Artist and naturalist John James Audubon was a master of ornithological illustration, and also, it turns out, master of the prank.

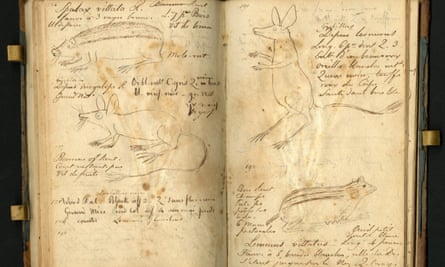

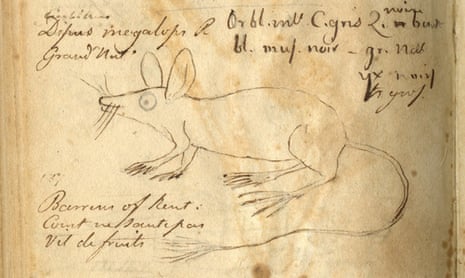

A new paper in the journal Archives of Natural History, Pranked By Audubon, sees the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History curator Neal Woodman lay out how the author of The Birds of America took time out from his superb illustrations to invent a series of “wild rats of the western states” and other creations with which to fool the naturalist Constantine Rafinesque.

Rafinesque, an excellent piece in Atlas Obscura notes, “was an extremely enthusiastic namer of species: during his career as a naturalist, he named 2,700 plant genera and 6,700 species, approximately”.

It is already known, writes Woodman, that Audubon invented 11 “fraudulent fishes” for the “too credulous ichthyologist” after Rafinesque stayed with him in Kentucky in 1818. Rafinesque went on to publish formal descriptions of the fish, but attributed them to Audubon, and the prank was discovered in the 1870s. But Woodman believes that “other organisms were involved in Audubon’s ruse as well”, including the big-eye jumping mouse, lion-tail jumping mouse and the three-striped mole rat.

“We know without doubt that Audubon provided Rafinesque with the description of one imaginary mammal, and it appears that he described nine additional ‘species’ to him. This rivals in magnitude the number of fraudulent fishes he invented,” he writes. “Audubon may have thought that Rafinesque would realise the prank, and he probably considered it unlikely that the eccentric naturalist would be capable of publishing his descriptions in scientific journals. If so, he underestimated both Rafinesque’s trusting naivety and his ingenuity in finding and creating outlets for his work.”

Rafinesque had been staying with Audubon, and Woodman points to speculation that the invention of the “fantastic animals” could have been revenge for the “violin incident” recounted in his tale The Eccentric Naturalist, which was inspired by his visit – and which bears recounting in full:

We had all retired to rest. Every person I imagined was in deep slumber save myself, when of a sudden I heard a great uproar in the naturalist’s room. I got up, reached the place in a few moments, and opened the door, when, to my astonishment, I saw my guest running about the room naked, holding the handle of my favourite violin, the body of which he had battered to pieces against the walls in attempting to kill the bats which had entered by the open window, probably attracted by the insects flying around his candle. I stood amazed, but he continued jumping and running round and round, until he was fairly exhausted, when he begged me to procure one of the animals for him, as he felt convinced they belonged to ‘a new species’. Although I was convinced of the contrary, I took up the bow of my demolished Cremona, and administering a smart tap to each of the bats as it came up, soon got specimens enough. The war ended, I again bade him good night, but could not help observing the state of the room. It was strewed with plants, which it would seem he had arranged into groups, but which were now scattered about in confusion. ‘Never mind, Mr Audubon,’ quoth the eccentric naturalist, ‘never mind, I’ll soon arrange them again. I have the bats, and that’s enough.’

Woodman writes: “Whether or not it was payback for his broken violin, Audubon’s subsequent relation of the fantastic animals was certainly in line with his sense of humour and may have been meant to test the limits of Rafinesque’s gullibility, or, possibly, his sanity. Although Audubon described Rafinesque as ‘a most agreeable and intelligent companion and hoped his sojourn [with us] might be of long duration’, he also noted with some humour Rafinesque’s arrogant condescension, and Audubon later termed Rafinesque ‘crazy’.”

There is little not to love about all this – Woodman’s dedicated sleuthing almost two centuries after the prank was perpetrated, Audubon’s mischief in dreaming up imaginary mole rats, and Rafinesque’s passion and dedication in his quest for new species. I think it’s that I like most of all – I love the description of Rafinesque that Atlas Obscura provides: the naturalist was called an “odd fish” in a letter of introduction he gave to Audubon when they met for the first time, when he was wearing a “long loose coat … stained all over with the juice of plants”, a waistcoat “with enormous pockets” and a very long beard. He sounds fantastically dedicated and utterly suited to his task.

And I am fond of a good literary prank, whether it’s the “deliberately concocted nonsense” poetry of Ern Malley, William Boyd’s artist creation Nat Tate, the “discovered” Shakespeare play Vortigern – or more recent fare, as Melville House highlights here. I’m entirely convinced that, as Rafinesque was with Audubon’s inventions, I’d be taken in by any of them.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion