War is the most decisive agent of historical change, reflected in the battalions of books regularly on parade in the shops. But once the wars have all been counted off, where can historians look for meaning? Increasingly, the tendency is to isolate a single year from which to command a view of the whole. It also goes hand-in-hand with the anniversary business.

In the last few years I’ve read social histories of 1911, 1913, 1914 and 1936, all predicated on a sense that there was “something in the air”. That may not have the emotional impact of battle lines being drawn, and it also makes the historian work a little harder for a purchase on significance – trying to link the events in X with parallel but faraway events in Y can require a leap of imaginative faith that only hindsight can verify.

Not daunted, Simon Hall has adopted just this approach in 1956: The World in Revolt, a historical panorama that seeks an interconnection in the popular mood. In choosing 1956 he is surely on to something, though the book’s separate narratives – involving Britain, the American South, the USSR, Algeria, Hungary, Suez, South Africa, Cuba – sometimes distract from the bigger picture.

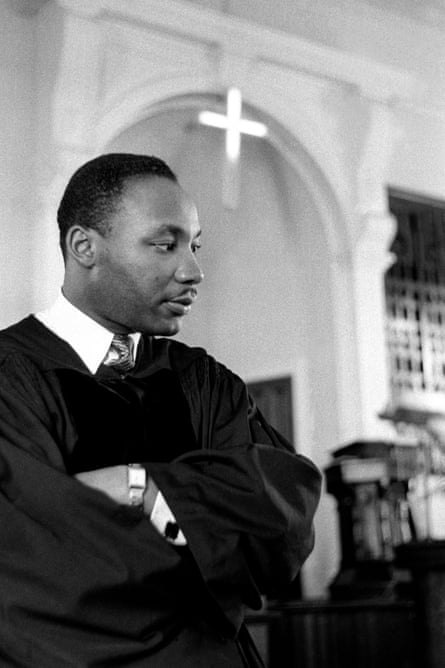

Hall’s clear prose and unsensational tone make him a civilised guide, however. He couches the timeline in four seasons, starting in winter with both the US and the Soviet Union enduring different, but equally momentous, internal convulsions. In Montgomery, Alabama, discontent with racial segregation was coming to a head. In December 1955 Rosa Parks took her famous stand – or rather seat – when she refused to vacate her place on the bus for a white passenger. Her arrest sparked a renewal of pressure from the African-American community, led by Martin Luther King, to challenge the ingrained racism of the state. A boycott of the town bus system began. In January 1956 King’s house was bombed.

Meanwhile in Moscow, at the 20th congress of the Communist party, Nikita Khrushchev delivered a speech denouncing Stalin as man and leader, who had subjected his country to “insecurity, fear and even desperation”. He was, what’s more, a “coward” who hadn’t dared to visit the front during the second world war. Though this became known as the “secret speech”, its contents were soon sending shockwaves across the eastern bloc and beyond. In the US it was considered so outlandish and reckless that the CIA director Allen Dulles suggested that Khrushchev had been drunk when he spoke. In Poland it gave the Stalinist leader a heart attack from which he never recovered; his successor described the denunciation as “like being hit over the head with a hammer”. Hall finds a resonance between events in Moscow and in Montgomery, for while segregationists were implying that integration was a “Red” conspiracy, King cannily neutralised that line by casting the civil rights movement as a heroic international cause, and a way of upholding America’s position as “leader of the free world”.

The effects of Khrushchev’s trashing of Stalin were most signally felt in Hungary, where a movement for political reform was emerging. The communist regime’s efforts to hold the line faltered as writers and artists took up the cudgels for freedom of expression. One literary gazette, Irodalmi újság, saw its circulation increase tenfold; it became such a sought after publication that at one point it was said to be changing hands for up to 30 times its cover price. Fights broke out at news stands “when supplies ran low”, which alone marks this out as a red-letter year – the last time, perhaps, that people scrapped to get their hands on a literary magazine.

Intellectual dissent filtered down to the workers; in Budapest strikes and disputes over pay began, and age-old grievances were given voice. The authorities looked on nervously. In this context cultural astonishments elsewhere might seem trivial, yet what historian could decline to acknowledge the release of “Heartbreak Hotel”? Hall neatly dovetails the repercussions of rock’n’roll with the defenders of segregation, who regarded Presley et al as making “jungle music”, which was a gateway to “interracial socialising”.

The song (“more a psychodrama than a musical performance”) also finds a prominent spotlight in 1956: The Year That Changed Britain, a chatty, informal tour d’horizon of Blighty at a turning point. Francis Beckett and Tony Russell cover some of the same ground as Hall – Stalin’s posthumous unmasking, the Suez crisis, Hungary’s tragedy – and so the story of Devon Loch at the Grand National and the debut of comedians Flanders and Swann seem somewhat parochial. Still, the book presents a useful memorial to groundbreakers in 1956 – it was the first year in recent British history, for example, “when no life was taken by the judicial system”. Less dramatically, Granada TV began broadcasting, the first Tesco opened and Jim Laker took a record 19 wickets against Australia at Old Trafford.

Some things don’t change, though, and in November the Daily Mail raised a question it has been asking more or less ever since – “What’s gone wrong with women?” It had an answer, too: “What distinguishes a woman is her lack of imaginative vitality. She will hardly ever do anything for its own sake. Her roots are so deep in sexuality that she is the natural enemy of the visionary, the idealist.” The author of this article? John Osborne. And yet one seismic cultural event of the year was Osborne’s generation-dividing play Look Back in Anger, which opened at the Royal Court to initially hostile reviews until Kenneth Tynan championed it in the Observer. “The best young play of its decade,” he declared, a public favour for which the playwright seemed to resent him ever after.

Both books climax in a double catastrophe that sealed the year’s end. The fate of the Suez canal sank any illusion of Britain’s postwar influence on the world stage. Eden’s fatal underestimation of Nasser and Macmillan’s misplaced faith in Eisenhower (“I know Ike. He will lie doggo”) conspired in a national humiliation the effects of which still reverberate today. At the time it also served to distract attention from the events unfolding in Hungary, whose revolutionary fervour had raged unchecked into the autumn. Khrushchev, having performed an ideological U-turn at the start of 1956, now made a strategic one. Fearing that instability in Hungary would infect the rest of its eastern European empire, he reversed his laissez faire policy and sent the Red Army tanks into Budapest. Resistance was suddenly and brutally crushed. Peter Fryer, a journalist holed up in the British embassy, reported it: “I saw a once lovely city battered, bludgeoned, smashed and bled into submission.”

As far as Britain was concerned, both of these books are in agreement about the legacy of 1956. It was the year the younger generation wised up to the establishment. Deference was on the way out, irreverence on the way in. In a sense, it’s the moment the 60s began.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion