That the Hillsborough families and survivors finally have some truth and justice is historic; that it took 27 years is a damning indictment of how British society is run. The love, courage and resilience of the relatives – with the help of influential allies such as the Guardian’s David Conn and the criminologist Phil Scraton – eventually overcame powerful elites determined to smear, deflect, disbelieve or ignore them. The South Yorkshire chief constable, David Crompton, has finally been suspended.

But here’s my fear. Yes, there will be a noisy consensus that the unlawful deaths of 96 Liverpool fans was a terrible tragedy, but it will be treated as a throwback to a bygone era: we’ve moved on; lessons have been learned; the families have truth and justice; let prosecutions follow; let no more be said.

That is dangerous. Hillsborough was a story of two things: unaccountable power colliding with “othering”: the stripping away of humanity from a group of people. Both continue to scar our society, and both cause injustice.

A Hillsborough-style tragedy certainly does seem a lot less likely. Health and safety at football stadiums has been dramatically improved, and football has been upgraded to a “respectable” sport (alongside ticket price rises that leave the game unaffordable for too many).

The relationship between government and police has also changed. In the 1980s Margaret Thatcher was confronted with tumultuous industrial unrest, and was determined to permanently break trade union power. One of her first acts as prime minister had been to raise police pay by up to 45%, ensuring their loyalty in the battles ahead.

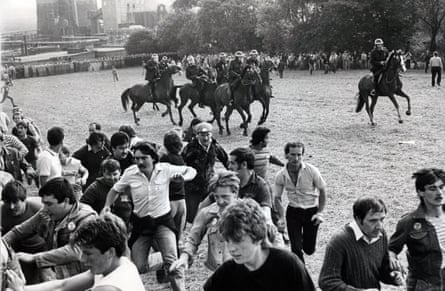

At Orgreave, during the miners’ strike, in what the human rights organisation Liberty described as a “police riot”, there were mass wrongful arrests, for which South Yorkshire police (the same force responsible for the Hillsborough deaths) would later be forced to pay hundreds of thousands of pounds in compensation.

Police statements were allegedly written under direction and altered, the victims were turned into aggressors, and the media echoed the police’s smear campaign. Sound familiar? The striking miners were, said Thatcher, the “enemy within”; Liverpool fans were thugs and scoundrels from a hated city. Hillsborough was the next stop from Orgreave.

Today, with the trade union movement no longer deemed a threat by government, the police are not as indispensable as they once were. The Tories have reduced their number, frozen their pay, and undermined their terms and conditions: basically, what they have done to other workers, but once did not dare when it came to the police. That’s why we’ve ended up with the astonishing sight of Theresa May condemning officers’ behaviour in terms that would have been unthinkable a generation ago.

And yet. Take the “othering”. If officers at Hillsborough had seen their families – or even well-to-do football fans from the home counties – pressed against those fences, their response would undoubtedly have been different. As humans, we have a huge potential capacity for empathy; but when we dehumanise a group of people, we can accept (or indeed inflict) cruelty.

For example, I wonder how different the treatment would have been for Sean Rigg – a black Londoner who died in a Brixton police station in 2008 – if he had been a white Oxbridge graduate like me. His family, including his sister Marcia Rigg, have been forced into a long fight for justice. An initial police version of events was contradicted by CCTV footage. An inquest found that the police had used unsuitable force, contradicting the findings of an earlier investigation by the Independent Police Complaints Commission. Officers were eventually suspended, and five could face charges. But all this took years of struggle.

Similarly, when Ian Tomlinson, a homeless newspaper vendor, died in 2009 after being batoned by a police officer and shoved to the ground at a protest he had nothing to do with, his death could easily have been ignored. Homeless people have a low ranking in the hierarchy of death. Would a well-dressed banker wandering through the protest have suffered the same fate?

The original police version of events – loyally repeated by the London Evening Standard – omitted any mention of police contact, wrongly blaming protestors for obstructing police attempts to help him. Had the Guardian not been passed a video showing what really happened, this version of events would have remained unchallenged.

Protestors themselves are demonised en masse, allowing certain police officers to rationalise inflicting brutality against them. Take William Horner, who had a tooth knocked out during student protests in December 2010. Andrew Ott, the police officer responsible, was convicted of assault four and a half years later only because he didn’t know his comments were being recorded.

“I wanna kill this little lot here,” and “I’ve clouted a few as well, just to get a bit of justice,” he boasted. There is little evidence Ott saw the protestors as fellow human beings. How many other officers thought the same thing, but were savvy enough not to say so on tape?

Sadly, not all injustices have what Horner called “fluke” evidence to overturn them. And that combination of unaccountable power and othering persists, contributing to unavoidable suffering. Miners were violent, militant subversives, Liverpool fans scummy hooligans. Today, whenever I write about refugees I am bombarded with messages describing them all as rapists, criminals, bigots who hurl gay men from rooftops. Such attitudes make it easier for the Conservatives to refuse to take in 3,000 refugee children, even as child abusers and traffickers circle.

“Muslim” has become a synonym for “extremist” and “terrorist sympathiser”. Benefit claimants are widely seen as lazy fraudsters stealing from hard-working Brits. All of these groups lack meaningful power in modern Britain. All, to varying degrees, are robbed of their humanity. They are, quite frankly, seen as having less worth than other human beings. And that, all too often, is a necessary precondition for injustice.

A proper response to the Hillsborough inquest isn’t a complacent sigh of relief, a sense of putting injustice behind us. Instead it must surely mean a renewed determination to challenge unaccountable power and dehumanisation. If we fail to do so, many more families will be forced to spend years of their lives fighting for truth and justice.