Usually, when a writer as widely read as Ann Rule dies, the internet gets papered over with heartfelt tributes. That didn’t happen for her – there are obituaries everywhere, but few eulogies – and I’ve been ruminating on why. My own adolescent bookshelf held battered paperback copies of some of her books – I must have read The Stranger Beside Me and Small Sacrifices at least 10 times each – and I was hardly alone: she was the kind of writer whose sales counted in the tens of millions.

In other words: she was doing something that inspired devotion. It just wasn’t the kind that people have been willing to cop to, now or ever. Even I wouldn’t call myself a “fan”, exactly.

Rule never claimed literary status. She never seemed to mind, either, that she wasn’t accorded it. She told one interviewer that as far as she was concerned, “financial success is critical acceptance”, and she certainly did make money. In fact, she made enough that in April news broke that her sons were demanding more of it from her, as she “cowered in her wheelchair”. But other writers who had financial success manage to elicit in their readers an affection for the author that Rule never did. Partly, obviously, it had to do with the genre she worked in.

True crime lives in an uneasy place in the American psyche. It is, as Joyce Carol Oates once primly put it in the New York Review of Books, a genre “enormously popular with readers”. Yet it still feels a little embarrassing to talk about loving to read about crimes that actually happened. Serial and The Jinx put a slightly more highbrow gloss on the subject. It is now not totally gauche to confess, at a party, that you spend your late nights perusing the Wikipedia list of serial killers. But we still look askance at anyone who stares too long and too openly at the details of a murder. The interest is still classified as a prurient one. And Rule went back to the dark well again and again. When she died she had over 30 books to her name, each claiming to be the work of a deep investigation into evil.

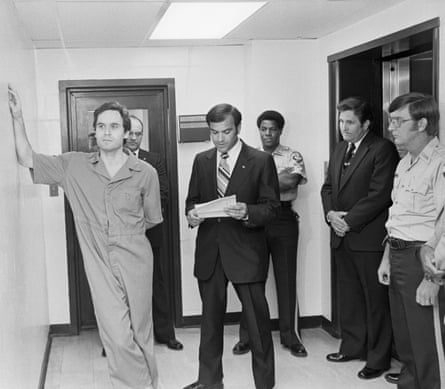

Rule operated on a pretty simple moral philosophy. The “downside” of her line of work, she said, was “meeting evil people”, and she had no trouble marking a bright line distinguishing them from the good ones. Funnily enough, Rule’s career was staked on the idea that she once hadn’t been able to see the evil sitting right beside her. In May of 1975, after writing for a pulp magazine called True Detective for years, she signed a book contract with WW Norton on an advance of $10,000. It was to be the tale of a number of linked but unsolved murders of young women in the Pacific north-west. By the fall, she’d learned the name of the prime suspect, Ted Bundy. And she’d realized that she knew him; had met him while working a crisis line about four years earlier. And he was willing to talk directly to her.

So the resultant book, The Stranger Beside Me, became more than an account of the Bundy case. The murders were lurid enough in themselves – Bundy liked to kill with blunt instruments, and he also liked to boast of the way he chose to dispose of bodies – but Rule piled on her own feelings of horror to the point where reality reads just like a supermarket thriller. Example: at one point in the book Rule describes visiting Bundy in a Utah prison, where he pleads for her help with, among other things, getting a book contract. She walks out thinking “No, no … he couldn’t have done it.” But that night, she dreams of finding and rescuing a baby who turned out to be a demon, which “sunk its teeth into my hand and bit me”.

“I did not have to be a Freudian scholar,” Rule remarks then, “to understand my dream.” No, indeed the symbolism in a Rule book rarely required much by way of interpretation. In Rule books men are often described as “strikingly handsome”; killers have “dark moods”; people “disappear into the night”. The cliches are what kept the serious critics away from her, no doubt, but they were often wielded deftly, with a really rather admirable seasoned-hack’s sense for what her public expected. Literary standards prefer writers who upend a reader’s expectations, but there is a distinct skill in knowing just how to keep people hooked to your mass market paperback. And Rule certainly had it.

More than other kinds of writers, she had her misgivings about her life’s work. She would sometimes complain that she worried about making a living off other people’s tragedies. Even fans of her work troubled her slightly: in a 2008 preface to a reissue of the book, she expressed dismay at all the mail she got over the years from young women who told her they loved Bundy from afar. She said she blamed herself for describing Ted as so attractive, that she’d wanted to “warn readers that evil sometimes comes in handsome packages”. She called herself “naive” about her ability to get that message across.

A Denver newspaper once asked Rule what she thought of Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood. “Capote became too entranced with Perry Smith and Dick Hickok [the killers],” she replied. “He felt more of Perry Smith’s pain than he did of the victims, the Clutter family.” Rule preferred, she said, to focus on victims in her own work. I think this was a bit of dissembling, that surely every true crime writer knows that the killer attracts more fascination and even empathetic imagination than the prey. It’s a phenomenon that is plain as the light of day. Just compare how much you know about The Jinx’s Robert Durst to what you know of the woman with whose death he stands charged, Susan Berman.

Rule liked to talk about victims, I think, because she also liked to think of herself as a defender of women, even though some of the killers she covered were female. And it does seem like so much of her appeal was bound up in some very deep, almost primal understanding of how gendered a lot of the violence in the world actually was. She came by that knowledge honestly; before she’d begun writing in the 1960s, she’d worked in a vice squad. “I was a 20-year-old virgin in the morals unit, taking rape statements, working for the bunco squad, and decoying for gypsies and con men. I worked with runaway girls in the days when we actually tried to find them. And I worked in child neglect,” she told the Denver Post in 1991. “Never murder. Women weren’t welcome in the homicide unit.”

Rule certainly proved, over the course of her career, that she should have been let in. Not because she truly solved any cases, but because if there was one thing she understood well it was obsession. Not just with the details of a murder case either, though there was that. She understood that she lived in a society both terrified of and obsessed with killing. And when I think about what led me to read and reread those horrifying stories over and over again as a teenager, I realise that it was actually pretty simple: I wanted to read about crime because I wanted to shine a light on the dangers that adults said lurked out there.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion