It may come as a surprise to learn that we are in the middle of the third great coral bleaching event in human history. And scientists are calling it the severest yet. The last great bleaching event was in 1998 when 11% of the world’s coral reef coverage was lost. Some areas like the Maldives lost as much as 90% of their reefs. This event is worse, possibly much worse. 38% of the planet’s reefs will be affected, with 12,000 sq km of reefs killed off entirely according to experts.

“If things go badly, this is going to be the biggest global biodiversity disaster since the last mass extinction,” says marine ecologist Gregor Hodgson founder of Reef Check, a non-profit organisation that maps reefs around the world and empowers local people to protect them. “Best case scenario, the damage will be extreme – there’s consensus that it will certainly be worse than ’98.”

The culprit is El Niño – a climatic event that occurs periodically and results in warmer ocean waters across widespread locations. While its causes are complex and to an extent unpredictable, its impacts on coral reefs are quite clear: finding themselves literally in hot water, they succumb to bleaching. Microbes known as zooxanthellae, which maintain a symbiotic relationship with coral polyps enabling them to build their carbonate shells start producing harmful free radicals and the corals eject them. If the zooxanthellae don’t return, the corals die.

El Niño events are becoming increasingly destructive thanks in part to background warming from climate change. That’s why this one is set to be the worst on record.

“Right now, Hawaii is experiencing its worst bleaching ever,” says Hodgson. “Several very popular bays are experiencing very severe bleaching – Honolua Bay has been pretty much wiped out. In the Caribbean, corals started dying about three weeks ago and the event is expected to peak in the next couple of weeks.”

The current El Niño has been going on for three years now and with each year, temperatures increase. The National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has now officially confirmed 2015-16 a ‘global coral bleaching event’ having verified its forecasts with data from scientist in the field, including teams from Reef Check, The University of Queensland and XL Catlin Seaview Survey, an organisation that is mapping the world’s reefs using state of the art technology to try and establish much needed baseline data.

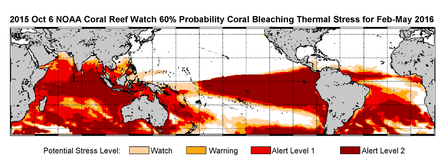

A cursory glance at the NOAA’s Coral Reef Watch long term forecast is alarming – a great swathe of red signifying the highest level of alert in terms of bleaching probability moves across the Pacific towards northwest Australia’s Coral Sea and on into the Coral Triangle, the global epicentre of marine biodiversity, all the way through May 2016.

It’s not just divers or nature lovers that should be concerned. Reefs globally support the livelihoods of half a billion people – 120 million in the Coral Triangle alone. While they cover just 0.1% of the ocean bed, a quarter of all marine species live in them. Behind rainforests, they are the richest ecosystems on the planet.

And like the Earth’s rainforests, reefs are treasure troves whose potential we have barely begun to bring to light, as Hodgson explains. “cytarabine is the most potent drug for treating childhood leukaemia that we know – it was derived from a Caribbean sponge.” In fact it was the first anticancer agent to come from a marine organism. That was just 15 years ago. In another 50, those sponges and a myriad unheralded organisms like them could be gone.

While little can be done to mitigate the effects of this El Niño, Hodgson and his colleagues say it is urgent that we prepare for the next one. They want to explore the possibility of seeding heat resistant zooxanthellae into reefs. According to Hodgson, there needs to be an incentive similar to the X-Prize Foundation’s public competitions, to encourage scientists to come up with innovations that could rescue reefs.

Data gathering is also crucial. Marine organisms are already migrating to cooler waters – tropical triggerfish have been seen in Vancouver. Corals will do the same – their spawn can drift a thousand miles on ocean currents - but they will do it very slowly. “In 1998, Vietnam lost corals 10 metres across and 1000 years old – now what’s the recovery time of a millennium old coral?” Hodgson asks rhetorically.

The UN climate conference in Paris in November and December needs to make coral bleaching and ocean acidification a key priority according to Hodgson. “People are talking about polar bears and I get that, but the second most biodiverse ecosystem on earth is being killed off.

“We shouldn’t just wait for politicians to act. People think climate change is out of their reach, but it really isn’t. Livestock accounts for 18% of greenhouse gases – if every American gave up meat for one day a week, it would be equivalent to taking 7.6m cars off the road.”

The international climate talks are committed to keeping temperatures to 2C, but that won’t be enough to save the world’s reefs. Which makes individual action all the more important.