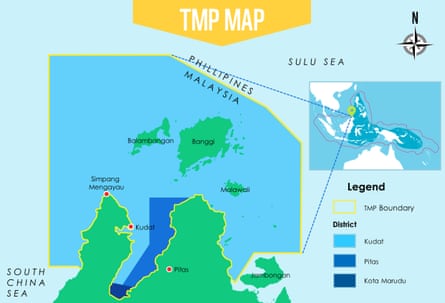

Malaysia has just established the biggest marine protected area (MPA) in the country. The Tun Mustapha park (TMP) occupies 1m hectares (2.47m acres) of seascape off the northern tip of Sabah province in Borneo, a region containing the second largest concentration of coral reefs in Malaysia as well as other important habitats like mangroves, sea grass beds and productive fishing grounds.

It is also home to scores of thousands of people who depend on its resources – from artisanal fishing communities to the commercial fisheries sector – making it in many ways a microcosm of the entire Coral Triangle bioregion, where environmental protection must be balanced with the needs of growing coastal populations.

It’s taken nearly 13 years of consultation, strategic planning and negotiation to get the new Tun Mustapha MPA officially gazetted, thanks to its sheer size and the complexity of developing an action plan that could satisfy local and commercial interests in an ecologically sustainable way.

The park is pioneering a mixed-use approach to marine conservation, where local communities and the fishing industry can continue to fish in designated zones they themselves have helped select in consultation with Malaysia’s Sabah Parks department and NGOs including the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), which has helped spearhead the project. This is vital in a fishery that generate around 100 tonnes of catch per day.

Overfishing, blast fishing and the use of sodium cyanide to capture high value reef species like Grouper for the Live Reef Fish for Food Trade have had a major impact on the ecosystems off northern Sabah, which are home to 250 species of hard corals and around 360 species of fish as well as endangered green turtles and dugongs.

In September 2012, a research team comprising 30 marine scientists and volunteers found that around 57% of the reefs analysed were in excellent or good condition. But the researchers also found abundant evidence of negative human impacts, including blast fishing (a total of 15 bombs were heard during the trip), overfishing and pollution. Iconic species like sharks and turtles were conspicuously absent; when megafauna such as these are missing, it indicates that an ecosystem is under pressure.

The data confirmed the urgent need for a sustainable management approach to preserve existing biodiversity and to allow depleted fish stocks and damaged coral to recover. Areas with minimal damage can recover in as little as three to five years, according to WWF Malaysia. Areas with more significant damage will require longer – five to ten years or more.

“The establishment of Tun Mustapha park will boost the conservation and biodiversity of this uniquely rich natural environment,” said Marco Lambertini, Director General of WWF International. “The park’s gazettement should act as a model and an inspiration for marine conservation in the Coral Triangle and worldwide,” he added.

Tun Mustapha has huge and as yet largely untapped potential for nature based tourism development. Besides diving, the area is replete with beautiful white sand beaches, pretty islands (more than 50 in all) and stunning seascapes. There are a number of key turtle nesting areas, offering opportunities for “voluntourism.”

The challenge now is to try and make it all work. As the Coral Triangle and reefs around the world face unprecedented levels of coral bleaching and plummeting fish stocks, effective, replicable marine management models that work for both people and ecosystems will be critical.