The Tragic Neglect of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

It leaves people bed-bound and drives some to suicide, but there's little research money devoted to the disease. Now, change is coming, thanks to the patients themselves.

This past July, Brian Vastag, a former science reporter, placed an op-ed with his former employer, the Washington Post. It was an open letter to the National Institutes of Health director Francis Collins, a man Vastag had formerly used as a source on his beat.

“I’ve been felled by the most forlorn of orphan illnesses,” Vastag wrote. “At 43, my productive life may well be over.”

There was no cure for his disease, known by some as chronic fatigue syndrome, Vastag wrote, and little NIH funding available to search for one. Would Collins step up and change that?

“As the leader of our nation’s medical research enterprise, you have a decision to make,” he wrote. “Do you want the NIH to be part of these solutions, or will the nation’s medical research agency continue to be part of the problem?”

For a man who had once churned out breaking news stories in minutes, it had taken four days, with frequent breaks, to compose the 1600-word piece.

Vastag still remembers the exact moment that separates his former life from his new, sick one. In July 2012, he was visiting his family in Wisconsin when a 102-degree fever hit him “like a hammer.”

“Immediately, I felt foggy in the head, like when you have a bad hangover,” he said.

Back in D.C., he took a few sick days, and when the feverishness and dizziness didn’t clear, he pushed himself to work half-time. His primary-care doctor shrugged when he explained his symptoms. He used his connections in the science world to visit the best neurologists in Washington and Baltimore. One doctor performed an MRI that showed damage to his upper spinal cord, but no one could give him a concrete diagnosis. Two months in, his limbs began to twinge with pins and needles, and he wondered if maybe he had multiple sclerosis.

That winter, he lost 30 pounds in two months. He went to a week-long scientific conference for work, and then crashed from the exertion. He would look at his thigh and see the muscles jump, and started thinking that maybe he had Lou Gehrig's disease.

In January, his right arm temporarily became paralyzed and his right eye temporarily went blind. He spent most of 2013 in bed, writing short articles for the Post when he could muster the strength. That summer, he saw a doctor at the National Institutes of Health, who took 29 vials of blood. (The NIH was unable to confirm Vastag’s story, citing patient confidentiality.) Vastag said the results didn’t point to any problem in particular. Frustrated, Vastag told the doctor, “I’m pretty sure I have ME.” (The term most patients, including Vastag, prefer for their disease is “myalgic encephalomyelitis,” or ME. For the sake of clarity and consistency with the existing medical literature, this article uses “chronic fatigue.” More on this naming controversy later.)

“That might be true,” Vastag remembers the doctor saying, “but then the question is, what can be done about it?"

The response encapsulated what Vastag felt was the medical community’s dismissive attitude. The subtext he heard was, “If you have this illness, there’s nothing that can be done about it, so we’re not going to bother with you,” he said.

The experience was just one of the many reasons Vastag has joined a chorus of chronic-fatigue patients who are, gradually and mostly through the Internet, joining forces to draw attention to their plight.

Vastag is working with other patient advocates to try to spur Congress to devote a pot of money—they believe $250 million is realistic—to chronic fatigue syndrome research. Others are running crowdfunding campaigns to fill what they say is a desperate need for funding. Still others are producing documentaries or writing impassioned blogs.

Justin Reilly, a former New York lawyer who also suffers from chronic fatigue syndrome, offered free legal advice for a recent documentary about the disease. He acknowledges it can be hard—and seemingly counterintuitive—for people who are so frail to become activists. But their attitude, he says, is, “I don't want to be like this forever, so I have to summon the energy to do something. Then a little something is done, and we crash.”

When people first get chronic fatigue syndrome, they might think they’re going crazy—some are told as much by doctors. Patients feel ill for weeks and months, bouncing from doctor to doctor and getting diagnosed only through the process of elimination.

Reilly says it feels like, “you wake up one day with a bad flu and it never goes away. Ever.” Sufferers feel achy and weak, with a mental state Reilly describes as trying to think through a “pea-soup fog.” Sleep isn’t refreshing.

Vastag struggles with that same mental torpor, which he occasionally beats back with Adderall, as well as crippling muscle pain, which he relieves with naltrexone, an opiate-addiction drug. Chronic fatigue syndrome’s main dish, a total absence of energy, often comes with eclectic sides, like a rapid heart rate, dips in blood pressure, or unusually cold extremities.

The syndrome is estimated to affect between 836,000 and 2.5 million Americans—the higher figure is about the same number who have schizophrenia—but the majority may be undiagnosed. Fewer than one-third of medical school curricula address the syndrome, according to a February report from the Institute of Medicine. It’s most recognizable by what’s called “post-exertional malaise,” or a worsening of symptoms for days or even weeks after a bout of exercise.

“I can't tell you how astonishing it is to see a previously healthy, 30-year-old athlete short of breath from walking 25 feet,” said David Kaufman, the medical director of the Open Medicine Institute in Mountain View, California. At least a quarter of affected people have been bedridden or housebound. Some 50 to 70 percent are able to remain somewhat functional with the help of different drugs or interventions. The rest keep searching for solutions.

After his experience at the NIH, Vastag headed to New York, where he met with Susan Levine, an internist who is one of the handful of American doctors who specializes in chronic fatigue. After tests showed that Vastag’s body was having trouble fighting viruses that others could easily fend off, Levine started him on an intensive course of antivirals. But according to Vastag, the drugs work best within a few months of the onset of symptoms. He had already been ill for more than a year at that point. The drugs didn’t work.

In February, Vastag took a medical test in which he rode an exercise bike while hooked up to machines that measured how well his body was handling the strain. “Basically, my results were worse than if I was 400 pounds and never got off the couch,” he said. Though he rode the bike for only seven minutes, he felt physically spent for two weeks after the experience.

Like Vastag, many other chronic-fatigue sufferers were once high-functioning, Type-A sorts who were cut down in their prime. The drudgery of fatigue feels even worse when compared to the thrill of an engrossing career.

“I was a science reporter and I’d been doing that for 15 years, and I was good at it, and that got taken away from me,” Vastag said. “It's hard not to have a sense of purpose or identity.”

In the worst cases, sufferers’ symptoms drive them to desperate acts. One woman, a 32-year-old named Vanessa Li, had been sick ever since she took a ski trip in the Italian Alps with her family as a college student and caught a flu from which she never fully recovered. She spent the next 15 years wracked by piercing migraines, chronic pain, breathing issues, and occasional paralysis.

In February, Li died after taking an overdose of sleeping pills. In a note, she wrote that she had been planning her suicide for some time, comparing her choice to the one faced by individuals who dove head-first from the World Trade Center on September 11 rather than burn up in its flames. She donated her tissue samples to chronic-fatigue research.

“For Vanessa, the pain from ME was impossible to describe,” her family wrote in a Facebook post. “She could not go on anymore, not like this without any cure.”

Simple diseases work like a chain of dominoes, with a clear cause setting off a series of possible symptoms, which hint at a diagnosis, and, usually, a standard treatment. Click, click, click, you’re cured. Chronic fatigue is more like a pile of pick-up sticks: a giant mess in which no one can see a beginning or end.

“Most patients begin their history by saying something like, ‘I was totally fine, and I got mono at 19 and I've never been the same since,’” said Kaufman, who later treated Vastag.“I want to find a single, neat, nice packaged cause. Every day I think I’m less and less likely to find that.”

For years, some doctors believed the disease was psychosomatic, and in 1999 the CDC acknowledged that it had diverted millions of research dollars meant for chronic fatigue syndrome to other diseases. Vastag and others believe one culprit for the disease’s shunning might be the “chronic fatigue” moniker. The ailment was originally named “chronic Epstein-Barr virus syndrome,” after the pathogen that was thought to underpin it. But when the causal link between the two wasn’t upheld in studies, researchers writing in the Annals of Internal Medicine in 1988 proposed renaming it to “the chronic fatigue syndrome,” which they felt “more accurately describes this symptom complex as a syndrome of unknown cause characterized primarily by chronic fatigue.” It’s this name that stuck—at least in the U.S.—much to patients’ chagrin.

“Fatigue” makes it sound like an “eye-rolling disease,” as Kaufman puts it. Who hasn’t felt tired or run-down occasionally? Among the more pejorative nicknames that have been lobbed at it are “yuppie flu” and “shirker syndrome.”

“It's literally like calling Alzheimer's ‘Chronic Forgetfulness Syndrome,’” Reilly said. “You'd have people constantly saying to patients, ‘I sometimes forget where my keys are, I think I've got Chronic Forgetfulness Syndrome too.’”

In its report, the Institute of Medicine suggested the illness be renamed “systemic exertion intolerance disease,” after the peculiar tendency of sufferers to get sicker after exercising. One can imagine, though, that name becoming the butt of jokes among couch potatoes who are otherwise healthy, just as “chronic fatigue” has among the mildly sleep-deprived.

The syndrome may be stuck with a vague title until the medical community has a better sense of what causes it. Some studies have since suggested it might be an autoimmune disease, perhaps triggered by an infection and perpetuated by malicious antibodies. Lending support to this theory, a recent drug trial in Norway treated 15 chronic-fatigue patients with a cancer drug that knocked out the B cells that make antibodies, and 10 of the patients got better.

Other doctors think it’s caused by undigested proteins and bacterial debris that seep through the lining of the gut. Or it could be that patients feel ill because of inflammation in the brain; that might explain the disease’s suddenness and its neurological symptoms.

Ron Davis, a professor of biochemistry and genetics at Stanford, began studying chronic fatigue three years ago, after his son, Whitney Dafoe, was stricken with the disorder. Dafoe was in his mid-20s, an accomplished photojournalist and world traveler, when he began experiencing fits of dizziness and abdominal distress. He developed joint pain, which gradually grew so severe he could no longer walk. Now 31, he’s been confined to a bedroom of his parents’ house for the past 18 months. He communicates with them by choosing from a stack of index cards that are pre-written with answers like “yes” and “no.”

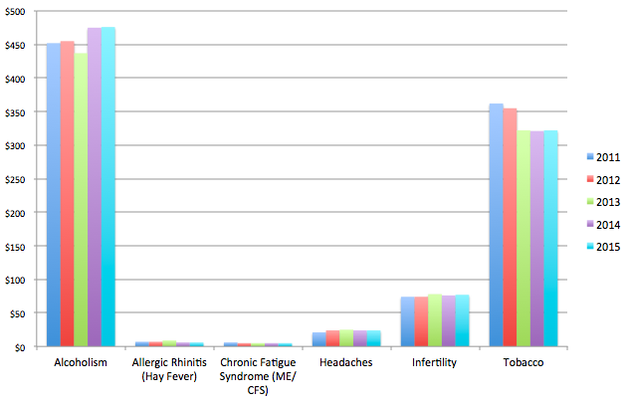

Prompted by his son’s deteriorating state, Davis recently appealed to the NIH for two grants that would total $9 million over five years to study potential biomarkers—microscopic trails the disease leaves in the body. Currently, the NIH devotes $5 million to chronic fatigue syndrome each year. That’s less funding than hay fever, infertility, and headaches—which the agency categorizes separately from migraines.

Davis’s application was denied. “It seemed to me that they simply didn't want to fund it,” Davis said. He thinks there might have been a twinge of bias at play. “One of the problems patients have is that they don't look sick. If they overexert themselves, they look really bad. But you never see them like that because they're in bed.”

Years from now, he says, the medical community will look back on the dearth of research—and the absence of answers for people like his son—and think, “what a stupid tragedy this was.”

The NIH might have other reasons for not supporting research like Davis’s, however. The agency’s funding has not kept pace with inflation, and researchers across disciplines are finding increasingly stiffer competition for grants.

In a statement, an NIH spokesperson said, “NIH funding decisions are based on public health needs, scientific merit, scientific opportunities, portfolio balance, and budgetary considerations, among other factors. Unfortunately, in challenging budget times, NIH turns away many potentially meritorious research applications that cover numerous diseases.”

After two years, Vastag’s illness was starting to make D.C.’s 35-degree winter days feel like they were sub-zero. With his body no longer able to regulate its own temperature, he took to wearing three pairs of socks and thermal underwear whenever he stepped outside, which was rarely. Maybe somewhere warmer and less stressful would bring, if not recovery, at least a nicer sickness, he thought. Through an online support group, he learned of a small community of other chronic-fatigue patients living on the Hawaiian Island of Kauai. A year ago, he packed up his apartment and moved there, too.

Vastag’s medical leave at the Post ran out in January. (“An extraordinarily long period of time for them to wait,” he said, appreciatively.) He’s currently applying for both private and public disability benefits, living on savings and help from his family in the meantime. His disability insurer, Prudential, has been denying his claims, he says, contending that his medical tests don’t prove that he has chronic fatigue syndrome. In a statement, a spokesperson for the insurer said, “Prudential respects the privacy of our policyholders, and, therefore, we do not comment on individual claims. The company's practice is to evaluate all claims in accordance with the terms of the applicable group insurance policy.”

Vastag’s condition hasn’t improved much since his move to Hawaii, but because the weather is nicer, his spirits are a little higher. He sits in his yard and listens to audiobooks—it’s hard to focus on text—and though swimming and hiking are out of the question, he ventures to the beach every once in awhile. Recently, he started dating a woman who also suffers from the disease. “We do nothing together, all the time,” he said.

After his letter was published in the Post, Vastag heard through the grapevine that the NIH was holding meetings about chronic fatigue syndrome—a sign the agency might be taking the disease more seriously. (The NIH did not confirm or deny these meetings, but did say that “there are ongoing internal discussions about recommendations made by the Institute of Medicine report.”)

Meanwhile, in August, the agency awarded a $766,000 grant to the renowned “virus hunter” W. Ian Lipkin, director of the Center for Infection and Immunity at Columbia University. Lipkin is using the money to investigate the role of viruses, bacteria, and fungi in the immune response of chronic-fatigue patients.

Lipkin was helped along by a $220,000 donation from a crowdfund called the Microbe Discovery Project, which had been set up by Vanessa Li before she died. Li launched the effort after having been misdiagnosed by nearly 30 doctors, and she worked on it for over a year with other chronic-fatigue patients around the world.

“Vanessa Li gave us all the push that was needed and made us think about whether we could do it ourselves,” said Amy Williams, a woman who knew Li and also worked on the campaign.

After being turned down by the NIH, Davis is also relying on private donations for his study. With help from the Open Medicine Foundation, he and other researchers from Stanford and Harvard have scraped together $1 million—enough to get started, but not enough for a large sample size or to hire staff. Davis hopes these early experiments might generate enough data to tantalize the NIH grantors later.

The biomarker study is the second chronic-fatigue crowdfunding campaign organized by the Open Medicine Foundation. Though successful, the campaigns have revealed the limits of relying on the kindness of everyday citizens for medical research, where a single study can cost millions of dollars. The foundation was only able to raise the $150,000 it needed for one of the studies because one person donated $125,000.

“Realistically, it's difficult to crowdfund for research from the general, non-patient community,” said Linda Tannenbaum, the director of the Open Medicine Foundation. “When you tell someone you're raising money for [chronic fatigue syndrome], they have no idea what it is.”

That’s why many, including Lipkin and Vastag, believe their best hope still lies in pressuring Congress. Kaufman, who worked with HIV patients before turning to chronic fatigue syndrome, likens the current battle to the one fought by AIDS patients seeking better treatments in the early 1980s.

“I tell my patients, just read the history of HIV advocacy,” he said. “You gotta be in their face to get funding and help. Granted, they were a sicker-looking population. But that's what changed the whole landscape.”