Pat Barker returns from being photographed having encountered, en route, a dead pigeon. Wouldn’t it have been better, she jokes, if Martin Amis had been there instead of her? I see what she means: Amis’s writing, and certainly the persona that has been created for him, more obviously lend themselves to such a macabre prop. But, alas, “there the poor photographer was, stuck with me. I think I’m fairly edgy, but not dead pigeon sort of edgy”. It’s not true, of course. Not only do stricken pigeons actually feature in her new novel, Noonday – their wings ablaze during the so-called second great fire of London at the height of the blitz – but her work returns over and again to notably painful and complex subjects. Ranging widely, her books require her to confront and convey violence both personal and military, the morality of war, class and sexual conflict and the nature of psychopathy. In her early novels she focused on the day-to-day lives of working-class women in the north-east of England, making a debut so striking with Union Street (1982) that she was included on Granta’s inaugural selection of the Best of Young British Novelists (she was photographed alongside, among other luminaries, one M Amis). In 1991 she began her epic Regeneration trilogy, which concluded in 1995 with the Booker prizewinning The Ghost Road; and, in Border Crossing and Double Vision, she explored both the internal life of and society’s response to a child who kills.

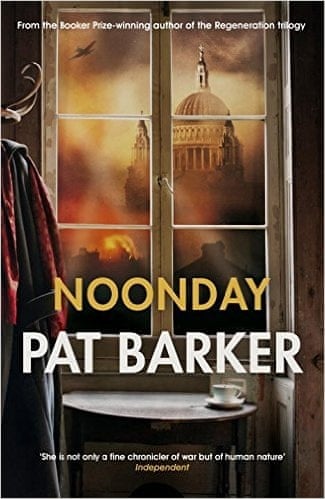

It has often been remarked that Barker is a novelist who regularly reinvents herself, and now she is once again going into brand-new territory. The writer responsible for one of recent decades’ most subtle and powerful fictional depictions of the first world war is setting her sights on the second world war. Noonday is the conclusion of the trilogy that began in 2007 with Life Class and continued in 2012 with Toby’s Room; but while in the first two instalments, Barker’s protagonists, artists Paul Tarrant, Kit Neville and Elinor Brooke, found their youthful vigour and ambition hijacked by events in France and Belgium, now they are middle-aged, and the battle they face is far closer to home.

Why did she do it? If she wanted to write a trilogy, why end it by fast-forwarding 23 years? Well, she answers, she wanted to show the way in which men of Tarrant and Neville’s generation found the second world war far more shocking than those who had never experienced combat: “I just thought what a terrible thing it must have been for men who had fought in the first world war to see a toddler wearing a gas mask, because gas was so much a part of their experience ... And to have gas cots, as there were for babies; I think what that generation felt very often was a bewilderment, and a sense of complete failure, because they had won the war, ostensibly they’d done everything anyone could possibly do, and yet here they were facing in many ways an even worse menace.”

A key element in the two previous novels was their female lead Elinor’s relationship with her brother, Toby, killed at the front in ambiguous circumstances. It animated Elinor’s anti-war stance, and her belief that artists, and indeed women, who are not allowed to participate in the decision-making should turn their faces away from combat. In the opening pages of Noonday, she stands in the hallway of her familial home, contemplating Toby’s portrait, reflecting on “how guilty they all felt, then and now. Especially now, when another generation of young men was dying. We dropped the catch, she thought. Our generation.”

But, as Barker explains, Elinor’s position becomes even more complicated: “Of course the home front is in fact the combat zone. Paul says, ‘People didn’t take their wives to the trenches’, and Elinor says, ‘No, but the trenches didn’t run through the family living room’.” As she drives her ambulance around the blitzed streets, “she accepts that, in some sense, this is her war, her city is being attacked”.

Noonday revisits many of Barker’s abiding preoccupations and fictional hallmarks: echoing Regeneration’s Billy Prior and Border Crossing’s Danny Williams, there is a lost boy, Kenny, who is both abandoned and let down by many of the adults around him, but who is also manipulative, crafty, occasionally unscrupulous (rescued by Paul, he later insinuates inappropriate behaviour on the adult’s behalf in order to ensure his return to his mother: “I rather admire it,” says Barker. “A real survivor’s instinct.”). There is also the interrogation of art’s usefulness, or otherwise, when the nation is in extremis, and concomitant questions of propaganda and censorship. And there is the intensively researched but also keenly felt sense of place.

This time, that place was London. “It was very strange,” says Barker, who was born and bred on Teesside and, apart from three years at the London School of Economics in the 1960s, has never strayed far from it. “When I finished this book, I realised that I love London. But when I come out of King’s Cross station, it’s either the tube or the taxi rank, both are utterly horrible, and I experience London as a great big traffic jam. I just think, I want out of here as fast as I possibly can. And yet, unmistakably on the page, there is a love of London. It surprised me. It took me a long time to realise it, now it’s the third book.”

It is, admittedly, the capital city of the past – indeed, she laughs, “perhaps I like London in ruins” – and one significantly altered by the very subject she is writing about; walking the streets, she says, was inevitably frustrating, because the heavier the bombardment, “the less there is there when you go back”. But that fed into another perspective, the idea of London as a haunted place. Much of the time, Barker is a determinedly unshowy writer – “I just couldn’t write in an adorned way,” she insists, “to me that would feel insincere” – but in all her books, her restrained prose will suddenly be punctured by an arresting, and often uncanny, image. In Noonday comes the idea of “London’s dead gurgling up through the drains”, the juxtaposition of the desperate, threatened citizens of the second world war with those of a far older era. As Barker explains it: “There’s this feeling that if it’s total blackout, and you’re in a city where you don’t know the people you’re walking past anyway, how would you know if you encountered a ghost? You couldn’t possibly know. There’s nothing that would tell you.”

I ask her whether this is specifically a way of connecting conflicts past and present, of making a continuum of this type of experience. Does she feel, when she writes about the soldiers of the first or second world war, that she is somehow writing about other combatants, and other times?

“I think so. And I think it became easier to do it in this book. You have to write about the particular war, but you’re always in a sense writing about all wars, however many differences there are. Paul thinks, these men could be back home from Dunkirk, or they could be stragglers from Boudicca’s army. From the point of view of the common soldier, one cock-up is the same as another.”

Ghosts and war: not a bad prism through which to approach Barker’s work, nor to understand its strangely hypnotic power. She has told, in the past, the story of her grandfather’s bayonet wound; how habitually seeing it as he washed in the kitchen sink prior to nights out at the British Legion lodged in her imagination, perhaps particularly because something so redolent of damage and pain had been absorbed into everyday domestic life. But that man was her grandmother’s second husband; the first, who died at 49 and whom she never knew, also had a story to tell.

It comes out as we talk about Noonday’s Bertha Mason, a medium to whom Paul finds himself reluctantly drawn, and who is partly based on Helen Duncan, who was convicted and imprisoned as a witch in 1944 because she revealed that a British ship had been sunk with all hands, even though no official announcement had been made (later, the information was found to have been leaked, and the sailor’s hatband that Duncan produced as evidence to be a fake). Mason is a compelling character, a grotesque with a terrible past who, says Barker, arrived rather suddenly: “there she was, rabbiting on, you couldn’t shut her up. Oh dear! She was very startling.” Such a takeover, she explains, was unprecedented, and the kind of thing she normally associates with “people who are more, what shall I say to be kind, wiffly-waffly about writing novels”. But this time, it was undeniable: “She was infuriating, because – it’s never happened to me before – she thought it was her book. She wasn’t an entirely benevolent presence. Not in the least, in fact.”

Barker’s grandfather does not sound much like Mason. He was, she says, a very bright man with little outlet for his intelligence; in poor health for much of his life, he had left school early and was “more or less permanently unemployed”. But he did have his life as a medium – including “a very boring spirit guide. He was an Indian chief. A lot of them are Indian chiefs.” He also did faith healing, which involved him taking on the symptoms of the person he was attempting to cure. “It was very much a working-class religion, but it was also very much something that women did. Partly because of the total passivity of it: you’re just going into a trance and the dead speak through you, so if the medium was ignorant and educated and illiterate, it didn’t really matter.”

In her work and in conversation, Barker is brilliantly astute and articulate on how class issues are part of the warp and weft of British society, and how they have had an impact on historical events. After all, she explains, “the greatest mediums would have famous novelists, cabinet ministers, all kinds of people coming to them for consultations, listening to not very well-educated women talk – well, in no other circumstances did that happen. It was actually a kind of empowerment.”

As, of course, war itself could be. Barker recalls her mother, Moyra, who was a Wren stationed in Dunfermline, talking enthusiastically about the war: “She absolutely adored it from beginning to end – well, she adored it until I arrived. It was the best time of her life; it was dynamic, she joined the forces, she left home. She was with large numbers of women, many of them from different walks of society, so it was a kind of education for her. She believed absolutely in what we were fighting for, as the vast majority of people did, of course. She just had a thoroughly good time.”

But there is a lot behind that “until I arrived”. Amid the dancing with Polish officers, and encountering a lesbian for the first time, Barker’s mother became pregnant, giving birth to her daughter in 1943. Barker never knew who her father was and, she says, honestly doesn’t believe that her mother “had any real memory of who he was, or anything about him”. She and her mother lived with her mother’s parents in Thornaby-on-Tees, but when Moyra married, Barker, then seven, remained with her grandparents. Eventually, Moyra had five children: two stepchildren, two children with her husband, and Barker. But, says the novelist, “sometimes she counted her natural children and said three, sometimes she said two. And that was strange.”

However, she says, “It’s awfully easy to talk about it in a way that implies self-pity, but I don’t feel like that. I think it’s an interesting situation, to have half your genetic inheritance completely missing.” The only thing that bothers her, she maintains, is the “inconvenience” of not knowing enough about her medical history. “Otherwise I think it’s a sense of freedom, which may be illusory, but I think it increases your ability to invent yourself.”

When her mother died, about 20 years ago, Barker realised that any chance of that missing information coming to light had gone forever. “I expected to feel upset about that, and I didn’t, I felt relieved. I thought, right, that’s over. That door is closed forever now, and I can get on and be me.” Her mother, she thinks, had felt a great degree of shame about her first child’s birth, and had never managed to rid herself of it because, later in life, she became a Jehovah’s Witness, “so it went on being a very sinful act, whereas for most people, of course, it was nothing. There was no moving into what the 60s, 70s and 80s did for women.”

Did Barker herself ever carry any of that shame? “To a degree, yes, in the 50s I did, but unlike my mother, I sort of left it behind,” she replies. “I suppose it did shape my life negatively, but not in a way that stopped me being happily married, or having a career, or bringing up my own children. So if you regard those as signs of normality, it didn’t have that much negative impact. And also, of course, if your parents don’t fuck you up, what are you going to write about?”

She started writing stories as a child; success in the 11-plus meant that her educational opportunities were not curtailed as those of previous generations had been. After school, she journeyed south to read international history at the LSE, and then returned north to Durham, where she gained a diploma in education, and thereafter became a teacher of history and politics.

She wasn’t published until she was nearly 40; by then she had had children and married (in that order: she and her husband, David, a zoologist 20 years her senior, had had to wait to marry until 1978, when he had become divorced; their children John and Anna, also a writer and now her first reader, were born in 1970 and 1974 respectively). Her creative breakthrough – she had written novels and discarded them – came on an Arvon course taught by Angela Carter, although publication was still some way off. But what Carter did for her, Barker remembers, “was to say that what I was doing about working-class women was interesting and that I should go on doing it. So she did not so much teach as give me faith in my own voice. The best teaching is to recognise the voice and encourage it, and gently discourage attempts to be somebody else. And Angela was a very, very good teacher.”

On the course, Barker wrote a short story about two women which was set during a miners’ strike; it was to become part of the ending of Union Street, which opened with the rape of an 11-year-old girl and followed the lives of several women over the course of a few months. The book was published by Carmen Callil at Virago Press, which had been founded nearly a decade previously, and was followed by two others, Blow Your House Down (1984) and The Century’s Daughter (1986; reprinted in 1996 as Liza’s England). It is tempting to see the books not only as a trilogy-of-sorts, but also as part of a discrete period in Barker’s career, at the end of which she moved to the entirely different territory of the war, and from describing women’s lives to men’s.

Barker does not see that creative trajectory in quite such neat terms. For a start, the novels have much more in common with one another than you might imagine: “I think if you look at Mason in Noonday, she could be on Union Street,” she says, and she’s absolutely right. And not only was there a book in between her early work and the Regeneration trilogy – 1989’s The Man Who Wasn’t There, which has as its protagonist a 12-year-old boy who imagines for his absent father a heroic wartime career – but there was a degree of necessity at play. “It’s much more blended than people think it is,” she explains. “I do think there was this kind of artificial thing that happened at the beginning because I was published by Virago and if you write for Virago you have to foreground women’s experiences. And I think after Union Street and Blow Your House Down, I would have moved on to representing both sexes much earlier and much more easily, in a sense. So I think that was a slightly distorting effect.” Was she aware of it at the time? “I was getting very restless towards the end.”

She concedes that she went “to the other extreme, and wrote about men in an all-male institution”. But in Regeneration, The Eye in the Door and The Ghost Road, she created a body of work that treated war in an unfamiliar way, mingling the real historical figures of Siegfried Sassoon, Wilfred Owen and the psychiatrist William Rivers with the extraordinary figure of Prior, a bisexual working-class soldier who, when we first meet him, is suffering from shell shock and, as a consequence, elective muteness. She is drawn, she says, to “the almost sociopathic character, who is never quite sociopathic – Danny Williams is the closest to being absolutely abnormal. But Prior has a code of morals; it’s not the same as anybody else’s, but he’s got one.” Prior – in common with the medium Mason and other of her characters – also reflects her interest in dissociated states; fugue-like mental episodes often caused by deeply repressed trauma, but also, in the case of writing, for example, capable of provoking creativity.

The trilogy gave Barker an enormous profile and a major prize; the Booker, she says, “changes the landscape totally, in ways which are marvellous, but also seem quite threatening at times. It’s a sort of ‘follow that’ feeling, which is very strange, a very exposed feeling. It takes time to get used to it.” After “following that” with three very different books, she embarked on another trilogy, this time bringing in a prominent female character and creating a memorable, and indeed fleetingly incestuous, brother-sister relationship. Once again, a real figure is mixed among her fictional creations: her characters start life as students at the Slade School of Art, where they are taught by Henry Tonks, artist and surgeon, who later makes drawings of servicemen with severe facial injuries before and after their treatment; Kit Neville is one of them. In Noonday, Kenneth Clark makes an (albeit small) appearance.

There were five years between the publication of Life Class and Toby’s Room, primarily because Barker spent two years caring for her husband before his death in 2009. It has been, she says, with characteristic understatedness, “a very much bombarded trilogy”. Given the relationship between Toby and Elinor (the title Toby’s Room, as Hermione Lee pointed out when she reviewed it, echoes Virginia Woolf’s Jacob’s Room, also a memorial to a dead brother), the trilogy would always have been suffused with grief; but Barker agrees that her own bereavement gave it an extra dimension.

“You use the experiences you have. It wasn’t the first grief in my life; it was the deepest so far – let’s hope nothing else awaits,” she says. “I find the whole stages of grief thing quite interesting, because nobody talks about stages of falling in love, for example, or things like that, and I think it’s a way of people distancing themselves, taming the experience, which is actually an experience that can’t be tamed. It’s one of these things that strips the flesh off your bones, and that is the truth about it. There aren’t any neat stages, and there is nothing that can be identified as recovery, either, although obviously you learn to live with it, and through it, and differently because of it. But certainly, as soon as people talk about recovery, I just think, ‘Ah, it hasn’t happened to you yet.’”

When I ask her whether she is sure that the trilogy is really over (some characters’ stories are finished, others not so) she gives an agonised cry and then laughs. “Oh, don’t say that!” She thinks that her first foray into the second world war will probably also be her last. But would she write another trilogy? She shakes her head. “It’s a bit like dog ownership. You know you’re too old to start another. A part of you thinks, ‘well it’s sad in one way’, but no, it isn’t really.” Yes, I remark, but then people do continue to get dogs, don’t they, even when they’re not sure they should; they can’t help themselves. “Well, they do,” she replies, “I mean, you can rehome them, but I don’t know what you would do with two books of a trilogy. Nobody could actually write the third for you.”

No, she says, it’ll be standalone novels from now on, and maybe even quite short ones: “I think I deserve a novella after all that … I’ve put the hours in.” For her next book, she’s going to write about the slave girl whom Achilles and Agamemnon argue about in the first section of The Iliad, which she describes as “an extremely realistic account of warfare and what happens to men in warfare”. “I’ve got her voice,” she says. “I want to try to tell as much of the story as I can in her voice, through her eyes.” It will be set in the period, rather than transposed to another and is, she agrees, “a huge departure”. Does it feel at all frightening? “Not frightening, no. It’s so different from what I’ve been doing before … ”

I note that she has never written about a contemporary conflict, and she answers that she thinks it would be too difficult to acquire both the in-depth knowledge and the necessary distance to write fiction. “I was once invited by William Deedes [the editor of the Daily Telegraph] to go to Somalia and write about that, along with a lot of other writers,” she recalls. She didn’t go. “If you think about what we could actually have written about it, we’d have been writing about a lot of novelists going to Somalia. That would be all we could actually understand.”

She is always on the alert for the kind of highly polished “fake-work” that it can be all too easy to write; material that looks “respectable” on the screen, but is quite dead. After all, she says, “there are uncomfortable resemblances between novelists and mediums. One of them, of course, is that sometimes it’s genuine and sometimes it’s fake. And the trouble is that once you’ve got the techniques, you can produce a fantastic fake.”

For all its ambiguities, and for its lack of didacticism, her work has a clear moral imperative. Does she think, therefore, that it’s important? “I think you need the delusion at least that it’s important,” she replies. “Why else would you do it? Sitting in a room, dressed like Orphan Annie, tearing your hair out, it’s not instrinsically appealing. So you do need the delusion that it’s important. But I certainly don’t think novels change the world – nor even tiny little fragments of the world. On the other hand, it is important to tell the truth. And, oddly enough, I do believe the truth is instantly recognisable.”

An extract from Pat Barker’s Noonday

Closing the door on the merciless moonlight, he went round the drawing room checking the blackout curtains were in position and switching on the lamps. Then he turned to look at Kenny, who was staring blankly around the strange room. Now what? What on earth am I supposed to do with him? The sirens were sounding for the second time that night. They ought, really, to go to one of the public shelters, but he couldn’t face going out again and he didn’t think Kenny could either.

“We’ll sleep in the hall,” he said. “We’ll be safe enough there.” A few weeks ago, when the nuisance raids started, he and Elinor had dragged a double mattress downstairs. They’d lined the walls with other mattresses and cushions from the sofa and he’d made sure all the windows were taped against blast. Of course, none of this would protect them from a direct hit, but then neither would most of the shelters. “Why don’t you settle yourself down? I’ll see if I can find us something to eat.” And drink.

In the kitchen, he opened and shut cupboards, found half a loaf of bread (stale, but it would have to do), a couple of wizened apples, a slab of Cheddar just beginning to sweat and a bottle of orange juice. Then he poured himself a large whisky and carried the tray into the hall.

Kenny had tipped the toy soldiers out of the bag and was arranging them on a strip of wooden floor between the mattress and the drawing-room door. He looked up, white-faced, on the verge of tears again but blinking them back hard. “Why can’t we go tonight?”

“Because it’ll be absolute chaos and we’ll only get in the way.”

“We could help.”

“I don’t think so. Anyway, I doubt they’d let us anywhere near.”

Thumps and bangs in the distance. “Look, I’ll take you first thing in the morning, soon as it’s light. Sorry, Kenny, best I can do.” A nearer thud shook the door. “Come on, have something to eat, it’ll make you feel better.”

Kenny was tearing off a chunk of bread with his teeth. “We could play.” “Play?” Kenny nodded towards the soldiers. Well, why not? It would take his mind off it. So they munched apples, cheese and bread, drank whisky and orange juice, moved cohorts of little figures here and there until, eventually, even Paul became absorbed in the game. The background clumps and thuds blended in really rather well. Kenny was the officer, of course. Paul was a not-very-bright NCO. Now and then, an explosion rattled the window frames – and, yes, he was afraid. Nothing like the fear he’d experienced in the trenches; though, in one way, it was worse: he was experiencing this fear in the safety of his own home, and that meant nowhere was safe. More than once, he was tempted to go out and try to see what was happening, but he didn’t want to interrupt the game – it was so obviously helping take Kenny’s mind off the bombs – and so they played on, metal armies advancing across strips of parquet floor, rather more quickly than they’d done in life; Passchendaele and the Somme played out on the floor of a house in Bloomsbury. “Yes, sir!” Drifting clouds of smoke obscured the salient. “Right you are, sir!” A shell landing in a flooded crater sent sheets of muddy water thirty feet into the air. “Going out to take a look, now, sir!”

Kenny would have to sleep soon, his eyes were rolling back in his head, but my God he fought it. Finished his orange juice, asked for more … This time, Paul tipped a little whisky into the glass and, although Kenny wrinkled his nose at the funny taste, he drank it all down and shortly afterwards curled up on the mattress and went to sleep.

Paul began to clear the soldiers away, then stopped, selected two and looked at them, lying side by side on the palm of his hand. Somehow, last time he’d seen them, he hadn’t quite realised what it meant. My God, he thought. We’ve become toys. He wanted to share the moment, the shock of it, but there was nobody who’d understand.

He slipped the little figures into his pocket, lay down beside Kenny and went to sleep.

In the middle of the night, Kenny woke up and shook Paul’s arm. “You hear that?”

Paul struggled to wake up; he must’ve gone very deep, he could hardly force his eyes open. They lay listening to the thuds until one blast louder than the rest made Kenny cry out. He was too big to ask for reassurance, too young not to need it. Paul touched his arm. “Don’t worry, it’s all right.”

“Is it true, you don’t hear the one that hits you?”

“Yes.” Said very firmly indeed, though he’d certainly heard the shell that had hit him; he’d heard it shrieking all the way down. Still did.

Kenny was sitting up, wide-eyed, quivering like a whippet at the start of a race. “Can we go now?”

“Soon as it’s light.”

“What time is it?”

“Three thirty. Come on, go back to sleep.”

“I can’t sleep.”

Nor could Paul.

“You know, we mightn’t be able to get there. There won’t be any buses or taxis. And I’m not driving through that.”

“We can walk.”

No point arguing. And anyway he didn’t know. No more than Kenny could he guess what they would have to face. “Well, I’m going back to sleep,” he said. “And if you’ve got any sense at all you’ll do the same.”

He turned on his side and lay in darkness, waiting for the change in Kenny’s breathing. Only when he was sure Kenny was asleep did he let his own eyes close.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion