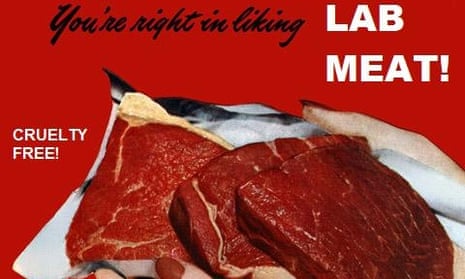

Driverless cars? Half of all Americans would climb aboard. Brain implants? Nearly 30% are open-minded. In-vitro meat grown in a laboratory? Hold the burger.

Only two out of 10 Americans are willing to give lab meat – animal tissue grown without a living host – a go, according to a Pew Research Center poll. A fondness for things high-tech doesn’t transfer easily to the dinner plate, it seems.

Despite this queasiness over heavily modified food (a recent New York Times poll found more than 90% of Americans want GMOs labeled), a new era of so-called “extreme” genetic engineering is already dawning in grocery aisles.

The technology is developing so rapidly that making a distinction between different types of genetically modified foods can be tricky. While genetically modified organisms have had their DNA sequences changed, typically by having traits of another species spliced in with their own, synthetic biology, or simply “synbio,” involves the creation of entirely new organisms with DNA sequences created from whole cloth on a computer. These organisms, typically bacteria or algae, are used to produce valuable commodities such as flavorings and oils.

Research and development on these products is currently kept largely under wraps. Companies are closely guarding the technology – and perhaps the fact that they’re using it at all. Orange and vanilla flavors are currently being marketed and sold, but sellers are not identifying the companies using them and the companies are not identifying themselves.

Though only beginning to enter the market, the general distrust of high-tech foods threatens to bite those companies investing in synbio. Success will require embracing transparency and explaining to consumers the benefits of the new technology.

“There is always anxiety about change,” says Mark Post, who leads a team at the Cultured Beef project at Maastricht University in the Netherlands. “When it’s a more radical change the anxiety is bigger.”

Last year, Post’s group rolled out the first ever lab-produced burger to the public to a predictable flurry of “frankenburger” headlines over the $330,000 five-ounce burger grown from stem cells.

The only way through such bad press, says Post, is openness: “I think it’s important in a high-tech solution to a real-life problem that you are absolutely 100% transparent in what you are doing.”

The problem with secrecy

The importance of transparency is echoed by Andras Forgacs, co-founder and chief executive of Brooklyn-based startup Modern Meadow, which hopes to one day sell in-vitro meat to the public. “We’re asking for a lot of trust from the consumer,” he told the Guardian last month. “The more consumers understand how we do what we do, the better. That includes more transparency and more labeling.”

Synbio was developed largely out of a quest for algae-based biofuels. As that challenge has proven difficult to commercialize for reasons of cost and scale, those same companies are increasingly pivoting to target more immediately lucrative consumer markets.

Fragrances and extracts, as well as soaps and lotions, already contain synthetically derived biological products. Consumers would likely protest if they knew about them, says Dru Oja Jay, a spokesperson for the ETC Group, an international watchdog organization tracking the impact of new technologies on human rights and ecological diversity.

“What we’re talking about here is the wholesale creation of new organisms – and also doing it at the single-cell level that creates a lot of issues when it comes to containment,” Jay says.

It’s not always clear where these products are. Company marketing efforts don’t always help, either.

For many companies, the omission of the term “synthetic biology” from their promotional materials has been an intentional decision due to fears of negative consumer reaction.

But whatever novelty the sector commands is front and center at the website of Ginkgo BioWorks, which bills itself provocatively as “The Organism Company” and whose phone number’s alphanumeric translates as “Hack DNA.” The company boasts that it owns and operates the world’s first “organism engineering foundry”, the products of which endeavor to “replace technology with biology”.

Ginkgo’s website reveals deals for eight chemical fragrances, sweeteners and flavors grown inside yeast cultures. If successful, the shift from biofuel development to the consumer market will mean the company will be able to push beyond biofuel’s $1-per-kilogram value to products valued at as much as $10,000 per kilogram, according to the journal Nature. The company’s customers are not named.

The Swiss biotech company Evolva produces synthetically derived vanillin believed to be entering the food supply, though the end users have not been made public. Future offerings are expected to include synthetically derived saffron, stevia, and resveratrol.

Opening the doors to consumer interest

Green-products company Ecover became the first company to publicly announce its allegiance to an algal oil produced by biotech company Solazyme, a decision that quickly generated a consumer campaign intended to quash the deal. While the campaign calls the oil “synbio-derived”, Solazyme claims that’s untrue because the algae was only genetically modified to increase production of an oil it naturally produces, not to produce chemicals it doesn’t naturally produce.

That hasn’t stopped the petition drive from getting 11,235 signatures. And a harder press by the public would likely follow the release of the company’s two new Solazyme food streams: a “lipid-rich” flour capable, according to the company’s website, of replacing dairy fat, egg yolks, and oil in recipes, and an algae-based “non-allergenic, gluten-free and sustainable source of high-quality protein”.

San Francisco-based Solazyme, manufacturer of Ecover’s new cleaning agent, also sells into Sephora’s beauty line. And Unilever announced in April that it was using Solazyme oils in its popular Lux soaps, skipping any reference to GMOs or synbio.

Interview requests sent to Solazyme and Ecover were not returned by press time.

To gain public acceptance, synbio companies must also sell the benefits of their offerings to a public that is still largely ignorant of the industry’s existence. Three out of four Americans know virtually nothing about the technology, a recent survey found.

“Generally, we find that people tend to be suspicious when you try to refute what they already believe,” says Lars Perner, assistant professor of clinical marketing at the University of Southern California’s Marshall School of Business.

“What tends to be more effective is trying to add beliefs. So you may talk about how you make some of this food affordable. Or you could talk about the convenience.”

Paul Winters, director of communications for the Biotechnology Industry Organization, a trade group supporting the biotech sector, says the industry does a good job on this front. “If you look at the headlines in general for synthetic biology, they are still overwhelmingly positive.”

Unilever and Ecover both say they adopted Solazyme’s oils in an attempt to eliminate their reliance on damaging palm oil. And a protein source such as Solazyme’s might reduce reliance on livestock for meat. While healthy vegetarian diets don’t require any such manipulated foodstuffs, the desire for meat continues to grow despite UN support for vegetarianism.

Alternative protein sources have a strong case to make for themselves, and plenty of novel startups hope to lend a hand.

To bring climate change to heel, global meat production – responsible for as much as 14.5% of global greenhouse emissions, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization – must be dramatically curtailed or significantly transformed.

“You can make [consumers] understand there are problems with meat production the way it’s being practiced now,” Maastricht University’s Post says. “Most people either consciously or subconsciously know they may not know everything about it, and may not want to know all about it.”

The labeling advantage

While Americans are “inclined to let others take the first step” with fast-evolving food technologies, as the Pew Research Center survey found, they generally have a laissez-faire attitude about regulating it – good news for producers of potentially polarizing products.

“The apathy toward things political, including the regulatory, is just rampant,” says Bryan G Norton, professor emeritus at the Georgia Institute of Technology’s school of public policy.

That “laziness doesn’t mean companies shouldn’t label their products, however.

“Providing that opt-out is actually a confidence-building strategy,” says Paul Thompson, who holds the WK Kellogg chair in agricultural, food and community ethics at Michigan University. “It actually is very much in the interests of the industry to accompany [regulation] with options so that people can opt out even if it’s irrational to opt out.”

Rather than earning the public’s trust, disclosure practices like labeling are about not provoking distrust, Thompson says. When choice is stifled, resentment grows, leading in some cases to an “overstatement of risk” by the public in proportion to the sense of powerlessness they feel over their ability to make informed choices.

“From industry’s perspective, it’s not that this will win you trust, friends and warm feelings so much as it’s a defensive strategy that avoids distrust, enemies and overt forms of political opposition,” he says.

Labeling is something company heads have discussed, though it’s by no means universally supported.

“There are some companies and researchers that say synthetic biology should be labeled proudly ‘synthetic biology inside,’ the way you would Intel Inside,” says BIO spokesperson Winters. “Obviously that would be a voluntary label.”

Label or no, all food companies want to avoid getting stuck in the position of having to defend their product’s safety.

A ‘precautionary’ approach

Whatever direction synbio outfits head in their marketing campaigns, a fight is brewing. It’s one that will be shaped by public discourse on food options in light of the ecological pressures brought by world populations and rising affluence.

“That may be sort of a counterbalancing factor here,” says Perner. “People may not be particularly thrilled about these artificial approaches, but the benefits may outweigh the costs.”

In 2012, more than 100 environmental, religious and consumer advocacy groups called for a moratorium on the commercial release of synbio products until regulations guiding the technology are developed.

Last month, representatives of 194 member states making up the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity called for all member nations to take a “precautionary” approach to synbio development and only approve such products for field trials “after appropriate risk assessments have been carried out”.

“There’s going to be a big fight about it, I think,” says Jay. “You’re talking about something that is completely transformative and, to use the business lingo, disruptive.”

Though Norton says the public overwhelmingly favors agriculture of the more traditional variety, exactly where consumers will ultimately draw the line on synbio – already in everything from medicine and fuel to packaging and food – is impossible to forecast.

Caution is the watchword for many.

“It’s very difficult, in light of the way we think about food risks, to stand up and say something is absolutely safe and that there’s no risk,” Thompson says. “Food risk is very complicated. It’s not clear that any of the things we eat or have traditionally eaten are safe. Nor is it clear we ever thought about this very carefully in the past.”

Update: This article was updated after publication to incorporate Solazyme’s response to a request for comment.

The Science Behind Sustainability Solutions blog is funded by the Arizona State University Walton Sustainability Solutions Initiatives. All content is editorially independent except for pieces labelled advertisement feature. Find out more here.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion