Raymond Briggs mourns how his image of a melted snowman turned out, Judith Kerr nixes Michael Rosen’s belief that her tea-drinking tiger was drawn from her subconscious fear of the Gestapo and Quentin Blake provides a new sketch of Charlie Bucket digging into a chunk of vanilla fudge in a unique auction of annotated first editions set to take place next month.

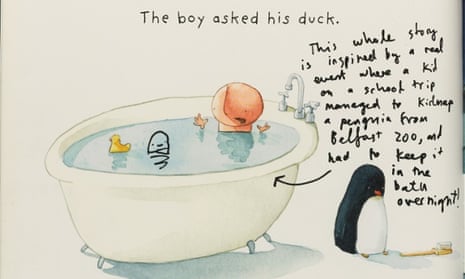

Blake’s charity the House of Illustration, which uses illustration to help develop literacy, creativity and communication, asked the illustrators of 38 modern classics, from Anthony Browne’s Gorilla to Lauren Child’s Charlie and Lola and Helen Oxenbury’s We’re Going on a Bear Hunt, to revisit their most famous works, annotating the children’s stories with drawings, thoughts and memories. Sotheby’s will auction the books on 8 December, with all proceeds to go to the House of Illustration.

Briggs, looking back at his perennial Christmas classic The Snowman, appears to be raising his eyebrows at the boy’s night attire today. “Blue and white striped pyjamas! Pre-historic, I’m told. For me, pyjamas have to be blue and white stripes otherwise they are not pyjamas,” writes the illustrator. And then: “Dressing gown! Pre-historic again? Youngsters now wear ONESIES, whatever they are.”

As the Snowman gazes, entranced, at the television once he has entered the house, Briggs writes: “The Snowman is astounded by the miracle of television, as at one time, long ago, we all were.” He notes, as the character considers the boy’s father’s false teeth: “In the film they made him put the teeth in. I didn’t like that at all,” before going on to reveal his disappointment at the image with which he illustrated the story’s end. “I’ve only recently noticed, after 30 odd years, that the melted snowman almost makes a face – the three lumps of coal resemble eyes and a nose. I wish it wasn’t there.”

Kerr, whose classic picture book The Tiger Who Came to Tea has delighted children ever since it was first published in 1968, notes beside a picture of Sophie embracing the tiger: “The excellent Michael Rosen thinks that I subconsciously based the tiger on my fear of the Gestapo.” Kerr and her family left Berlin in 1933, just before the authorities came to arrest them, going on to write of her experiences in her memoir, When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit. “But I don’t think one would snuggle the Gestapo – even subconsciously,” concludes Kerr.

“The idea behind it is simply for an author or artist to re-engage with their first edition,” said Dr Philip Errington at Sotheby’s. “The act of re-engaging with something which may have gone down as a classic is fascinating, especially because different people have interpreted it in different ways. There are some who have just added an illustration or two, like Quentin Blake, or some, like Judith Kerr and Raymond Briggs, who have gone through and added quite detailed notes.”

Blake’s additions to Charlie and the Chocolate Factory by Roald Dahl include one of the book’s hero, clutching a huge piece of fudge. “This is the only copy of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory with specially added vanilla fudge,” writes Blake. Oxenbury, meanwhile, provides a picture of her bear, hunted by the children throughout Rosen’s story and last seen slinking back to his cave, happily asleep in an armchair. “A day well spent,” she writes.

Bond, looking afresh at A Bear Called Paddington, which was published for the first time in 1958, reveals that “I didn’t sit down to write a book, and paradoxically I think that turned out to be a plus. Because it wasn’t aimed at any particular age group, there is something in it for everyone, and no ‘writing down’ for children – which they hate anyway. So long as the meaning is clear within the text you can go wherever your fancy takes you.”

Paddington, writes Bond, first stemmed from “a small toy bear I had bought my wife. We called it Paddington and I wondered what it would be like for a real bear if it ended up on the station all by itself”. The bear’s famous label, “Please look after this bear”, was “triggered by memories of evacuees arriving in my home town of Reading during the war,” he reveals.

“You very rarely get an insight into how an author or illustrator perceives their own work,” said Errington. “We all know The Tiger Who Came to Tea’s text and illustrations, they’re incredibly famous, but this is an opportunity for Judith Kerr to say ‘this is how I planned to do it’, or ‘this is being read into it, and that wasn’t my intention at all’. I… These will become the ultimate copies – they’re an author’s dialogue with themselves.”

The auction, First Editions: Redrawn, on 8 December will be preceded with an exhibition of the annotated editions at Sotheby’s on the Friday, Sunday and Monday before the sale. The auction house expects the books to fetch up to £10,000 apiece.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion