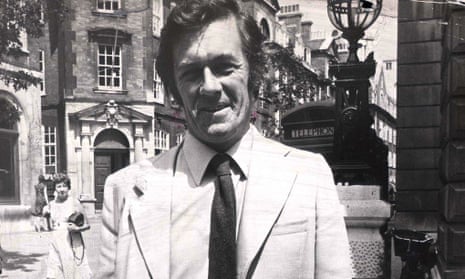

At the end of a Berkshire lane marked “To the Downs” stands a beamed farmhouse, which is the unlikely home of Richard Ingrams, editor of that remnant of Britain’s satire boom in the 60s, the magazine Private Eye.

Last week, he retreated there, among his benign dogs and his horse-riding womenfolk, to ponder the possibility of being forced to close his magazine and go to prison. The criminal libel action contemplated by millionaire financier Jimmy Goldsmith is in gestation. In the words of Mr Goldsmith’s solicitor: “With the searchlights on us we’ve got to get it right.”

Mr Ingrams will be calling on his lawyers to discuss his defence this week. But the business of defending itself against Mr Goldsmith will cost Private Eye a minimum of £30,000 in legal costs. The magazine has always pleaded poverty to discourage litigants. But legal costs of this order would certainly finish it.

The last financial year was the Eye’s best yet. The accounts show a profit of £8,279 before tax, after about £10,000 had been placed towards the libel reserve. In the past, the magazine has maintained its cash flow in the face of legal costs because people who successfully sued were prepared to take their money in instalments.

A special appeal fund has raised £300 (in two days), on top of £6,000 pledged by well-wishers. Apart from Mr Goldsmith’s criminal libel action and his two separate civil actions, the Eye lawyers are dealing with half-a-dozen other actions. Mr Ingrams sees this as the sign of a change of heart towards the magazine on the part of “the establishment”.

“In times of national stress the liberal consensus begins to collapse. People become more settled and cemented in their views and attitudes. It happened to the Week magazine in the 30s. The arrival of the war finished it. There is a closing of the ranks and an unwillingness to tolerate fault-finding.”

There remains the question of whether the magazine has outgrown its usefulness. The gentle ribbing of a ruling class basing itself on the antique values of a bygone age is no longer as relevant as it was.

Other Eye specialities have now become the common currency of journalism, such as showing up the workings of government and the investigation of scandals. Mr Ingrams acknowledges these changes but claims his magazine still has a job to do. “Corruption is the issue today. We are the people to sniff it out.”

He relies on a network of informants. His cosy “Englishness” encourages confidences. It could hardly be disreputable to pass information to a man who plays cricket on a village green surrounded by what Sir John Betjeman once called “the finest plantation of elm trees in England”.

This is an edited extract

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion