The internet is not the answer. But who said it was? And hang on, what was the question again? The internet is a good answer to a question like “What do we call the global network of computer networks?”, but a bad response to “What would you like to drink?” The internet is a very good answer, in the sense of “approach or solution”, to the problem of sending a written message very quickly to someone on the other side of the world, but a poor one to the problem of constructing a better society.

Or is it? For Andrew Keen, noted gadfly of the tech world, is in this sardonic treatise concentrating his rhetorical fire on a class of people who really do think that the internet is the answer to all our current problems: not only in, say, getting a taxi or a sex partner, but also in education and politics. These are the techno-utopians of Silicon Valley, the wealthy or wannabe-wealthy libertarians with a fetish for “disruption”. It is to their brand of what another critic, Evgeny Morozov, calls “solutionism” that Keen is eager to retort in the negative.

Expressions of such a worldview are becoming more common outside the startup bubble, too. In the last episode of the BBC Radio 4 series Can Democracy Work?, for example, the Ukip politician Douglas Carswell was celebrating how the internet “democratises” everything, including the fusty old political process. And yet, as one of the most forceful and angry threads of Keen’s book demonstrates, the idea of the internet as inherently “democratic” is just a holdover from its hippy early days.

The internet now, after all, is dominated by giant monopolists (Google et al) for whom we, in our searching and Liking, act as unpaid serfs. We live voluntarily in an “electronic panopticon”, all the more so if we buy into the new wave of bio-sensing “wearables”. And the big internet companies taken together, Keen argues, are a net destroyer of jobs – jobs in independent bookshops, say, or taxi firms.

What happened? Keen reminds us that, as is often forgotten, the internet was privatised. In the early 1990s, the US government “handed over the running of the internet backbone to commercial internet service providers”. One super-wealthy tech investor called this moment, with a degree of smugness that it is tricky to gauge, “the largest creation of legal wealth in the history of the planet”. Keen himself offers a trenchant geopolitical analogy: “Just as the end of the cold war led to the scramble by Russian financial oligarchs to buy up state-owned assets, so the privatisation of the internet at the end of the cold war triggered the rush by a new class of technological oligarchs in the United States to acquire prime online real estate.”

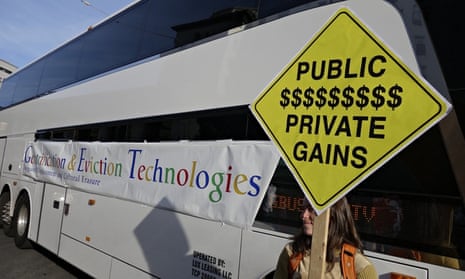

All this acquisitive disruption has, as Keen points out, concrete consequences. The lure of high daily Airbnb rates is causing landlords to drive up long-term rents in San Francisco and elsewhere, which is not good news for those who don’t take the “Google bus” to work. Twitter offers its employees free food, which “has destroyed the business of local restaurants and cafes”. The music industry, meanwhile, has been savagely injured by what Keen calls the “networked kleptocracy” inaugurated by Napster et al.

Keen is especially angry about what has happened to music, since, as he relates, he grew up at the end of the golden age of Soho record shops, and founded his own early music startup, AudioCafé. “Back then,” he confesses, disarmingly, “it really did seem as if the internet was the answer. The web ‘changed everything’ about the music industry, I promised my investors.” As it turned out, it did, but not in a good way.

Less convincing is Keen’s nostalgic tour of Rochester, NY, headquarters of the photographic company Kodak, which was driven into administration. Keen describes it as a ghost town, where thousands of former Kodak employees have been screwed on their pensions. It is very sad. But is it really, as Keen implies, the fault of photo-sharing app Instagram, or even the internet in general? After all, as he concedes, Kodak was mismanaged for years, even after having invented the very first digital camera.

Even if it makes sense to consider “the internet” as a single entity, which is doubtful, it’s not clear that it always deserves the blame for the cultural and industrial changes that Keen laments. Another of his examples is WhatsApp, the phone-messaging service, which had only 13 full-time employees when Facebook bought it for $1bn. “Meanwhile, in Rochester,” Keen continues, “Kodak was closing 13 factories and 130 photo labs and laying off 47,000 workers.” That is a striking juxtaposition of figures, and also a non sequitur. WhatsApp had nothing to do with the photo business. And it gained traction because of cynical price-gouging by the mobile operators on the cost of SMS text messaging: unlimited international texting for a dollar a year just made WhatsApp a better option.

Keen is on firmer critical ground when arguing against the trend for anonymous-messaging apps, which have even caused famous investors such as Marc Andreessen to balk, since they enable a climate of unaccountable hostility and bullying. In general, Keen accurately observes, on the internet “there are too many abrasive young men with personality defects and not enough accountable experts”. (It is notable, indeed, that cyberhustlers are always denouncing “gatekeepers” while secretly hoping to become the new gatekeepers themselves.)

What, then, is the answer, if it isn’t the internet? For Keen it turns out to be something rather old-fashioned: democracy, and an arguably rather idealised version of it at that. “The answer,” he at last reveals, “is an accountable, strong government able to stand up to the ‘alien forces’ of Silicon Valley big data companies.” The internet companies are rebuilding the world “without our permission”, has been his refrain throughout. But governments can do it “with our permission”. So we should cheer on the EU and other political institutions who seek to regulate and rein back the excesses of the tech “robber barons”. One can very well agree with this, however, without imagining that it will amount to much more than fiddling around the edges.

In the end, Keen obviously doesn’t think everything about the internet is horrible: he is careful to point out early on, indeed, how much of a boon it can be. The intellectual vigour and polemical momentum of his book, though, are often undermined when he veers off into riffs so splenetic they might have been penned by a doddering misanthrope who has never touched a smartphone. He thinks selfies are just “embarrassing” (depends on the selfie, if you ask me), and even finds it in him to write: “The real myth is that we are communicating at all. The truth, of course, is that we are mostly just talking to ourselves on these supposedly ‘social’ networks.” Really? If that’s true, I guess I ought to unfollow @ajkeen.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion