Last year was the worst year on record for refugees. The number of people fleeing war and persecution jumped to nearly 60 million, the highest figure since the United Nations' refugee agency began keeping records 50 years ago, and that doesn't even include people driven from their homes by poverty, gang violence or natural disasters.

Smugglers are preying on refugees, social services in poor Middle Eastern and African countries have been stretched to the limit, and Europe and Australia are turning back exiles at their borders. António Guterres, U.N. high commissioner for refugees, acknowledged that relief agencies are overwhelmed. "We don't have the capacity and we don't have the resources to support all the victims of conflict around the world to provide them with the very minimal level of protection and assistance," he told reporters at a mid-June press conference.

By all accounts, it's a mess. But it's likely only a harbinger of things to come if industrialized nations don't dramatically reduce carbon emissions. Drought and desertification already ruin thousands of square miles of productive land annually in China and a number of African countries, while rising sea levels triggered by warmer global temperatures could eventually force tens if not hundreds of millions of people from their coastal homes.

"One of the drivers of displacement and potential conflict over the next 10 to 20 years will be climate [change]-resource scarcity," David Miliband, president of the International Rescue Committee and a former U.K. foreign minister, said recently. "Climate change is going to compound the cocktail that's driving war and displacement."

Global Sea Levels Are Rising Faster

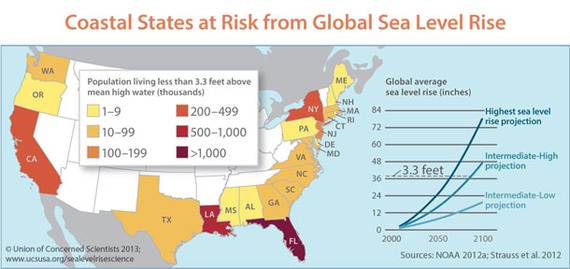

The global average sea level has gone up approximately 8 inches since 1880, but scientists expect it to rise at a much faster rate over the next century. Projections of sea level rise by 2100 range from 1.5 feet to 6.5 feet, depending on how quickly land-based glaciers melt and how quickly industrialized countries rein in carbon emissions.

Based on that range, a 2011 study in the British Royal Society's scientific journal estimated that 72 million to 187 million people would be displaced by 2100 if no action were taken to upgrade coastal defenses. The study projects that small islands and coastal communities in Africa and parts of Asia, which are less likely to have the resources to install costly barriers, are the places most likely to be abandoned.

A 2007 study in Environment and Urbanization, meanwhile, used satellite data to identify coastal areas less than 30 feet above sea level. The study authors then analyzed census figures from 224 countries. Their finding? Some 634 million people inhabit these low-lying areas. That's 10 percent of the world's population crammed into only 2 percent of the world's land mass. Two thirds of the world's largest cities -- those with more than 5 million residents -- are at least partially located there.

The study also found the 10 countries with the largest share of their populations in low-elevation coastal zones are Bangladesh, China, Egypt, Gambia, India, Indonesia, Japan, the Philippines, Thailand and the United States. Climate exile is already a reality in Bangladesh, where millions of people have emigrated northward to escape chronic flooding in the Bay of Bengal's low-lying river deltas. Scientists predict the country will lose 17 percent of its land to rising sea levels by 2050, potentially displacing as many as 20 million people.

Climate exile is also front and center for a number of small island nations, including the Carteret Islands in the South Pacific and the Maldives in the Indian Ocean. The Carteret Islands, a part of Papua New Guinea, began evacuating back in 2009. The Maldives government, meanwhile, is still trying to find a suitable place to move its 380,000 residents before rising sea levels overwhelm its 26 atolls.

Flooding Now the Norm on U.S. East and Gulf Coasts

The United States is bound to have its share of refugees too, given that everybody wants to live near the water. In 2010 more than 123 million people -- 39 percent of the U.S. population -- lived in coastal counties, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. And NOAA expects the U.S. coastal population to jump 8 percent, to 133 million, by 2020.

Sea level rise isn't uniform along coastlines, and over the last century or so a number of East Coast locations have experienced greater-than-average increases. New York City, for example, has seen a 17-inch rise since 1856, while the sea level off Baltimore's coast has gone up 13 inches since 1902. These higher levels have led to regular flooding in cities up and down the coast.

Right now most of that flooding is relatively minor, but scientists say it is going to get a lot worse. An October 2014 Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) report that looked at NOAA tide gauges in 52 municipalities along the East and Gulf coasts found that most could experience three times as many high-tide floods annually in the next 15 years, and 10 times as many in 30 years. By 2045 many coastal communities are expected to see a sea level rise of about a foot. If that happens, a third of the 52 locations in the UCS study -- including Baltimore, Miami and Philadelphia -- would begin to average more than 180 tidal floods a year. Nine cities, including Annapolis, Atlantic City and Washington, D.C., would suffer more than 240 tidal floods annually, some quite damaging.

Alaskans are already facing a much more dire situation. The Arctic is warming at a rate of nearly twice the global average, and over the last 50 years Alaska has warmed 3.4 degrees F, which has thawed permafrost and triggered shore erosion.

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) reported in 2009 that most of the more than 200 native villages in Alaska had been experiencing flooding and erosion due to climate change for some time. Government officials have identified 31 villages that are particularly at risk, and at least eight of them have elected to relocate or explore relocation options, according to the Army Corps of Engineers.

Home to about 350 people, Newtok is furthest along with its relocation efforts. The village, which sits on the Bering Sea coast, found a new site roughly 9 miles away and has obtained some state and federal funds to begin construction there. Even so, cost is a major sticking point. The GAO estimates the price tag for moving the village could run as high as $130 million.

How to Best Protect Coastal Communities

Carbon stays in the atmosphere for decades, so even if every country switched completely to carbon-free energy sources today, sea level rise and tidal flooding would continue to worsen. We can only hope that the world's industrialized nations can reach an agreement on curbing emissions at the upcoming international climate meeting in Paris. Even if they do, nations, states and localities will face a formidable task in protecting their coasts.

A number of U.S. cities and government agencies are taking steps to safeguard communities. Miami Beach and Tybee Island off the coast of Georgia, for example, are upgrading their drainage systems to prevent seawater from backing up and overflowing streets. Norfolk, Virginia, is turning some of its coastal parks into wetlands to buffer storms. And the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, has installed "door dams" to shield building entrances from flooding.

UCS's 2014 report focused on U.S. coasts, but its recommendations for defending coastlines can be applied just about anywhere. They include flood-proofing homes, neighborhoods, and sewer and stormwater systems; curbing development in areas susceptible to tidal flooding; and installing sea walls, natural buffers and other infrastructure. Many of those measures are going to be very expensive, however, so there's no way local communities can go it alone. State, national and even international funding will have to play a major role.

There has been much hand wringing of late about the plight of U.S. infrastructure. Years of neglect have resulted in crumbling roads and bridges, outdated airports, broken water systems, and accident-prone mass transit. Curiously, the debate over this long-festering problem does not include the looming threat of climate change-induced sea level rise. It's a scenario that is playing itself out here and around the world, and some say it will change the face of the planet.

"This will be the largest migration in history," predicts Edward Cameron, a former director of the World Resources Institute's International Climate Initiative who has advised the Maldives. "This is not a migration as we've known it before."

With potentially hundreds of millions of climate refugees seeking safe haven in the decades to come, the time to address this impending crisis is now.

Elliott Negin is a senior writer at the Union of Concerned Scientists.