Less than two decades ago, Japan positioned itself in the vanguard of the global fight against climate change when it helped broker the Kyoto protocol.

Now, though, it is Fukushima, not Kyoto, that has come to define Japan’s energy policy, and with potentially grim consequences for its already stalled attempts to reduce CO2 emissions.

It was telling that in the same week as a court blocked the restart of two nuclear reactors on the Japan Sea coast – citing concerns over their vulnerability to a major earthquake – the government released emissions data showing just how far Japan has regressed since the more hopeful days of the Kyoto summit in 1997.

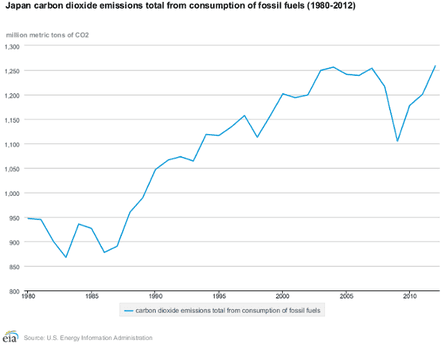

Environment ministry data showed that Japan’s CO2 emissions rose to the second-highest level on record in the year to March 2014.

Local media reports said that Japan, the world’s fifth-largest greenhouse gas emitter, aims to reduce CO2 emissions by about 20% from 2013 levels by 2030 – a much lower target than other major developed economies. In earlier climate talks it pledged a more ambitious reduction of 25% by 2020 from 1990 levels.

The new targets, if as unambitious as reported, are expected to draw criticism when Japan and other G7 countries meet in Germany in June, and at the UN climate conference in Paris in November.

“The Fukushima disaster had a huge impact on Japan’s emissions reduction target, practically and politically,” said Tetsunari Iida, director of the Institute for Sustainable Energy Policies in Tokyo.

As Britain and other countries push for more ambitions reductions, Japan has been accused of reneging on its climate change commitments as it ramps up fossil-fuel use, with plans to build more coal-fired plants in the absence of the nuclear option. All of Japan’s 48 working reactors went offline after Fukushima, and attempts by the pro-nuclear prime minister, Shinzō Abe, to push for restarts risk being held up by months, perhaps years, by legal wrangling.

“The Abe administration is very close to big industry and the power monopolies and they have very low ambitions in terms of climate change policy,” Iida said. “I expect that the new mid-term target, which has to be announced by the time the G7 meets, will be rather low.”

The March 2011 Fukushima disaster shattered the public’s faith in the “safety myth” surrounding nuclear energy, which once accounted for almost 30% of Japan’s energy needs, with plans to raise its share to about half with the construction of more reactors.

Keith Henry, an analyst and founder of Asia Strategy, a government policy consultancy in Tokyo, said sensible discussion of CO2 emissions was being lost amid a highly emotive debate over the future of nuclear power post-Fukushima.

“Depending on which side you believe, nuclear power is the saviour that will return Japan to a stable, secure energy supply and reduce its balance of payments deficit, or will be the potential source of another nuclear meltdown,” Henry said. “The threat of a nuclear meltdown overrides concerns about an increase in CO2 emissions.”

Before an earthquake and tsunami sent three of Fukushima Daiichi’s six reactors into meltdown, nuclear was at the core of Japan’s emissions strategy. But the turning of the popular tide against nuclear has sent policymakers back to the drawing board, and risks leaving Japan’s climate change efforts in tatters.

With all of its reactors idle, Japan has been forced to import record quantities of expensive coal and liquefied natural gas (LNG) that have dramatically increased CO2 emissions and, the business community says, are putting the country’s economic recovery at risk.

Climate change campaigners have accused Abe and his allies of talking up nuclear power to avoid confronting hard choices about its future energy mix. “The government is using this as an opportunity to make excuses not to do more about CO2 reductions,” said Hisayo Takada, climate and energy campaigner at Greenpeace Japan.

“If it did everything possible to tackle climate change, then things would eventually change for the better. But instead, it is hanging on to the old ways of thinking, and barely gives any thought to renewables and energy efficiency.

“Is it right to keep spending money on something that is old and has no future, or to invest in something new and watch it grow? The answer to that is obvious.”

The industry lobby, too, is pushing to switch idled nuclear reactors back on, despite opinion polls showing that most voters oppose restarts. As long as they hold out hope for even a limited role for nuclear, the impetus for serious investment in renewables will be lost, said Aileen Smith of Green Action.

“The utilities are saving grid space for nuclear, which effectively blocks suppliers of renewable energy. In turn, that dampens investment in renewables because investors can’t be sure which way the wind is blowing politically,” said Smith. “It’s clear that far from being good for climate change, nuclear power is actually contributing to higher emissions of global warning gases.”

Paul J Scalise, a senior research fellow at the University of Duisburg-Essen in Germany, said the nuclear shutdown and higher dependence on coal and LNG “doesn’t help Japan’s CO2 targets in any way at all. But you have to bear in mind that climate change is a secondary issue for the power utilities. They want nuclear reactors back online for financial reasons.”

Scalise, an expert on Japanese energy policy, added: “Japan is stuck in a trade-off between economic efficiency and environmental friendliness, and currently there is no political answer to that. In that sense, Japan is right there with everyone else in having this problem.”

Abe’s enthusiasm for reactor restarts is proof that Japan’s “nuclear village” of politicians, utilities and regulators is re-establishing its influence more than four years after Fukushima. But amid public opposition to nuclear restarts and resistance to the extra investment needed to promote renewables, industry’s priority now is ramping up the use of fossil fuels.

“The strongest opposition to a major policy shift towards renewables is coming from industry,” said Mika Ohbayashi, director of the Japan Renewable Energy Foundation in Tokyo. “Since Fukushima, the utilities have faced huge difficulties because they can no longer use nuclear, so that they’re losing an important asset. They want to protect their coal use because in the future, nuclear capacity could fluctuate depending on the political situation.

“They know that Japan won’t be able to switch all of its nuclear reactors back on, and that means coal is their main concern now.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion