As the sun shone over London on Friday morning, bringing to an end a week of summer rain, it did not find a city that necessarily shared its cheer.

The previous day, a country which likes to congratulate itself on the reliable autonomy of its elected parliament had entrusted to its people a referendum of shuddering gravitas.

To stay in Europe or not to stay? That was the question. And the answer, while the United Kingdom wiped the sleep from its eyes, was becoming obvious: after more than 40 years as citizens of the European Union, the British people had voted to cut themselves off from the continent.

For all its faults, the EU seemed to be obliging Britain to relinquish, bit by bit, the faded grandeur of its imperial past, and embrace instead the friends on its doorstep.

For all its faults, the EU seemed to be obliging Britain to relinquish, bit by bit, the faded grandeur of its imperial past, and embrace instead the friends on its doorstep.

Whether this counted as the snip of an umbilical cord, or the unshackling of a giant ball and chain depended on your perspective. Either way, the repercussions were swift and unsparing.

The pound went into freefall, suffering its biggest single-day drop in more than 30 years. Prime Minister David Cameron, who had triggered the vote in a bid to address divisions in his own Conservative party, announced he would step down before October. And Europe – including millions of ex-pats who have come to regard the UK as their home – braced itself for… well, no one was really sure.

If this was a brave new dawn, Londoners – the majority of whom had no desire to leave Europe at all – were struggling to locate its sunny uplands.

******

Back in 1944, on the eve of the D-Day landings in Normandy, Winston Churchill is said to have berated the French president, and occasional sparring partner, Charles de Gaulle. “Every time we have to decide between Europe and the open sea,” he complained, “it is always the open sea we shall choose.”

No matter that Churchill, exasperated by de Gaulle’s equivocation over Allied plans, was merely reminding him of Britain’s debt to America. No, in 2016, that was no longer the point of the story. Instead, the anecdote was seized upon by Brexit campaigners as proof that the British psyche has always been Eurosceptic.

The implication hardly needed spelling out. A vote for Leave was a vote for the natural order: just as Britain prefers bangers and mash to frogs’ legs and Sauerkraut, it would rather plump for splendid isolation than muck in with the neighbours.

Watch Video: What’s making news

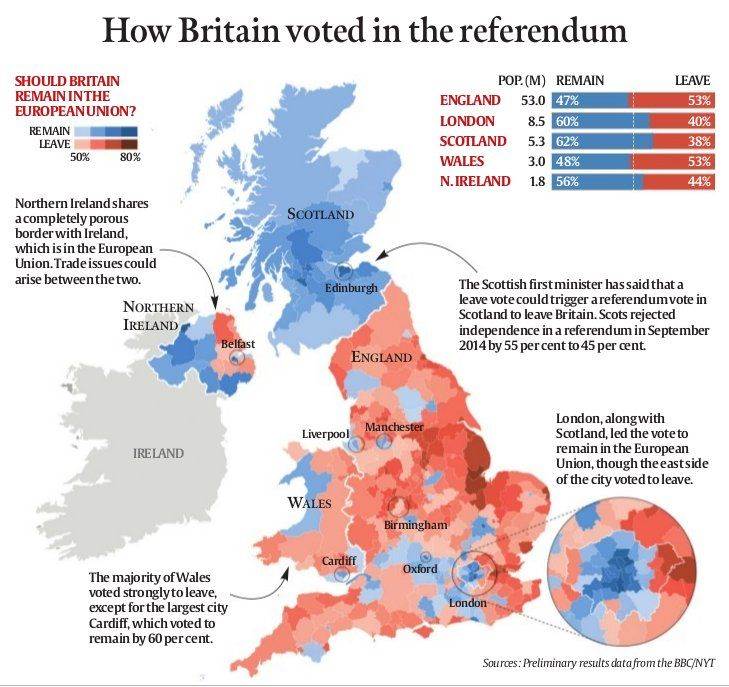

On the face of it, this repeated reference to the cult of Churchill worked rather well. Of the 33.5 million votes cast at the referendum – a turnout of 72%, compared with 66% at the 2015 general election – 17.4 million voted for Leave, and 16.1 million for Remain.

Last-minute polls had suggested a 52-48 split in favour of staying in Europe. In the event, that equation was reversed. Cameron was soon admitting defeat, outside No 10 Downing Street, with dignity and a tremble of the lower lip. Sympathy, though, was limited. This had been a downfall of his own making.

But Britain’s ancient insularity only accounted for part of it. What exactly were the people voting for? And if the UK – to cite another Churchillism – really was “with Europe, but not of it… linked, but not combined”, why did nearly half the electorate want to stay?

Like some rampant tropical garden, this referendum outgrew itself, calling to mind the words of another Conservative prime minister, Harold Macmillan. Asked to name the hardest part of his job, he replied: “Events, dear boy, events.” And, for Cameron, events would take a nasty twist.

He had initially envisaged a solution to Tory infighting: let the people confirm their place in Europe, he reasoned, and the troublesome wing of his party – always agitating for independence – would fall silent. Hell, he might even look statesmanlike while he was at it!

But, in a nation unused to referenda, many sensed a risk. Only two plebiscites had previously involved the entire UK: the 1975 decision (ironically enough) to stay in Europe’s Common Market, and an easily forgotten brouhaha about the voting system in 2011.

Richard Dawkins, the evolutionary biologist better known for his denunciations of God, was no less scathing about the leader of the country. Cameron’s decision to hand the decision to the people was, he wrote, “an act of monstrous irresponsibility”.

As Britons reflected with varying degrees of unease on their new landscape, Dawkins would not have felt inclined to change his view. For one thing, the collapse of the pound now meant France, not the UK, was the world’s fifth-largest economy, which seemed to bear out the warnings among Remain campaigners – warnings dismissed by their opponents as “Project Fear”.

Voters from both camps in London. (Source: Reuters)

Voters from both camps in London. (Source: Reuters)

And, across the Channel, Britain’s former co-members were struggling to take it all in. German parliamentarians were said to be in “shock and disbelief”; the French were deep in crisis talks; and the million Poles who live in Britain, and send home $1bn a year, wondered if they would still be welcome.

Less grandly, a British man who had voted Leave mused aloud on radio about the wisdom of his choice. After weeks of mind-spinning debate, in which personal abuse had supplanted sober analysis, reality was kicking in. No one can say how long the hangover will last.

******

Monstrous or otherwise, Cameron made one fundamental mistake, which alone demanded his resignation. And it was this: he misread the political temperature, both of his own country and of the western world.

Across Churchill’s open sea, the rise of Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders – different sides of the same coin – have fed the American people’s need to raise two fingers to an establishment they sense no longer cares about them. Across Europe, mainstream politicians have taken a buffeting from the far right and the far left.

And so, in the UK, it was the voice of Brexit which positioned itself more effectively, recognising the frustrations of the (mainly white) working-class and urging voters to defy the elite, reclaim Britain’s sovereignty and attend to other grand-sounding projects.

For those watching closely, this was the most exquisite irony in a campaign full of them. After all, leading the charge to escape the clutches of the Brussels elite were Boris Johnson, a former Mayor of London and now a Tory MP with pretensions to replacing Cameron; and Nigel Farage, the leader of the United Kingdom Independence Party, though not — despite several attempts — an elected member of parliament.

Just as Trump has worked his way to the brink of the most powerful job in the world by pretending to speak on behalf of people he would normally cross the street to avoid, so Johnson (educated at Eton and Oxford) and Farage (once a pupil at Dulwich College, one of the country’s swankiest private schools, and a former commodity broker) had somehow convinced Britain’s hoi polloi that they really were with them, not just exploiting them.

And, like Trump, the language they used veered uncomfortably towards demagoguery. Johnson, who had previously espoused views suggesting he would side with Remain, called on his compatriots to prepare for their own “independence day”, an insult to those countries for whom the phrase denotes genuine emancipation, usually from Britain.

Farage, meanwhile, repeatedly told voters to “take back control”. There were plenty of ways of persuading resentful, working-class, white Brits to blame migrants for their woes, and Farage – a master of dog-whistle tactics – invariably found them. One poster depicting a queue thick with Syrian refugees on the Croatia-Slovenia border tastelessly proclaimed “Breaking Point”.

Much of the discourse plumbed depths few thought possible. On the day small flotillas of Leave and Remain boats joined verbal battle on the Thames, one banner summed up the general standard: “Let’s put the Great back into Britain. Vote out and be great again.”

The reason Great precedes Britain, of course, is simply a throwback to the days when “Britannia major” needed to be distinguished from “Britannia minor” (Brittany in France). As so often during this campaign, truth was the first casualty of war.

So too was any sense of national unity. And it was here that London felt more alone than ever. Throughout the capital, Remain beat Leave 60-40; across England as a whole, it was 53-47 in favour of Leave. Scotland and Northern Ireland both voted to stay, and so did small pockets of liberalism, cities such as Oxford, Cambridge and Norwich.

But all this merely exacerbated the sense of them and us – of the university-educated versus the unqualified, of town versus country, of the middle-class versus the working-class, of young versus old.

This last conflict was as telling as any. While 75 per cent of voters aged 18-24 wanted to remain, 61 per cent of those above 65 did not. The baby-boomer generation already had a shaky reputation in the UK, having benefited – to the detriment of younger generations – from a precipitous rise in house prices. Now, it was as if they were deciding on a future that belonged to others.

Many pensioners harked back to the days before 1975, when – in their own minds, at least – England conformed to the nostalgia of poet AE Housman and his “land of lost content”. Never mind the fact that 1974 had begun with a three-day working week imposed by Conservative PM Ted Heath in a bid to save electricity. This was not a campaign overly troubled by facts. Post-truth politics is flourishing on both sides of the Atlantic.

Worse, it was a campaign in which the European Union acted as a whipping-boy for all manner of grievances. One voter told the BBC he was glad he had voted Leave because “at last hardworking Brits can get a pay-rise”. As the respected political commentator Matthew Parris put it ahead of the vote: “Hating the EU has become exciting, brave, a source of self-affirmation, a proxy.”

And there was no denying the hatred. A week before polls opened, Labour MP Jo Cox was murdered outside her constituency office in Yorkshire by a man who later gave his name in court as “Death to traitors, freedom for Britain.” Her death would have been inconceivable in a gentler environment.

In the end, the binary nature of the UK’s choice proved unable to bear the weight of the emotions stirred. And politicians seemed incapable of keeping up.

The Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn, a lukewarm advocate of European integration, all but vanished during the campaign, allowing Brexiters a free crack at engaging traditional Labour supporters in England’s run-down, post-industrial heartlands. For Remain voters, Corbyn’s claim that he had been closer to the public mood than other politicians felt like one last slap in the chops.

And there have been plenty of those over the last few weeks – a time in which Britain has come face to face with some of its basest prejudices, and revealed itself to be a country split in two.

******

The metaphor may yet become tangible, for only a few hours after the last votes had been counted, Nicola Sturgeon, the first minister of Scotland, was telling reporters that a second referendum on Scottish independence from the UK, only two years on from the first, was “highly likely”. At the same time, Northern Ireland’s deputy first minister Martin McGuinness was calling for a vote on a united Ireland. Wales alone voted with England, though it may do them little good.

Other European governments, meanwhile, will inevitably have to deal with cries for their own referenda. The entire project, which began as a response to the Second World War, since when member states have nobly refrained from fighting each other, could now be at risk.

Lovers of historical karma will note that, having patented divide and rule during its imperial phase, Britain has now revisited the policy both on itself and, unwittingly, on the rest of Europe.

For all its faults, the EU seemed to be obliging Britain to relinquish, bit by bit, the faded grandeur of its imperial past, and embrace instead the friends on its doorstep.

Brexit may have imbued some with a renewed sense of importance. It may even have satisfied the need to howl at the establishment and rebuke the bureaucrats. But, though the sun shone over London on Friday, one of the world’s great cities felt diminished – colder and sadder and lonelier than the night before.

Lawrence Booth, who lives in London, is the editor of Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack and a cricket writer for the Daily Mail