When the Supreme Court hears oral arguments in the landmark same-sex marriage case Tuesday, there shouldn’t be much suspense about the outcome. To the extent that one can ever feel confident about predicting the actions of nine very independent-minded justices, we are as certain as can be that same-sex marriage, in one way or another, will get the five votes it needs.

However, just because we think we can guess the outcome, doesn’t mean that Tuesday morning’s session isn’t going to be interesting. Here’s a guide to what to pay attention to in the oral argument.

No. 1: Whether the justices focus more on liberty or equality. There are two basic arguments for marriage equality. The first is that denying same-sex couples the right to marry is unconstitutional because it treats same-sex couples differently than opposite-sex couples; in other words, that the denial violates principles of equality. The second argument is that denying same-sex couples the right to marry infringes on their ability to make personal decisions about important parts of their lives; in other words, that the denial violates principles of liberty.

Throughout the history of same-sex marriage litigation, both arguments have consistently been raised by proponents of same-sex marriage, but the courts have been erratic in choosing between them. Some lower courts have favored the equality framework and others have preferred the liberty analysis.

Supreme Court rulings based on these arguments would have different implications. For instance, a strongly-worded opinion based on equality would affect other aspects of anti-discrimination law, making it harder for the government to justify treating LGBT people differently in public housing, schools, and government services.

A liberty-based opinion, however, would have other effects. If the court decides based on liberty, every state must issue marriage licenses—doing otherwise would violate a fundamental right. An equality ruling would likely also have the same result, but it’s possible a state that wants to prove to the world just how much it really hates gay marriage could get rid of marriage altogether, for everyone, in response to an equality ruling. After all, if no one can get married, then everyone is being treated equally, even if equally terribly. A liberty ruling would prevent this possibility, no matter how far-flung.

A liberty ruling could also have effects that might not have anything to do with the LGBT community at all. For example, if the Supreme Court finds that the right to marry is broad enough to encompass same-sex marriage, other people whose relationships fall outside the typical two-spouse dyad might be able to use the reasoning of this decision in their own quest for government recognition of their relationships. Big Love fans shouldn’t get their hopes up too much, however, because if the court embraces the liberty analysis, it will almost certainly go to great lengths to limit its effects.

When the justices ask questions Tuesday, pay attention to which of these lines predominates. If there’s more intense questioning about one than the other, it may indicate the court is more likely to rule in that direction.

No. 2: Signs that the Supreme Court is going to split the baby. There are two questions before the court. The first is whether all states must allow same-sex couples to marry within their borders, while the second is whether all states must recognize valid same-sex marriages performed elsewhere. If the first question is answered “yes,” then there’s no need for the court to really deal with the second question, because there’s zero likelihood that a state would issue its own licenses but refuse to recognize marriages from other states.

But what if the Supreme Court is just not ready to tell Alabama that it really does have to issue those gay, gay marriage licenses? In that case, the second question becomes critical. Listen to the questions the court asks Mary Bonauto, the lawyer who is addressing the first question. Specifically, listen for questions about why states should have to issue same-sex marriage licenses themselves if the court just makes them recognize marriages that some other state decided to allow. The court may ask her what the real harm would be in that instance—couldn’t you just go to the state next door, get married, and come back? Bonauto has to have a great answer to that question.

If the court seems skeptical of whatever she says, we may be looking at a situation in which some states will issue licenses and others will refuse to issue but must recognize. That’s going to mean a lot of destination weddings.

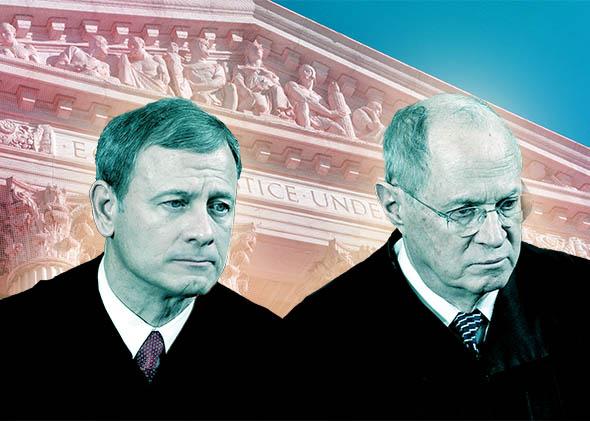

No. 3: Whether the chief justice keeps asking about the “political power” of same-sex couples. Two years ago, when the Supreme Court heard arguments about same-sex marriage but ultimately decided that state bans were not properly before it, Chief Justice John Roberts spent a lot of time at oral argument grilling the lawyer advocating for same-sex marriage about whether gay individuals and couples were politically powerless or not.

This may seem like a weird, maybe even irrelevant line of questioning—but it’s part of an important inquiry in constitutional law. At times in Supreme Court history, part of the analysis of whether a particular group should be protected from bias by the courts has been whether that group is powerless in normal electoral politics. If they are, then it makes sense that the courts need to be more muscular in their protection of that group, and more skeptical of laws that put the group at a disadvantage. That increased level of skepticism is called “heightened scrutiny,” and, so far under Supreme Court rulings, sexual orientation discrimination has not been subjected to heightened scrutiny the way, say, sex discrimination is. But it could be, if the court agrees with some of the lower court decisions on same-sex marriage.

Roberts focused intense attention on this issue in 2013. He seemed pretty convinced that sexual orientation discrimination doesn’t deserve heightened scrutiny because in his view, the gays are doing quite well for themselves politically. He pointed to the changes that have happened in American society with respect to gay rights over the past two decades and speculated that gay people are not a politically powerless group.

Roberts is seen as a possible swing vote in this new case before the court. If he is as committed to this line of inquiry at oral argument this time around as he was last time, it may be a strong signal that he is going to reject the use of heightened scrutiny, and then vote against marriage equality because he believes that gay people should use the political process rather than the courts to accomplish their goals.

No. 4: Whether any justice talks about sex discrimination. As we mentioned, when the government discriminates on the basis of sex, the courts use heightened scrutiny to treat those laws with a bit of skepticism. So far, sexual orientation discrimination doesn’t get that treatment. But what if a same-sex marriage bans actually is sex discrimination? It makes sense when you think about it. When Jim Obergefell sought to marry a man, he received discriminatory treatment—just because he didn’t marry a woman, and because he himself wasn’t a woman.

This argument makes a lot of intuitive sense to a lot of people, but so far, other than a smattering of lower court judges, usually in nonbinding opinions, courts have been reluctant to embrace it. Two years ago, Justice Anthony Kennedy asked a question about it, but he quickly turned to other things.

If you hear a justice start asking about whether the whole thing isn’t just sex discrimination, this may turn into a really interesting opinion indeed. Especially because a decision based on sex discrimination could open up a whole host of anti-discrimination laws originally written to protect against sex discrimination and make these laws protect LGBT people as well.

No. 5: Whether Justice Antonin Scalia cuts off his nose to spite his face. Our favorite arch-nemesis Justice Scalia is in a real bind here. He has spent the better part of the last two decades writing angry, blistering dissents every time the Supreme Court made a ruling that benefits gay people. Usually, the dissent contains dark warnings that the court’s ruling will cause all sorts of horrible things to happen. For instance, masturbation will become legal (it wasn’t?), and of course, that the inescapable outcome will be that same-sex marriage will eventually be legalized.

We know that Scalia will be a vigorous questioner at oral argument, and that he’ll chuck some rhetorical fireballs from the bench that will be quoted in every news report about the case. And we know that it’s a virtual lock that Scalia would rather do pretty much anything other than vote to legalize same-sex marriage nationwide.

But isn’t there a tiny chance that Scalia so badly wants his previous writings to be proven correct that he’s willing to vote in favor of same-sex marriage just to prove that all his predictions of doom and gloom were right all along? We’ll be listening for this, but we won’t be holding our breath.

Read more of Slate’s coverage of gay marriage at the Supreme Court