A crime against literature is due to be reversed, with a new edition of Anthony Trollope’s The Duke’s Children set to reinstate 65,000 words cut from the novel on its publication in 1880.

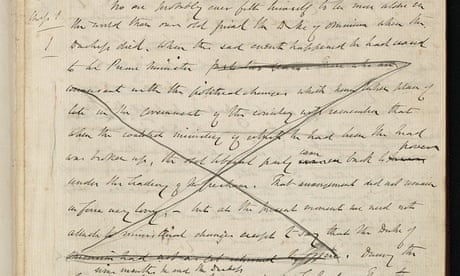

Researchers led by professor Steven Amarnick have worked for a decade on the original manuscript of Trollope’s sixth and final Palliser novel, which is held in Yale University’s Beinecke library. After painstakingly picking out the author’s scrawl from among a forest of crossings-out, they have discovered that Trollope’s excisions from the text amount to almost a quarter of the original, removing a whole volume from what was envisaged as a four-volume novel.

Now a complete, unabridged text is set to be published for the first time by the Folio Society to mark 200 years since the birth of a writer who once thundered, when asked to shorten Barchester Towers, that “no consideration should induce me to cut out a third of my work”. The Duke’s Children sees former prime minister of England and the Duke of Omnium Plantagenet Palliser widowed, and struggling to adapt to life without his wife and to support his three adult children.

“It’s quite extraordinary the different cumulative effect it has, on the richness of the text and the subtlety of the characters,” said Joe Whitlock Blundell at the Folio Society. “When I first read The Duke’s Children 30 years ago, it all seemed to be focused on the Duke’s reactions. But in the restored version, the characters of the children come through far more sympathetically.”

Amarnick writes in a commentary to the new edition that the “thousands of cuts did tremendous damage” to the work. Although Trollope did not delete any of his 80 chapters, he removed consecutive paragraphs in some places; in others, he cut sentences, phrases and words, even replacing a word with one which was slightly shorter on some occasions.

“The restored version has many more humorous touches and also has a darker edge,” writes Amarnick, adding that “the cuts diminish all his characters – often softening some of their harder edges”.

“I hadn’t realised until looking in both versions how much ironic commentary Trollope often reserved for the ends of his chapters,” said Whitlock Blundell. “He found that one of the easiest places to make cuts because it didn’t interrupt the flow, but it means lots of ironic commentary was missing – and he’s all about the irony.”

Whitlock Blundell speculates that Trollope “would have been incandescent” over being asked to make the cuts; the precise reason for them is “lost to posterity”, says the Folio Society, but “is likely to have been a demand from his publishers on the grounds of economy”.

“There is no concrete evidence for who exactly forced him to make the cuts, though it seems probable that it was Charles Dickens Jr who requested a shorter book for serial publication,” said Whitlock Blundell. “As for his reluctance, there can be no doubt about it. He was very sensitive to any requests to cut his work, and wrote in his autobiography, ‘I am at a loss to know how such a task could be performed. I could burn the MS, no doubt, and write another book on the same story; but how two words out of every six are to be withdrawn from a written novel, I cannot conceive’.”

Trollope expert Dr Margaret Markwick, of Exeter University, believes Trollope would have been delighted to see his original work restored. “The major issue is clearly the speculation on what Trollope thought of being asked to cut his novel by a quarter, when he had spoken so unequivocally about the impossibility of cutting Barchester Towers,” she said. “And yet, here he is, doing an almost seamless job on The Duke’s Children.”

Markwick said that at the time Trollope had been “stung” by the “very poor reviews” of his preceding Palliser novel, The Prime Minister, was in “poor health” and in a “much different frame of mind when he was asked this time round to reduce his text”.

“Ever-sensitive to the criticisms of The Prime Minister, and ever the pragmatist, he set about cutting his text with considerable thought and skill, working on it for two months in 1878. That he took such care over the cuts makes me think he did it with good grace. That it should now come out in its original form I think would delight him,” she said.

The unabridged version of The Duke’s Children is being published this month in a limited edition, priced at £195, by the Folio Society, with an introduction by the novelist Joanna Trollope, a fifth generation niece to the author. The publisher hopes eventually that a mass-market version of the restored text will be released, which it expects will become the standard version of the novel.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion