The Wrong Way to Teach Grammar

No more diagramming sentences: Students learn more from simply writing and reading.

A century of research shows that traditional grammar lessons—those hours spent diagramming sentences and memorizing parts of speech—don’t help and may even hinder students’ efforts to become better writers. Yes, they need to learn grammar, but the old-fashioned way does not work.

This finding—confirmed in 1984, 2007, and 2012 through reviews of over 250 studies—is consistent among students of all ages, from elementary school through college. For example, one well-regarded study followed three groups of students from 9th to 11th grade where one group had traditional rule-bound lessons, a second received an alternative approach to grammar instruction, and a third received no grammar lessons at all, just more literature and creative writing. The result: No significant differences among the three groups—except that both grammar groups emerged with a strong antipathy to English.

There is a real cost to ignoring such findings. In my work with adults who dropped out of school before earning a college degree, I have found over and over again that they over-edit themselves from the moment they sit down to write. They report thoughts like “Is this right? Is that right?” and “Oh my god, if I write a contraction, I’m going to flunk.” Focused on being correct, they never give themselves a chance to explore their ideas or ways of expressing those ideas. Significantly, this sometimes-debilitating focus on “the rules” can be found in students who attended elite private institutions as well as those from resource-strapped public schools.

These students are victims of the mistaken belief that grammar lessons must come before writing, rather than grammar being something that is best learned through writing. I saw the high cost of this phenomenon first-hand at the urban community college where I taught writing for eight years, an institution where more than 90 percent of students failed to complete a two-year degree within three years. (The national average is only marginally better at roughly 80 percent.) A primary culprit: the required developmental writing classes that focused on traditional grammar instruction. Again and again, I witnessed aspiration gave way to discouragement. In this seven-college system, some 80 percent of the students test into such classes where they can spend up to a year before being asked to write more than a paragraph. Nationally, over half of university and college students in developmental classes drop out before going any further. Essentially, they leave before having begun college.

Happily, there are solutions. Just as we teach children how to ride bikes by putting them on a bicycle, we need to teach students how to write grammatically by letting them write. Once students get ideas they care about onto the page, they are ready for instruction—including grammar instruction—that will help communicate those ideas. We know that grammar instruction that works includes teaching students strategies for revising and editing, providing targeted lessons on problems that students immediately apply to their own writing, and having students play with sentences like Legos, combining basic sentences into more complex ones. Often, surprisingly little formal grammar instruction is needed. Researcher Marcia Hurlow has shown that many errors “disappear” from student writing when students focus on their ideas and stop “trying to ‘sound correct.’”

There are also less immediately apparent costs to having generations of learners who associate writing only with correctness. Invariably, when people learn that I teach writing, they offer their “grammar confessions.” Sheepishly, they tell me that they “never really learned grammar,” and sadly, it also often comes out that they avoid writing. I have interviewed an executive who locked herself in her office and called her son when she had to write reports, and I have had parents describe writing their child’s paper because the kid was paralyzed with writing anxiety. I have even had people tell me that they passed up job opportunities because they required writing.

Schools that have shifted from traditional “stand-alone” grammar to teaching grammar through writing offer concrete proof that such approaches work. They are moving more students more quickly into college-level courses than previously thought possible. One of these is a program at Arizona State in which students who test below college-level in their writing ability immediately begin writing college essays. More than 88 percent of these students pass freshman English—a pass rate that is higher than that for students who enter the university as college-level writers. At the Community College of Baltimore, a program in which developmental writing students get additional support while taking college-level writing classes has reduced the time these students spend in developmental courses while more than doubling the number who pass freshman composition. More than 60 colleges and universities are now experimenting with programs modeled on this approach.

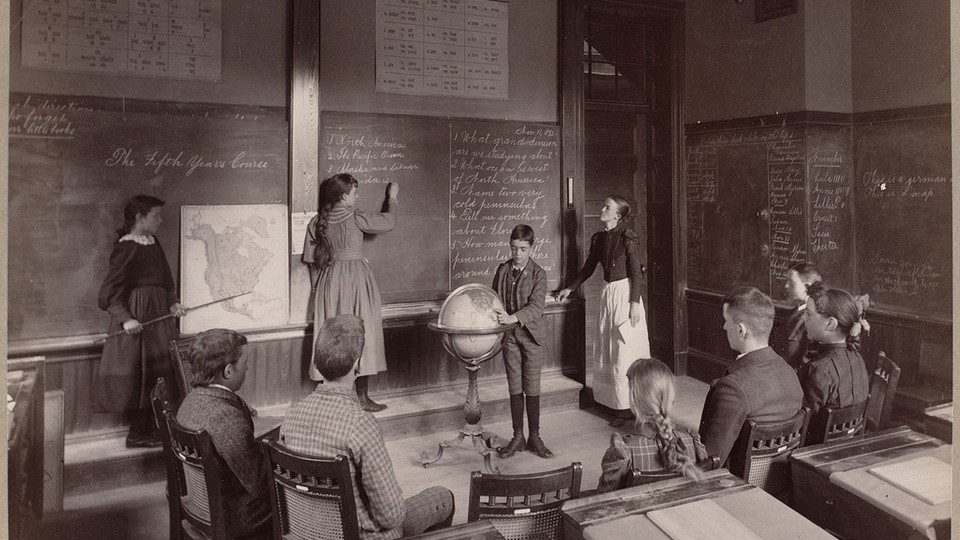

In 1984, George Hillocks, a renowned professor of English and Education at the University of Chicago, published an analysis of the research on teaching writing. He concluded that, “School boards, administrators, and teachers who impose the systematic study of traditional school grammar on their students over lengthy periods of time in the name of teaching writing do them a gross disservice that should not be tolerated by anyone concerned with the effective teaching of good writing.” If 30 years later, you or your child is still being taught grammar independent of actually writing, it is well past time to demand writing instruction that is grounded in research rather than nostalgia.