On a Sunday morning last September in Waterloo, Iowa, about 150 people filed into the local arts center to hear a speech by the United States' only socialist senator. Vermont's Bernie Sanders, white-haired and 73 years old, spoke for about an hour in his gravelly, thick Brooklyn accent. His views are, he said, "a little different than most views." Sanders denounced the power of the wealthy, advocated for single-payer health care and the public funding of elections — and called for a "political revolution" in America.

The crowd of mostly elderly, liberal Iowans seemed to like the senator's pitch. When Sanders said the top 25 hedge fund managers last year made more money than 425,000 public school teachers, many gasped. When he said Wall Street bankers were "too big to jail," many clapped. And when he opened the floor for questions, one from a younger audience member, Rachel Antonuccio, led to particularly loud cheers. "I have a very simple question," she said to Sanders. "Will you please run for president?"

Once Sanders quieted the applause, he didn't give the standard politician's coy non-response. He admitted that he's "given thought to" running, saying he was motivated by the "enormous problems" the US faces — but he then quickly veered into his misgivings.

"I'm not much into hero worship and all this stuff," he said. "If somebody like me — or me — became president, there is no chance in the world that anything significant could be accomplished without the active, unprecedented support of millions of people, who would be prepared to make a commitment — the likes of which we have not made!"

"60 percent of the American people are not likely to vote in the coming election. You think you can bring around change with that dynamic?"

Sanders argued that his positions — critical of the wealthy and corporate power, supportive of campaign finance reform, skeptical of trade deregulation and cutting social services — had the support of most Americans. But, he said, more than half of the public remained politically apathetic. "Sixty percent of the American people are not likely to vote in the coming election," he said. "You think you can bring around change with that dynamic? You can have the best human being in the world in the White House fighting all the right fights, and he or she will fail."

The question, he said, was whether those average Americans would join the political process — because if they didn't, the power of billionaires and corporate interests would never be checked. He asked, "Will those people stand up and fight?" When someone in the audience yelled out, "Yes," Sanders cut him off. "It's easy to say that they will." He raised his voice further: "But I know that I don't wanna be in the White House taking on the Koch brothers, who'll be running ads 24 hours a day, seven days a week, trying to destroy me and my family and everything else we believe in, and not have people getting involved. And I don't know whether that can happen." He wound down: "That's what I'm trying to figure out."

This week, Sanders confirmed to the Associated Press that he would, in fact, jump into the Democratic nomination race. Most observers, of course, believe that Hillary Clinton is nearly certain to win that contest. Yet over the past several months, progressive activists have grown increasingly unsettled by Clinton's positions on both economic and foreign policy issues. She generally takes a conciliatory, rather than confrontational, tone toward the rich — which is perhaps not surprising, since she's accepted millions in speaking fees and donations from corporations and banks, for both herself and her family's foundation. Like Obama, Clinton wants to win support from, and work closely with, many of the wealthiest people in the country.

Bernie Sanders offers a very different approach. He believes the central issue in America today is that the nation is drifting toward oligarchy. To stop this, he hopes to mobilize the American public — including traditionally Republican constituencies like elderly, rural, and white voters — to back an explicit, full-on challenge to the power of billionaires and corporate interests. With Thomas Piketty's book becoming a best-seller, and politicians like Elizabeth Warren and Bill de Blasio winning enthusiastic support for campaigning on inequality, could the Democratic electorate be ready for Bernie Sanders's pitch?

The socialist senator

The word "socialist" is generally considered an epithet in the US, suggesting support for excessive government power or even Communist-style dictatorial abuse. But it's a term Sanders embraces. A portrait of Eugene Debs, labor organizer and five-time Socialist Party candidate for president, hangs on a wall of Sanders's Senate office in Washington, DC. Back in the late 1970s, Sanders created educational filmstrips for schools, and wrote and narrated one about Debs, in which he called him "a socialist, a revolutionary, and probably the most effective and popular leader that the American working class has ever had." Sanders told C-SPAN in 2011 that Debs pioneered ideas like retirement benefits and a right to health care. When ABC's Jeff Zeleny quizzed him about the socialist label in August, Sanders responded, "Do you hear me cringing? Do you hear me running under the table?"

Debs's portrait is a reminder that over Sanders's four decades in politics — as a perennial third-party candidate, mayor of Burlington, congressman, and then senator — he's been laser-focused on checking the power of the wealthy above all else. Even as a student at the University of Chicago in the 1960s, influenced by the hours he spent in the library stacks reading famous philosophers, he became frustrated with his fellow student activists, who were more interested in race or imperialism than the class struggle. They couldn't see that everything they protested, he later said, was rooted in "an economic system in which the rich controls, to a large degree, the political and economic life of the country."

"Bernie is in many ways a 1930s radical as opposed to a 1960s radical," says professor Garrison Nelson of the University of Vermont. "The 1930s radicals were all about unions, corporations — basically economic issues rather than cultural ones." Richard Sugarman, an old friend who worked closely with Sanders during his early political career, concurs. "We spent much less time on social issues and much more time on economic issues," he told me. "Bernard always began with the question of, 'What is the economic fairness of the situation?'

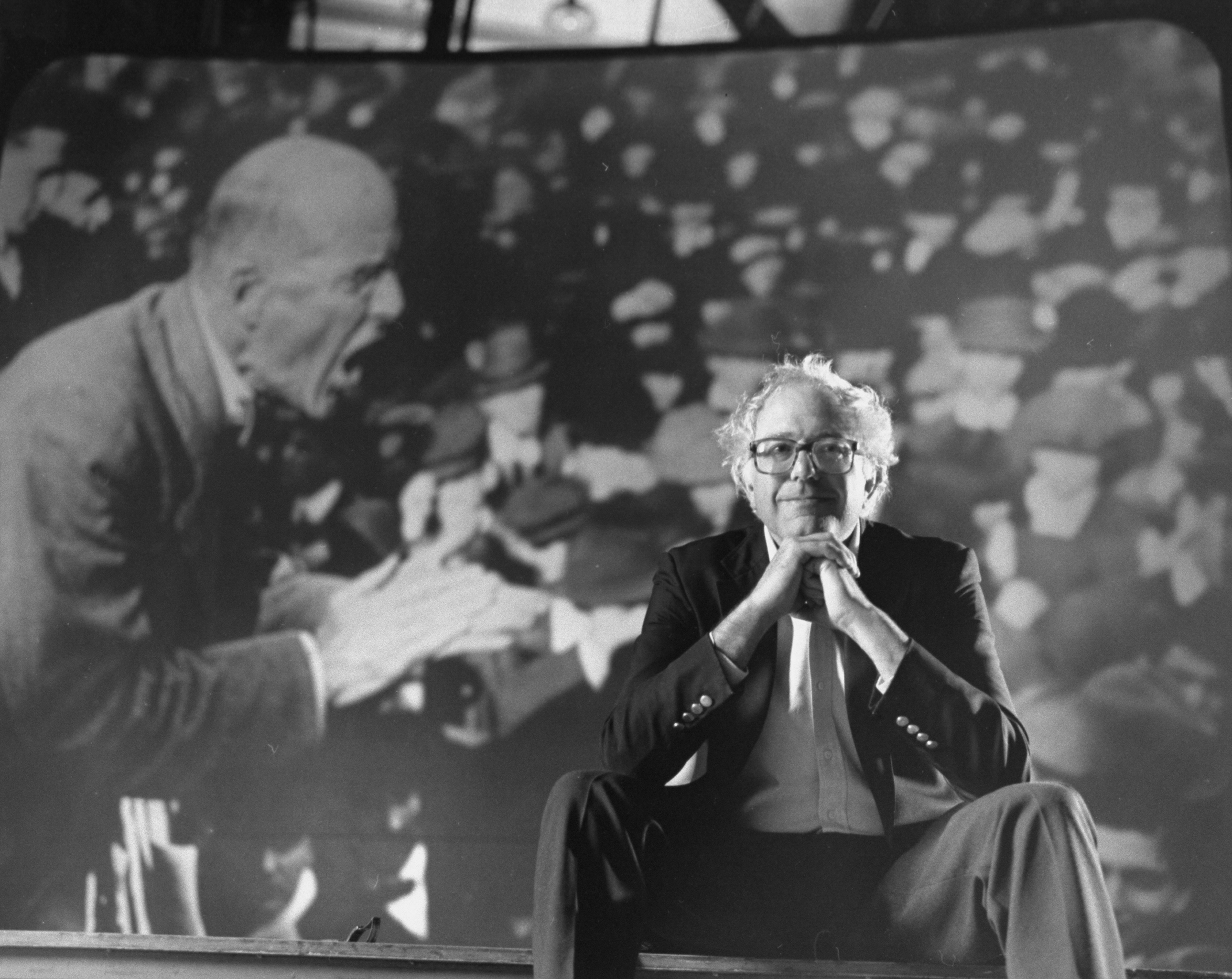

Sanders sits in front of an image of Eugene V. Debs in 1990 (Steve Liss/the LIFE Images Collection/Getty Images)

Sanders's parents were Jewish immigrants from Poland, and his father couldn't speak English. They lived in a small apartment in Brooklyn. "My mother's dream was to own her own home, and she never achieved that," he told me. "We were never hungry by any means. But money was always a major issue within our family. It caused a lot of tension between my mother and my dad."

After college and a few aimless post-graduation years, Sanders moved up to Vermont permanently in 1968, and has lived there ever since. At the time, Vermont was viewed as a rural refuge from New York, and a wave of migrants was reshaping the conservative state. Only a few years later, Sanders walked into a meeting of a local third party, the Liberty Union Party, and walked out its candidate for United States Senate. It would be the first of 20 third-party or independent bids for office — 14 of which he'd win.

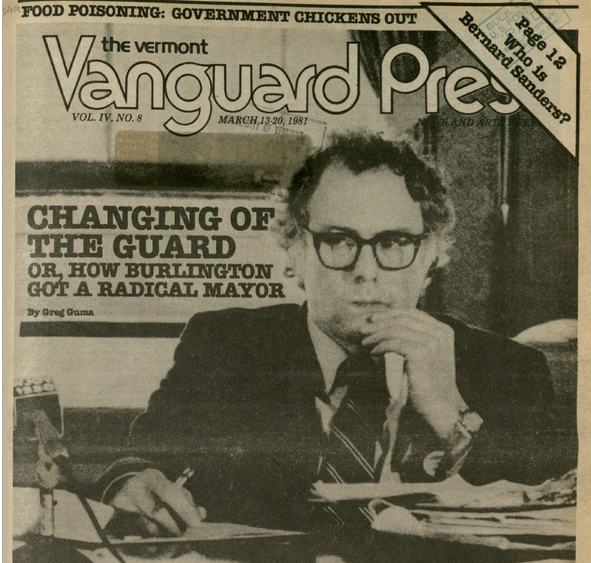

Sanders's first such victory — his election as mayor of Vermont's largest city, Burlington, in 1981 — made national news. Dissatisfied with the rising cost of living, he had come out of nowhere to challenge an entrenched five-term Democratic incumbent, who basically ignored him. But Sanders had a keen political eye for finding defining issues. He opposed a plan to build high-end condos on the Burlington waterfront as a sop to the wealthy, criticized proposed property tax increases as too regressive, and won a crucial endorsement from the city's police union. After a bitter recount battle, he ended up with 4,030 votes to the incumbent's 4,020. Stories across the nation announced that a socialist would become the mayor of Vermont's largest city. One report ran with the headline: "Everyone's scared."

The Sanders agenda

While Sanders is clearly to the left of today's Democratic Party, the platform he laid out in Waterloo, Iowa, was not as extreme as the word "socialist" might lead people to think. "He's a 'small S' socialist," says Nelson. "He's not, 'Let's totally revamp the government, break up the corporations, create five-year plans.' He doesn't get out too far on an ideological limb."

The major issue on which Sanders embraces "full socialism" is health care, where he maintains his longtime support of a single-payer health-care system. In Waterloo, Sanders called Obamacare a "modest step forward," but called for expanding coverage and reducing the costs of care, much as candidates Obama and Clinton did in 2008. The problem is that in the current system, he said, "the goal is for the insurance companies and the drug companies to make as much money as possible." (As a congressman, Sanders brought a busload of breast cancer patients to Canada so they could buy cheaper prescription drugs.)

But support for single-payer isn't so radical in Sanders's home state, which actually started moving toward the nation's first such system in 2011. After years of advocacy, and bitter disappointment at the compromises to the health industry that Bill Clinton and Barack Obama made, Sanders was jubilant over Vermont's achievement. "If we do it and do it well, other states will get in line and follow us," he said. "And we will have a national system." Since then, though, the plan has foundered, with the state postponing implementation indefinitely. "It's not that it hasn't worked out. It hasn't been implemented," Sanders told The Hill in February.

On other issues, Sanders is more like a traditional populist Democrat, willing to disregard the concerns of business and the wealthy in order to try to help the less fortunate. "I voted against all the trade agreements," he told me. "Unfettered free trade has been a disaster for the American people." He has no time for deficit hawks, and instead mocks "entitlement reform" as a "code word" meaning "cutting Social Security and Medicare." Rather than cut Social Security, he says, we should expand it, after raising payroll taxes on the wealthy. On education, he says "it's time we thought about" making college free for everyone. He's argued that the government should spend billions more on infrastructure, to create jobs. And he supports amending the Constitution to allow for greater congressional regulation of campaign finance, like the rest of his party.

Elsewhere, he is more cautious. He has not voiced support for increasing taxes on the middle class, arguing instead that they're already getting squeezed. On social issues, like abortion, gun rights, and gay rights, he is squarely within the mainstream of the Democratic Party — not to its left. And on foreign policy, while he opposed the war in Iraq, he voices sympathy with Israel's security concerns and warns of the dangers of ISIS — positions that have sometimes led to awkward confrontations with a few more radical constituents.

"He knows the game," Nelson says. "Most radicals don't know the game, and they don't want to learn the game because it would compromise their purity. But he likes to win elections, and he has got a very good sense of what will work and what won't." In Waterloo, Sanders voiced confidence that the views he's pushing were broadly popular. "What I believe is on all these issues we have the vast majority of people on our side."

Mayor of Burlington

Half an hour before the Waterloo event, I met up with Sanders at a cafe downtown. It was a chilly, windy Sunday morning, and few places nearby were open. We sat at a table outside, Sanders ordered tea, and I asked him why Obama's presidency fell short of progressives' expectations. "I like Barack Obama. I think he is a very, very smart guy," he said. "His views, his heart, while not terribly progressive, are more progressive than I think some of his actions have shown." But his "major flaw," Sanders said, was his "post-partisan" approach to Washington politics. "He believed that people could sit down in Congress and have serious discussions about serious issues and move forward. Well, he was wrong."

Instead, Sanders said, "there was an unprecedented level of obstructionism" from the GOP, "starting literally from the day he got inaugurated." Sanders argued that the GOP's major strategy was trying to block action on any issue, so the American people would blame Obama for being a failure. "And I think he did not understand that," he said. "That has been their political strategy, and by and large it's been reasonably successful."

If Sanders believes Obama should have been prepared for an immediate, tooth-and-nail fight, perhaps that's because he himself faced one right after being sworn in as mayor of Burlington in 1981. His "most bitter enemies," he told a reporter at the time, were the local Democrats, who controlled the city's 13-member board of aldermen. Board members viewed Sanders's victory as a ludicrous affront, and felt a Democrat was certain to retake the mayoralty two years later. So when the new mayor tried to replace city officials held over from the previous administration with his own appointees, the Democrats blocked nearly all of them, refusing even to hold hearings considering their appointments. Forget socialist reforms — Sanders couldn't even get a staff. "He was operating without any kind of administration," his first mayoral campaign manager, Linda Niedweske, said.

The atmosphere was tense. Early on, his political inexperience was mocked. In one embarrassing case, he nominated a man for a city position without realizing the man had died a month earlier. A Democratic alderman told a reporter that Sanders was "quite crude." A leaflet dubbed the "Burlington Flea Press," written anonymously by an apparent city hall insider, spread rumors that Sanders was truly a communist, not a socialist. He even got a ticket for parking his car in the mayor's parking spot. "I guess now what I expect is that the Democrats on the board are going to attempt to make every day of my life as difficult as possible," Sanders said at the time. "That's fine. We will reciprocate in kind."

A March 1981 cover of the Vermont Vanguard Press is headlined "How Burlington got a radical mayor."

Rather than sway his opponents by reason, or through compromise, he campaigned to get them kicked out of office — recruiting challengers, organizing volunteers, and working himself to exhaustion. Beyond that, he zeroed in on the tedious, day-to-day details of ensuring services were provided. "He understood that if you were going to be mayor of a city with a very cold climate and a lot of snow, that snow removal rather than ideology would most often prevail," says Sugarman. He started to ride around on snow trucks to supervise the plowing, and even started a volunteer program called Operation Snow Shovel to help senior citizens.

The voters rewarded him. In 1982, most of his Democratic opponents went down to defeat, and Sanders's appointees were soon confirmed. And when Sanders himself was up for reelection the following year, he won easily, with 52 percent in a three-way race. "We came close to doubling the voter turnout" compared with his initial election, Sanders told me. "Why? Because we kept our promises. We did pay attention to the low-income and working-class areas. They saw parks being improved, they saw their streets being plowed, and being paved. People saw — 'Oh my god, government works!'"

While some of his most bitter enemies would never fully be won over, tensions with business interests began to cool when they realized Sanders wanted to bring jobs to the city, not confiscate their wealth. "Taxes went up, and the government charged new fees for all kinds of things that kind of aggravated them," Nelson said. "But the smarter businesses learned to live with Bernie." The proposal for making high-rises on the waterfront was killed, but the developer behind it started to work closely with Sanders on other issues, and they became good friends. Sanders's radicalism was mainly limited to foreign policy — yes, Burlington had one, including resolutions supporting the Sandinista regime in Nicaragua. (The mayor's supporters were nicknamed the "Sanders-istas.")

Sanders served four two-year terms as mayor, and left a legacy. "Had Bernie Sanders not become mayor, the city would have become hopelessly yuppified, with poor people being priced out of Burlington," Nelson told the Washington Post's Lois Romano in 1991. Still, nothing like a socialist revolution ever materialized. But Sanders had raised his profile enough to be elected Vermont's sole congressman in 1990 — the first independent elected to the US House of Representatives in 40 years.

Political revolution

Throughout his two and a half decades in Congress, Sanders has often worked with Republicans on individual issues. In 2005, Matt Taibbi dubbed him the House's "amendment king" because, since the GOP takeover of 1994, Sanders had more amendments approved by floor vote than any other lawmaker. "He accomplishes this on the one hand by being relentlessly active, and on the other by using his status as an Independent to form left-right coalitions," Taibbi wrote. Sanders looked for issues that would appeal to most Americans and be broadly popular, even if — especially if — the corporate-influenced leadership of both parties would prefer to avoid them.

But small wins haven't been enough for Sanders, who's always been obsessed with the big picture. He now says the trend he's been warning about for decades — the rise of oligarchy — has only gotten more urgent and dire. Somehow, despite his belief that the American people agree with him, the Republican Party has won many elections, even as it's moved further to the right. "The Republican Party right now in Washington is highly disciplined, very, very well-funded, and adheres to more or less the Koch brother position," Sanders told me. They've "moved from being a right-center party to a right-wing extremist party." As with the Burlington Democrats, Sanders doesn't believe they can be negotiated with on major issues — only defeated.

How would defeat be possible? Democrats already have some advantages among the presidential electorate, with large leads among racial minorities, women, and young voters. But in midterms, the electorate tends to be older and whiter. In 2010 and 2014, Democratic congressional candidates won historically low percentages of the white vote, and in 2012, Obama lost whites and white seniors by the most of any Democratic presidential candidate since the 1980s. Plus the GOP has a built-in edge in both chambers of Congress — from the gerrymandered map and natural geography for House districts, plus the overrepresentation of rural white states in the Senate.

Yet Sanders himself has repeatedly won double-digit statewide victories in Vermont — the second-whitest, second-oldest, and second-most-rural state in the nation. Accordingly, he believes that the only way to break the GOP's power is to turn many of their own core voters — white voters, rural voters, and seniors — against them, and against the power of the wealthy.

This is the political revolution Sanders hopes to achieve, and this is why he's repeatedly visited Iowa and New Hampshire over the past year. "I do not know how you can concede the white working class to the Republican Party, which is working overtime to destroy the working class in America," Sanders told me. "The idea that Democrats are losing among seniors when you have a major Republican effort to destroy Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid is literally beyond my comprehension."

"The agenda of the Koch brothers is to repeal virtually every major piece of legislation over the past 80 years that has protected the middle class"

So why is it happening? "I think the average tea party person is angry because he or she has seen their family's income go down, their college is unaffordable, they're struggling with health care, they've seen their jobs go to China," Sanders said. "But the people who fund the tea party believe in all of those things! So I think the first thing you have to do is explain to them how they are being manipulated by the Koch brothers and the folks who put the money into the tea party."

That explanation has recently been the main theme of Sanders's political project. In Waterloo, Sanders listed a blizzard of statistics about growing inequality — diagnosing the problem. Then, he identified the culprit — billionaires, corporations, and specifically the Koch brothers, whose names he mentioned 18 times. He spent several minutes reading and criticizing the Libertarian Party's political platform from 1980, when David Koch was its vice presidential nominee. He quoted sections supporting "the repeal of federal campaign finance laws," "the abolition of Medicare and Medicaid programs," "the repeal of the fraudulent, bankrupt, and increasingly oppressive Social Security system," and the repeal of minimum wage laws and personal and corporate income taxes.

"The agenda of the Koch brothers," Sanders said, "is to repeal virtually every major piece of legislation that has been signed into law over the past 80 years that has protected the middle class, the elderly, the children, the sick, and the most vulnerable in this country."

Essentially, Sanders is calling for the Democratic Party to wage a rhetorical war on the billionaire class, to better mobilize the general public against them, and break their power. He believes the power of the rich is the defining issue of our politics, and wants to elevate it accordingly. The specifics of how this mobilization happens, and what the public does once it's mobilized (beyond voting out Republicans), are less clear. Sanders's generic suggestion tends to be for a march on Washington. "You wanna lower the cost of college? Then you're gonna have to show up in Washington with a few million of your friends!" he told an audience member in Waterloo. "You wanna raise the minimum wage? Bring 2 million workers to Washington," he continued.

Much of the party has already gravitated toward his rhetoric, if not all of his policies. Last September, every Senate Democrat voted to amend the US Constitution to reverse the Citizens United Supreme Court decision on campaign finance. And Harry Reid has been sounding positively Sanders-esque on the topic of the Koch brothers, mentioning their names on the Senate floor repeatedly in speeches. Though it's just rhetoric, politicians who use it tend to elicit very strong reactions from their targets — Obama's brief, one-time use of the term "fat-cat bankers" resulted in quite a backlash from bankers who felt offended.

Sanders speaks at a 2010 rally in Washington, DC. (Tim Sloan/Getty Images)

But Hillary Clinton is extremely unlikely to take up the banner of class warfare in her presidential campaign. According to a report by Amy Chozick of the New York Times, last September she was exploring, through discussions with donors and friends in business, how her campaign can address inequality "without alienating businesses or castigating the wealthy." And beyond Clinton's desire to raise campaign cash, there's a long-held belief among many Democratic political consultants that messaging critical of the rich simply isn't effective in US politics. Instead, they argue, much of the American public actually rather admires successful businessmen, and aspires to be like them. And lack of trust in government is a real and consistent force in American politics and public opinion.

Sanders acknowledges all this, but wants to persuade people that they should blame the billionaires and corporations pulling the government's strings and gumming up its gears. The problem, he believes, is that many Americans don't believe the Democratic Party will fight for them — because, he says, "corporate influence makes the party more conservative, which raises doubts among people." A campaign focused on issues of inequality and the power of the wealthy, he argued, can convince people Democrats will fight for them again. "You win because you are there fighting for working families all across the board, for seniors, for the children," he says. "That's how you win." Beyond Vermont, though, it's a theory that remains unproven.

A presidential run

After Sanders laid out his misgivings about running for president in Waterloo, an audience member broached the question of whether he might run as an independent or a Democrat. "That's a great question!" Sanders said, animated. "I'd love to get your opinions on it." He laid out his thinking to the crowd. An independent candidacy could be appealing because of "huge frustration at both parties," but it's very difficult to get on the ballot in 50 states. And he emphasized that he would never run as a spoiler if it could lead to the election of a Republican president — "we've made that mistake in the past." On the other hand, if he ran as a Democrat, "it's easier to get on the ballot, you can get into the debates, and the media will take you more seriously." The disadvantage? "People are not overwhelmingly enthusiastic about the Democratic Party."

Sanders asked the crowd which sounded better, and about 80 percent of them raised their hands in favor of a primary contest. "I think you run as a Democrat, because you want to push the debate, with Hillary or whoever it is, in the direction you want to see it go," an audience member said. "We need to hear the establishment challenged." Sanders then asked the crowd another question. "I know Iowa does politics differently than other states," he said, to knowing chuckles. "How many of you would be prepared to work hard if I ran?" A sizable majority raised their hands again.

Now that Sanders is announcing his candidacy, his ideas might get their highest-profile spotlight in decades. In 2007 and 2008, the candidates in the Democratic presidential primary debated 26 times, though that number will surely be much lower this cycle. Sanders's best hope is that few other candidates besides Clinton, or none, enter the race. If there are eight challengers on stage, he could easily be dismissed by the media as a kook, like Dennis Kucinich and Mike Gravel. If it's just him and Clinton debating, that's exactly the contrast he hopes for. "I think there's a hunger for somebody who will take on banks and the corporations and the wealthy," said Huck Gutman, Sanders's former chief of staff.

"How many of you would be prepared to work hard if I ran?" Sanders asked. A sizable majority of the crowd raised their hands.

It's quite plausible that we'll see a moment when Sanders benefits from such a surge of attention, however brief it may be. "I have nightmares that someone like a Bernie Sanders will catch fire and cause trouble for Hillary Clinton," a pro-Clinton Democratic operative told MSNBC's Alex Seitz-Wald last year. But little-known challengers who go up in the polls are then likely to go down. In the GOP race in 2012, dissatisfaction with frontrunner Mitt Romney led to a surge of attention and poll performance for several other challengers — Michele Bachmann, Rick Perry, Herman Cain, Newt Gingrich, Rick Santorum — who soon flamed out. Political scientists John Sides and Lynn Vavreck characterized this pattern as "discovery, scrutiny, and decline." The GOP electorate learned more about an interesting new challenger, but eventually realized he or she wasn't the right choice — perhaps due to concerns over electability.

Still, Iowa and New Hampshire could be two advantageous states for Sanders. Rural and white, they resemble Vermont demographically, and are filled with exactly the sort of voters he wants for his revolution. "A misconception about Vermont is that it's a bunch of Volvo-driving liberals," said Gutman. "A lot more people there drive patched-up old cars than Volvos, and they're the heart of Bernie's constituency. Bernie appeals to working families, seniors, veterans — to people who say 'I'm being pushed and shoved.'" But though outsider Republicans like Pat Buchanan, Mike Huckabee, and Rick Santorum have edged out victories in either Iowa or New Hampshire, true outsider Democrats have had less luck there in recent years. And afterward, the road will only get tougher.

Ideals are nice, but pragmatists deal with the world as it is. Bernie Sanders knows that very well — and so does Hillary Clinton. Even if the political revolution doesn't quite materialize, Sanders, in positioning himself for a run, is reshaping the world Clinton will have to deal with by presenting a threat to her left. How she responds will have implications for her own candidacy, the Democratic Party's platform, and potentially even the presidency. "I like Hillary. I respect Hillary," Sanders told me. "But it is important that we discuss issues. Which is what the future of America will be about."

This piece was originally published in October 2014. It has been updated.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/41762328/91275592__1_.0.0.jpg)