Harold Pinter’s obsessive love of cricket has allowed the British Library to date more than 100 letters it has newly acquired, providing fascinating, fresh insights into the young mind of one the greatest playwrights of his generation.

The library announced on Thursday that it was now the proud owner of letters Pinter wrote between 1948 and 1960. But they arrived with a problem: there were no dates.

“It was a nightmare for the curators,” said the library’s chief executive, Roly Keating. “Until they realised almost every one had a reference to cricket and so with the judicious consultation of Wisden and other sources we have been able to put these letters in order.

“They do amount to a gorgeous portrait of the young Harold, which even his biographers have not really had a chance to explore.”

The letters were all written between the ages of 18 and 30 to his lifelong friends Henry Woolf and Mick Goldstein, part of a closely knit “Hackney gang” who knocked around with each other and all went to Hackney Downs school.

It is the playfulness and intimacy in the letters that is particularly striking, said the library’s lead curator of modern literary manuscripts, Rachel Foss.

As well as jokes and girls and laddish nights out, Pinter writes about his frustration at having to earn a living as a jobbing actor - the letters are sent from places such as the Spa theatre, Whitby, and Colchester Repertory Theatre - when all he wanted to really do was write plays.

They also give an insight into the development of what later became one of his most famous plays, The Birthday Party, and he writes at length about his growing interest and admiration for Samuel Beckett.

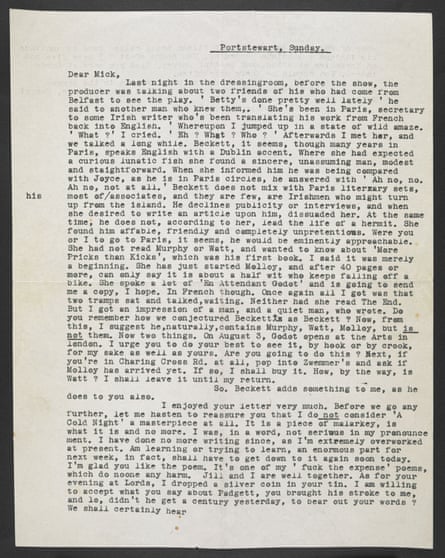

In one, Pinter mentions meeting a woman who worked as Beckett’s secretary in Paris. “Where she had expected a curious fish she found a sincere, unassuming man, modest and straightforward,” writes Pinter. “When she informed him he was being compared with Joyce, as he is in Paris circles, he answered with ‘Ah no, no. Ah no, not at all.’”

Pinter’s intelligence, self-assurance and wit run through the letters. In one he berates the Sunday Times’s critic Harold Hobson for describing Beckett’s novel Watt as wildly comic “and quotes the bit about the pot. All very well, but Watt isn’t as funny as all that, nor is Beckett as funny as all that, without being ‘funny’ he wouldn’t be Beckett, but he is not a ‘humourist’.

“Obviously Hobson has not read The End, nor Malone, nor Malloy. In fact, I don’t even think he’s read Watt either.”

Pinter mentions a performance he gave of Beckett’s novel Malone Dies – under appreciated, he jokes. “Incidentally, you said nothing of my lengthy presentation to you of Malone. You might have done so, in my opinion. Apart from anything else, it took me a fucking long time to type out.”

That humour comes over time and again and there is a lot of intellectual banter. “I read the Gospel of St Mark recently,” Pinter writes in one. “Shocked by Christ’s impetuous treatment of that fig tree.”

But he also makes recommendations to his friends: “A good book is Lord of the Flies by William Golding.”

The library already has Pinter’s archive, which it bought for £1.1m in 2007, but Foss said: “There is very little material from the 1950s so these do shed light on Pinter’s formative years.”

She said it was fun using cricket databases to get the letters in order.

For example in one letter he writes about the young – and, later, great – cricketer Doug Padgett. “Didn’t he get a century yesterday, to bear out your words? We shall certainly hear more of Padgett. And what about Wilson being called back to continue his innings? A unique happening.” The library is certain that the century Pinter refers to is the 115 for Yorkshire against Warwickshire at Edgbaston on 23 July 1955.

One letter reveals Pinter the “cockney lad”. “Last night was a night. I met Barry Foster & Jimmy after work. Your aryan friend was drunker than ever I have seen him. Pissed as ten newts. We schlepped him about, got chucked out of two pubs, he insulted a party of coppers, god save the mark, was nearly run over at every corner, was wearing, in the drizzle & wet of Trafalgar Sq. shirt, ragged trousers & I mean that, holes rather than shoes on his feet and that fucking shapeless hat on his nut, which he all but pissed in.”

The letters have been acquired for £27,500 and will be available to researchers in the library’s reading rooms. One letter will also put on public display in the Sir John Riblat Treasures gallery from 1 December.

Pinter’s widow, Lady Antonia Fraser, said she was “tremendously excited” by the letters: “It was fascinating to hear what a young Harold wrote.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion