The Canadian artist Emily Carr grew up on the fringes of the British empire. She was a girl, from a deeply conventional family, thousands of miles from the galleries and museums of Europe and the American east coast, and shackled by the limited expectations and options that women of her class and period faced.

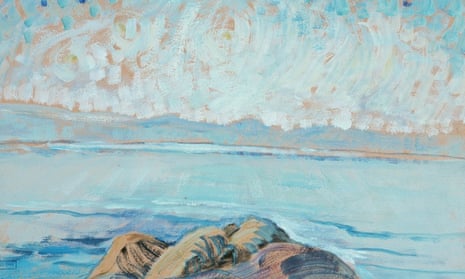

How would she feel about the acclaim with which, seven decades after her death, her work is being greeted, most recently in a new exhibition at the Dulwich Picture Gallery? The inevitable sense of triumph would, I suspect, be tinged with the same emotions that coloured her attitude to the art world and the imperial metropolis: resentment and claustrophobia. Canada’s first true modernist always yearned to return to British Columbia’s rain forests, wild skies and indigenous cultures. “This is my country,” she wrote towards the end of her life. “What I want to express is here and I love it. Amen!” The west coast landscape gave her the subject and spiritual inspiration to create canvases that are dramatic and mysterious.

Carr was born in 1871, the youngest daughter of English immigrants, in Victoria, capital of the newly established Dominion of Canada’s most westerly province, British Columbia. Dominated by British settlers, customs and pretensions, Victoria was possibly the most stuffy and philistine city in North America at the time: children were taught to speak with English accents and parlours were decorated with pictures of Queen Victoria.

Yet even as a child, Carr was fascinated by aspects of her surroundings that most other residents tried to ignore, such as the wilderness that abutted the neat picket fences. This little British settlement was surrounded by untracked rainforest, in which virgin stands of Douglas firs towered in brooding silence. Moreover, across Victoria Harbour there was a group of Coast Salish people who regularly paddled their canoes to the fishing wharves, then went door-to-door, selling hand-woven baskets, fish and berries. They were an exotic contrast to Carr’s family and their bourgeois neighbours.

Emily’s father, Richard, a merchant, recognised her talent when she was eight, and arranged private drawing lessons. She was a headstrong child – an obstinate, square-chinned tomboy who preferred animals to people and fought with her four sisters. As Paula Blanchard, one of her many biographers, wrote: “If she was difficult, as she certainly was, we can applaud her for not allowing Victoria to make her into an anonymous pleasant lady.”

Carr had a passionate response to the world around her: her challenge was to acquire the artistic skills required to capture that response on paper or canvas. British Columbia offered no resources. Both Carr’s parents died when she was in her teens, and there was little money and encouragement from her eldest sister, Edith, now head of the family, to pursue an education at art school abroad. But Carr nagged the family lawyer until he found funds to allow her to study at the California School of Design, in San Francisco. By 1890, Emily had escaped Victoria’s stifling gentility.

During her three years in San Francisco, she received instruction in portraiture and drawing, discovered that she had a good colour sense, and enjoyed weekly outdoor sketching sessions. (She had not entirely shaken off Victoria’s primness: she was too shy to attend life-drawing classes, which featured nude models.)

A few years later, she managed to leave Canada, travel to London and enrol at the Westminster School of Art. The teachers there were dull and old-fashioned (modernism had not yet crossed the channel), and she found urban life – “the breath of monstrous factories, the grime and smut and smell of them” – oppressive. She also took courses at St Ives, in Cornwall, and at Bushey, Hertfordshire, and realised that working alone in the woods was her preferred style. But the tame English countryside was not her landscape. Nor did she find her English fellow students congenial: always sensitive to criticism, she felt despised as a “colonial”. Stress triggered a breakdown; she spent 18 months convalescing in a Suffolk sanatorium.

Carr returned to Canada, and taught in Vancouver for several years. She continued to paint, but was exasperated by her inability to get beyond the conventionally picturesque. In 1907, she did, however, make an important trip with her sister Alice to Alaska. In Sitka, a native village that had been a Russian trading post before it became an American naval station, the Carr sisters discovered extraordinary examples of west coast indigenous carvings, as well as totem poles.

The craft and aesthetic of Sitka’s distinctively non-European culture fired her imagination: she understood its connection to the natural order of which most European settlers were oblivious. “The Indian people and their art touched me deeply … By the time I reached home, my mind was made up. I was going to picture totem poles in their own village settings.” She also hoped that she might finally make some money by selling her reproductions of native art to the new provincial museum in Victoria. But nobody at the museum took her art seriously.

Adventurous North American artists had been flocking to Paris for decades, surfing the successive waves of impressionism, post-impressionism, pointillism, abstraction and fauvism. Carr knew that the most innovative art was happening beyond Canadian borders, and when she saw reproductions of Van Gogh or Matisse, she thought they made “recent conservative painting look flavourless, little, unconvincing”. But she was also nearing 40, she did not speak French and could still only scratch a living from her teaching. How could she get to Paris? And what would Parisians make of this dowdy, reticent, middle‑aged Canadian?

Somehow, Carr scraped together the funds, and in 1910 she crossed the continent and the Atlantic again. Although she fled Paris after only a few weeks (“nearly demented with headaches”), she found a congenial teacher in a dapper, well-connected English artist called Harry Phelan Gibb. Thanks to Gibb, Carr would finally get to grips with the brilliant colours and abstract forms of early 20th-century painting. She recorded how Gibb’s “landscapes and still lifes delighted me – brilliant, luscious, clean”. Only the bulging bodies of his nudes triggered her sense of “revolt”. There was a moment of epiphany one day as she watched him sketch a scene in front of them. “It was not a copy of the woods & fields, it was a realization of them. The colours were not matched. They were mixed with air. You went through space to meet reality.” Concern for detail was replaced by bold brushstrokes and colour on the canvas. Carr went back to Canada determined to apply these lessons to her chosen subject matter.

However, a return to Canada’s west coast also meant a return to geographic and cultural isolation. Not only was she without kindred artistic spirits in British Columbia, she also lacked buyers for her canvases.

For a few years, she struggled on. She made arduous trips through remote native villages, documenting the art of the Haida, Gitxsan and Tsimshian peoples and noting the impact of European immigrants on these once thriving communities. Carr caught the lonely magnificence of indigenous carvings in her paintings such as The Welcome Man and Alert Bay.

In Vancouver she organised a public showing of about 200 paintings completed during the previous 14 years, including Indian pictures and avant-garde canvases from France with their brilliant use of colour. She gave a lecture on her self-appointed mission, explaining that the indigenous artefacts she had recorded “should be to us Canadians what the ancient Briton’s relics are to the English. Only a few more years and they will be gone forever into silent nothingness … ” Her art and her words sprang not from the newcomer’s sense of superiority that characterised so many of her contemporaries, but from the humility she felt before a deep-rooted culture that was rapidly eroding.

Carr’s feelings were not shared by her contemporaries: they did not want “relics” hanging on their nicely painted walls, and the 1913 show was neither the critical nor popular success that the artist had hoped. Carr, always thin-skinned, felt resoundingly rejected.

For the next 15 years, she avoided the easel. She would recall later how she felt only “a dead lump … in my heart where my work had been.” Instead, she earned a living from a diverse range of activities, including running a boarding house, breeding dogs and rabbits and making rugs and pottery. This dogged, passionate, brilliant woman became known as “the crazy old lady” who carried a pet monkey on her shoulder – an image that would endure to this day. Single by choice and fierce in temperament, she resisted most attempts at friendship and would retreat into herself.

Yet the young Dominion of Canada was starting to develop an artistic sensibility of its own. Thousands of miles east, within the more populated province of Ontario, a group of men a generation younger than Carr had banded together to form a Canadian school of art. They canoed the rivers of central Canada and sketched the region’s sparkling blue waters, pink rocks, gnarled trees and brilliant red-and-orange autumn foliage. Then, casting aside the techniques of the old masters, they transformed the sketches into landscape paintings that were characterised by bright colours and a tactile use of paint. They too had absorbed modernist trends from Europe, but unlike Carr, they had no interest in their country’s indigenous inhabitants. The new mythology they were inventing for the Dominion ignored the mythical beliefs of its native peoples.

“The Group of Seven”, as this gang came to be called, after their 1920 show of the same name, was soon acknowledged as the national school. They had done for central Canada what Carr had hoped to do for western Canada: capture the grandeur and immensity of the forests and vastness in a quasi-modernist style. (A selection of their work was shown at Dulwich three years ago.) Their push for a truly Canadian vision, distinct from a European or American style, encouraged Eric Brown, then director of the National Gallery in Ottawa, to look beyond Ontario’s borders to see what was happening elsewhere in the country. In 1927, he included several canvases by Carr in a show of west coast art, and he invited the artist to come east.

This was the trigger for the final, glorious stage of her career. The Group of Seven welcomed her to Toronto. “You are one of us,” declared Lawren Harris, one of the leading figures. She broke through her own shyness to have the discussions she had never previously enjoyed – about technique, aesthetic values, personal style. She returned to her Victoria home, picked up her brushes again, and let rip.

At first, Carr continued to paint the scenes and carvings of the native villages she visited, but in a far bolder style. She focused on the spiritual force that she had always found in nature and that she now recognised was embodied in indigenous carvings. She slowly abandoned the Indian material and turned her attention to the mystery and movement of nature itself. The lush, dank foliage and massive tree trunks of the Pacific rainforest that she painted are quite different from the Group of Seven’s boreal landscapes: as Margaret Atwood remarks, “Her canvases are so green: she takes you right into the middle of the forest.” Carr also commented on the despoliation of environment in canvases of logged hillsides, driftwood or jagged tree stumps. Sarah Milroy, curator of the Dulwich show, points out that Carr always tried to understand “what was being displaced, arguing for its humanity and value, and turning a scathing eye on her fellow colonials, with their superior airs and destructive intrusions”.

Carr’s art continued to evolve as her health failed. Towards the end of her life, she would still insist on stomping off into the woods to paint. She would thin her oils with gasoline, then capture on paper images of trees and skies that pulsate with movement and sensuality. Wordsworthian rapture infuses her vision.

Unlike so much Canadian landscape art, Carr’s work is not a macho story of discovery and conquest, but a haunting and occasionally erotic reminder of mystery. It is also a reflection of a true original. In the words of Marc Mayer, director of Canada’s National Gallery which holds a considerable number of Carrs: “There is a fascinating tension between her urge to record indigenous coastal art and nature, and her determination to make modernist paintings.”

Carr has not suffered the fate of so many women artists. Although the Dulwich show is the first major solo show of her work in Europe, she was recognised as a major artist in Canada several years before her death, aged 74, in 1945. She was also celebrated as an author: Klee Wyck, a memoir of her encounters with different indigenous groups that was published in 1941, won the Governor General’s award for non‑fiction. Her work has never fallen out of fashion. As Mayer says. “She is our Georgia O’Keefe, our Frida Kahlo.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion