Law and Crime

The Degenerate Anthropophaginian

Noted author offers appetite-suppressing study of famous American cannibal.

Posted September 2, 2015

Some years back, I coauthored a book with James Starrs, A Voice for the Dead. Our first chapter opened with the exhumation of the five alleged victims of Alferd/Alfred Packer, the so-called Colorado Cannibal, the Macabre Man-Eater, or as a female historian back in the day dubbed him, "The Great American Anthropophaginian.”

Did he or didn’t he murder his companions for their meat and their dough? That’s the question.

“The Alfred Packer case,” Starrs explains, “is one that intrigued me over a long period of time as a teacher in a course in criminal law, because I always wondered why he, as recorded, alleged that he acted in self-defense when he might have alleged that he acted out of necessity. I wanted to find out what the truth of the matter was, so I went down to Lake City, Colorado.”

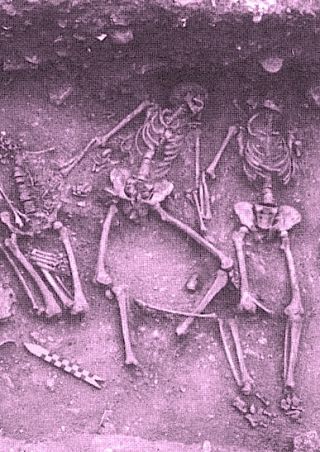

He focused on the exhumation, believing that modern forensic science might answer the vexing questions that surround the case.

Professor Harold Schechter, on the other hand, delves deeply into the actual story for his latest book, Man-Eater. Known for his series of serial killer true crime – many of which offer definitive accounts – Schechter writes in a highly engaging, well-paced style. A keen researcher, he includes much more than you’d expect.

On the periphery of Packer’s story are many other tales about murder and cannibalism in late 19th-century America. Some are more interesting than Packer. You also get amusing local politics, 19th-century psychology, and plenty of tabloid journalism. There’s even a counterpart to Nancy Grace in the form of Polly Pry, a gossip columnist/reform advocate who championed Packer’s cause.

As the story goes, in February 1874, against very wise advice, Packer accompanied five other men into the snow-laden San Juan Mountains, on their way to better mining prospects. This was the last time anyone but Packer saw them alive. After two months, he arrived at the Los Pinos Indian Agency alone, richer, and not much worse for the ordeal of wilderness travel in winter.

There was immediate suspicion. Packer told several conflicting stories about his missing cronies, including that they had died one at a time along the way from hunger and exposure. When he offered to show where he left them, this supposedly seasoned scout got lost. Suspicion deepened.

When the snow melted, a hiking artist, John A. Randolph, came across a cluster of decomposing remains of five men. The county coroner held an inquest and Packer was arrested on suspicion of murder. He escaped from prison, but was eventually returned for trial.

Schechter gives full accounts of the legal proceedings, separating fact from myth.

To this day, people are still divided on the issue of Packer’s guilt. Starrs, whose exhumation of the remains Schechter describes, was satisfied that he got an answer. In his forensic quarterly, Scientific Sleuthing Review, he called Packer a murdering cannibal. However, not everyone on his team agrees that evidence for murder is quite that clear.

Oh, those maddening historical crime mysteries!

I’ve read many of Schechter’s books, always in anticipation of an engaging tale, so I asked him why he’d decided to focus on Packer.

“I've actually been interested in Packer for a very long time,” he said. “As you know I have a day job as an American lit prof. When I was working on my Ph.D. many long years ago, I gave serious thought to doing my dissertation on cannibalism in 19th century American literature (Melville's Typee, Poe's Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym, Twain’s ‘Cannibalism in the Cars,’ and various works inspired by the Donner Party). But I was discouraged from doing so by my advisors, who (wisely) pointed out that the likelihood of my ever getting an academic job would be severely diminished.

“Years later, in another life, I was married to a Coloradan and spent a lot of time in her native state. I also taught for a year at the U of Colorado in Boulder, and enjoyed many meals at the ‘Alferd Packer Memorial Cafe.’ So, as I say, doing a book on the subject has been on my mind for several decades.”

Those of us who love historical crime narratives are fortunate. Schechter is a trustworthy source, offering so many intriguing nuggets to structure his tales that even readers who think they already know this story (like me) will come away enriched.