On the first page of Milan Kundera’s new novel published in France last year when its author was 85 a man is walking down a Parisian street in June, just as “the morning sun was emerging from the clouds”. His name is Alain. We don’t know his age, or what he looks like, but we know that he is an intellectual because the sight of the exposed navels of the young women he passes in the street inspires him to a series of reflections, each one an attempt to “describe and define the particularity” of different “erotic orientations”.

Who else could the writer of this passage be than Milan Kundera? Two of the main tropes of his novels are present and correct, in the first page and a half: first of all, the primacy of the male gaze, fixed on the female body, “captivated” by it, and spinning an elaborate theory on the basis of what it sees there. Second, the lofty reach of that theory, which homes in on “the centre of female seductive power” as perceived not just by “a man” but “an era”: testifying to the ambition of a novelist who has made it his life’s work to forge connections between the individual consciousness and the shifting currents of history and politics.

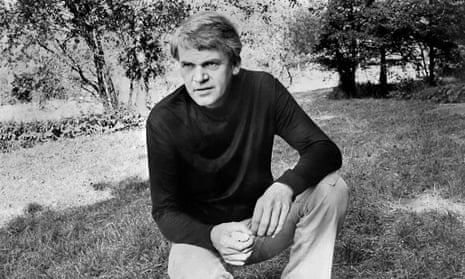

The Festival of Insignificance, then, is certainly typical Kundera, if not classic Kundera. It is an old man’s book and, while there are flickering signs of a mellow and playful wisdom, it would be surprising if there were not something autumnal about it. A glance at the back covers of Kundera’s novels in the Faber editions reveals a raft of quotes from the likes of Ian McEwan, Salman Rushdie and Carlos Fuentes, most of them more than 30 years old, reminding us that his reputation was at its zenith in the 1980s, the decade when everbody was reading The Book of Laughter and Forgetting and The Unbearable Lightness of Being.

Why did those books seem so urgent, so indispensable at the time? Was it because they coincided fleetingly with the zeitgeist, or do they embody something more robust and enduring? How will history judge them? His reputation will rest, it seems fair to say, on the three great “middle period” novels: The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, The Unbearable Lightness of Being and Immortality. Before these, we have a triptych of serio-comic novels – The Joke, Life Is Elsewhere and Farewell Waltz – vividly evoking the milieu of postwar and communist-era Czechosolovakia without staking out a claim to the formal originality that would become Kundera’s hallmark. Afterwards, we have the trio of terse, slender novellas – Slowness, Identity and Ignorance – whose very titles announce their philosophical leanings as much as their status as fictions.

The middle-period books, however, are the ones that saw Kundera finding not just his distinctive literary voice but his perfect form. They are novels of exile, written in exile. He left Czechoslovakia in 1975, having by then been dismissed from his teaching position, deprived of the right to work, and seen his novels banned from public libraries. His arrival in Paris coincided with a significant change of literary direction. The Book of Laughter and Forgetting eschews traditional linear narrative and unfolds, instead, as a nest of interconnected stories, held together in part by a handful of recurring characters but more firmly by recurring themes, words, motifs. It was as if weighing the anchor of his homeland meant that Kundera had also freed himself from the bonds of formal convention. The novel had an incredible fluidity, an enviable relaxed ease in its transitions from storytelling to essay-writing and back again.

The inseparability of form and content: this is the one of the things Kundera’s work teaches us. Writing in the novella Slowness about the most famous book of Pierre Choderlos de Laclos, Kundera observes: “The epistolary form of Les Liaisons dangereuses is not merely a technical procedure that could easily be replaced by another. The form is eloquent in itself and it tells us that, whatever the characters have undergone, they have undergone for the sake of telling about it, for transmitting, communicating, confessing, writing it. In such a world, where everything gets told, the weapon that is both most readily available and most deadly is disclosure.”

This observation, of course, comes not just from an acute literary historian, but from someone who has lived under the scrutiny of the secret police. Writing, and what it might “disclose” about its authors, is one of the most pressing themes in Kundera’s oeuvre, from The Joke onwards. In The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, Tamina, a Czech exile living in an unnamed western city, will go to any lengths to retrieve 11 lost notebooks from her native country. One of the obstacles she faces is the incomprehension of westerners: “to make people here understand anything about her life, it had to be simplified” – so she describes the notebooks to people as “political documents”, even though they are really books of memories, which she wants to retrieve not for political reasons at all, but because her memory of her early life is beginning to fade, and “she wants to give back to it its lost body. What is urging her on is not a desire for beauty. It is a desire for life.”

Through this story and its other, interconnected companions, The Book of Laughter and Forgetting beautifully illuminates the points in our lives at which identity – the very construction of our selves through memory – intersects with the political forces that are in conflict with it. It is a theme inseparable from the context in which Kundera was raised, the world of Soviet-era communism, a context which fascinated and to some extent baffled western observers in the 70s and 80s, and on which his novels seemed to open a unique window, bringing its complexities to life with unmatched irony, melancholy and intellectual rigour. No wonder that these novels seemed, on first publication, to be among the most essential literary documents of their time.

Hard on the heels of the novels themselves came a book that sought among other things to explicate them: The Art of the Novel, a collection of seven essays in which Kundera laid out his conception of the European novelistic tradition and his own place within it. The key text in his analysis was Hermann Broch’s The Sleepwalkers, a trio of novels with which few British readers were familiar at the time and which even fewer read today. (In fact you can no longer purchase a print edition in this country.) In these books Broch, too, attempted a synthesis of different modes but in Kundera’s view “the several elements (verse, narrative, aphorism, reportage, essay) remain more juxtaposed than blended into a true ‘polyphonic’ unity”. In the light of which, it’s hard not to see all of Kundera’s post-exile work as an attempt to continue the task which Broch had begun, and a triumphant one in the sense that his own blending of these elements feels genuinely seamless and organic.

Did Kundera achieve this, however, at the expense of something crucial – psychological truth to life? “My novels are not psychological,” he asserted in The Art of the Novel. “More precisely: they lie outside the aesthetic of the novel normally termed psychological.” This was a bold negative statement – a statement of what his novels aren’t – but when it came to defining what they are, he was less explicit. “All novels, of every age, are concerned with the enigma of the self … If I locate myself outside the so-called psychological novel, that does not mean that I wish to deprive my characters of an interior life. It means only that there are other enigmas, other questions that my novels pursue primarily … To apprehend the self in my novels means to grasp the essence of its existential problem. To grasp its existential code.”

This “existential code”, he went on to explain, might be expressed as a series of key words. For Tereza in The Unbearable Lightness of Being, for instance, they would be “body, soul, vertigo, weakness, idyll, Paradise”. Captivated by the philosophical brilliance of that novel (and no doubt swayed, in the case of many male readers, by its chilly eroticism), Kundera’s admirers were happy to accept its use of the existential code as a means of delineating personality; or, to put it in the terms of a more traditional literary criticism, they forgave the thinness of its characterisation. But characters tend to live longer in the memory than ideas. A few years ago, in this newspaper, John Banville wrote an interesting piece reappraising The Unbearable Lightness of Being two decades after publication. His tone was admiring but also gently sceptical. “I was struck by how little I remembered,” he wrote. “True to its title, the book had floated out of my mind like a hot-air balloon come adrift from its tethers … Of the characters I retained nothing at all, not even their names.” Conceding that the novel still retained its political relevance, he added: “Relevance, however, is nothing compared with that sense of felt life which the truly great novelists communicate.”

From his own writings, it seems that Kundera would not consider himself to be part of that tradition of “truly great” writers towards which Banville was implicitly gesturing. Many of his favourite novelists – Sterne, Diderot, Broch, Musil, Gombrowicz – really belong to that tributary of ironic, equivocal writing in which the authors are so conscious of the contradictions, pitfalls and contrivances inherent in the act of creating fictions that their books themselves become, on one level, parodies or at least self-interrogations. Kundera’s place within that particular pantheon seems secure, with one important caveat: nowhere is Banville’s sense of “felt life” more uncomfortably absent than in Kundera’s portrayal of female characters.

The feminist case against Kundera has been made often, perhaps never more eloquently than by Joan Smith in her book Misogynies, where she maintained that “hostility is the common factor in all Kundera’s writing about women”. By way of example she cited many passages, including a deeply uncomfortable one from The Book of Laughter and Forgetting in which the narrator makes a secret rendezvous with a female magazine editor who has been putting herself at personal risk by commissioning articles from him. She is so nervous about the encounter, which takes place in an anonymous flat, that she loses control of her bowels. On meeting her, however, the narrator’s main, and inexplicable, reaction is “a wild desire to rape her … I wanted to contain her entirely, with her shit and her ineffable soul”. (This is a grim passage, without doubt, but I find it more of a slander on men than anything else.)

Against Smith’s damning examples, we have to cite the number of female characters – especially in Kundera’s later fiction – who are at least as well realised as his men. Ignorance is by some way my favourite of the more recent novels, not least because its heroine, Irena, is a complex, sympathetic character whose ambivalent attitudes towards exile are explored with wit and compassion. But even here, at the very end of the book, our final image of Irena is a voyeuristic, objectifying one, as she sleeps naked with “her legs spread carelessly apart”, while her lover fixes his eyes on her crotch and “gazed a long while at that sad place”. Why does Kundera feel the need to expose his women with such thoroughness, such cruelty? And how, for that matter, could he have written a 150-page book of essays on the European novel without mentioning a single female writer apart from Agatha Christie?

I can’t help feeling that if anything will undermine Kundera’s long-term reputation, it will not be any absence of “felt life” in his novels, or the fact that his art was developed in a political context that may one day (sooner than we think) be forgotten: it will be his overwhelming androcentrism. I avoid the word “misogyny” because I don’t think that he hates women, or is consistently hostile to them, but he does seem to see the world from an exclusively male viewpoint, and this does limit what might otherwise have been his limitless achievements as a novelist and essayist. Fortunately, The Festival of Insignificance is less disfigured by this tendency than almost anything else he has written; and so, although it may not be a substantial addition to his oeuvre, it might still be a good point of re-entry for those who have been turned off, in the past, by the problematic sexual politics which send ripples of disquiet through even his finest books.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion