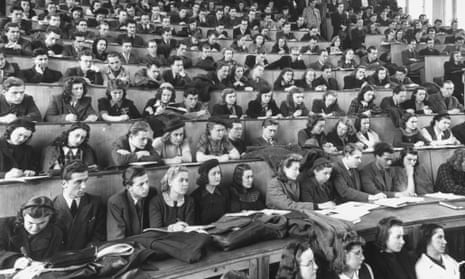

‘It is sad that so few modern students will ever experience a real lecture’

Bruce Charlton, reader in evolutionary psychiatry, Newcastle University, says:

Real lectures are always greatly appreciated by students who want to learn. But what are called “lectures” nowadays are a travesty.

Vast, stuffy venues that seat hundreds; students sitting in the dark and unable to see the speaker; a disembodied voice droning into a microphone; the lecturer reading out endless powerpoint slides which have already been posted online; the scanty audience passive instead of actively making their own notes – distracted by themselves and others intermittently browsing the internet and social networks; and the whole thing being recorded as if to emphasise to students that they don’t really need to be there nor pay attention.

These atrocities are what people currently call lectures, and they are indefensible. But the alternatives to lectures are mere gimmicks and novelties designed to get praise and awards for teaching “innovation”. (A bicycle with triangular wheels is an innovation – the proper question is whether it is fit for purpose.)

When lectures are taken seriously, and conducted in the proper way, they are the best pragmatic way of teaching knowledge to people who want to know.

Good lectures are possible and achievable – I experienced many of them at my medical school. But they are not easy, nor are they as cheap as some alternatives. Good lectures require all-round effort from people who appoint teaching staff and design lecture theatres; from those who construct courses and those who create the educational ethos. And (hardest of all) good lectures require here-and-now concentration during the actual teaching period – effort from both lecturer and audience alike. A good lecture is hard work because it’s a one-off performance. Like the theatre rather than the cinema, everybody present contributes to the success or failure, everybody is involved. But when it works, it’s an experience that may be remembered forever. Real lecturing is irreplaceable in the same way that live theatre or musical performance is irreplaceable – seeing and hearing each other in real-time and working together on something they both value. It is sad that so few modern students will ever experience anything of this kind.

‘There are a myriad of reasons – lapses in concentration or early starts, for example – why students don’t get as much out of lectures’

University teacher Sam Marsh, and senior lecturer Nick Gurski, in the school of mathematics and statistics at the University of Sheffield, say:

Well-delivered lectures can be a good way of passing on knowledge and they dominate teaching in higher education. But there are a myriad of reasons, lapses in concentration or early starts, for example, why students might not get as much from them as we’d hope – and these issues are amplified by large cohorts.

We were faced with stubborn attendance problems on our large first-year modules. Classes often ended the semester half-empty. We’d tried our most popular lecturers, updated the course materials and introduced online tests with little effect. We decided to create a collection of specially-filmed short videos to replace lectures on a module teaching mathematics to engineers.

Students would watch the videos online in their own time and each would be followed by a short quiz. By changing the character of weekly problem classes to include more demonstration and peer discussion we could double their frequency without a big increase in staff time. This would be where students would really benefit from interaction with both lecturers and other students.

When the pilot launched we quickly noticed that not only did students watch the vast majority of the videos on time, but attendance improved dramatically. Over the year students attended three times as many problem classes as traditionally-taught peers from other departments.

When we applied statistical analysis to three years’ worth of exam data, comparing with other cohorts on the same syllabus, we found that we had added somewhere between 4 and 12 marks to the average grade of a student.

Our format is now expanding across the engineering faculty, and next year we will teach 1,000 students in this way.

There may, of course, be a limit to how many videos students can watch in a week. In some cases the time-honoured lecture format is working very nicely. But it seems clear to us that there are lots ways to teach, and some of the best don’t involve lectures.

Join the higher education network for more comment, analysis and job opportunities, direct to your inbox. Follow us on Twitter @gdnhighered.