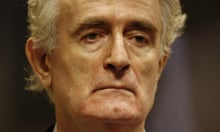

At the end of it all, 21 years since he was first charged, after 11 years on the run, a five-year trial and the 18 months the judges took to deliberate over a verdict, Radovan Karadžić’s moment of judgment came.

The Bosnian Serb leader was convicted of genocide for the 1995 slaughter at Srebrenica, and nine other counts of war crimes and crimes against humanity, including murder, terror and extermination. It was a conviction that ranks as the most serious handed down in Europe since Nuremberg.

The judges at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia were definitive about Karadžić’s key involvement in the Srebrenica massacre, in which more than 7,000 men and boys were rounded up, executed and pushed into mass graves. The presiding ICTY judge delivering the ruling, O-Gon Kwon, said: “Karadžić was in agreement with the plan of the killings”, and had given a coded message to an underling for the doomed Muslim captives, which he referred to as “the goods”, to be moved to a warehouse, from where they were taken out and executed.

During the 100-minute verdict and sentencing, Karadžić sat impassively, dressed in a dark blue suit, not in the dock but on the defence bench, as he opted throughout the five-year trial to act as his own lead counsel. He smiled and nodded to one or two familiar faces from the Serbian press in the gallery, but hardly glanced at the public gallery which was packed with survivors and victims’ family members, mostly women grieving lost sons and husbands. They obeyed the tribunal instructions to stay quiet throughout the proceedings, but there were quiet grunts of disappointment when Karadžić was acquitted of a second charge of genocide for the 1992 killings in Serbian municipalities around Bosnia.

The only time he appeared nervous was when he stood to receive sentence, his arms stiff by his side, but as soon as the judges had gone, he called a huddle of his legal advisers to immediately begin planning his appeal.

“He was surprised at the reasoning that the trial chamber used to convict him, so that was basically the first thing he said: ‘I can’t believe they convicted me like this,’” Peter Robinson, his chief legal adviser, said afterwards.

Karadžić will now have 30 days to file an appeal and it will take three years to hear. The legal marathon will continue and Karadžić will stay in The Hague for the time being. The trial of his military commander, Ratko Mladić, is still under way. The experiment in international justice represented by the ICTY, created in 1993 as an exercise in western penance for failing to stop the killing in Bosnia, will go on for a few more years.

For the survivors and victims’ families packed inside the courtroom, justice was served in a glass half-full. Karadžić was acquitted of a second genocide charge, concerning the massacres that marked the start of the Bosnian war in 1992. The tribunal said it was not beyond a reasonable doubt that he had genocidal intent when those killings took place.

It meant that when the full verdict on all the charges were finally summed up, its first words were “not guilty”. That jarred for many. That and the fact he was given a 40-year sentence, not life. In practice, with time already served deducted, that will mean about 19 years in jail. So it was possible to imagine the 70-year-old former psychiatrist and still aspiring poet emerging alive from incarceration.

“This judgment is a reward for Karadžić. We have no more faith in prosecutors and judges,” complained Hatidza Mehmedovic, a bereaved mother and widow from Srebrenica.

Serge Brammertz, the chief prosecutor since 2007, who kept up the hunt for Karadžić until the fugitive was finally found disguised as a New Age healer in Belgrade, could not hide his frustration that the failure to get a second genocide conviction was being seen as a defeat for the prosecution and an escape for the defendant.

“Sometimes I find it a little bit disappointing that the word genocide is receiving a totally different importance than war crimes and crimes against humanity, where in fact for the individual person ... the suffering for the family is similar, the same,” Brammertz told the Guardian.

That was the law, but not the politics. The term genocide has become politically toxic on all sides of the ethnic divides, which remain as profound as ever more than 20 years after the conflict.

The one thing the former warring nationalist parties could agree on is that they had been unfairly treated by the vagaries of international justice. In Karadžić’s home village of Petnjica, in the Montenegrin mountains, where all the residents share his surname, his cousin Vucko said the verdict “proved we were right to think that the UN court was set up only to punish one people – the Serbs”.

Vucko, his wife, Dusanka, and son, Ranko, huddled to watch the verdict live on television in a small room decorated with Serbian flags, coats of arms, symbols of the Serbian Orthodox church, photos of Radovan and a drawing of a Karadžić family tree. They softly mumbled and grumbled to each other after each charge was read. “What about others? What about those who committed the same crimes against Serbs?” they asked.

Despite the overwhelming evidence presented by the prosecution and accepted by the court, they remained defiant. “There is no justice,” Vucko said.

Nedzad Avdic, in Srebrenica, agreed with the sentiment, but for very different reasons. As a teenager, he had survived a mass execution after the fall of Srebrenica by lying motionless and wounded in a tangle of bodies of his friends and relatives until the killers moved away.

“Honestly, after 20 years it means nothing to me. I read his latest interview on some website, that he gave from prison, and now it seems to me that a bigger punishment would be if he had stayed a fugitive, running away, hiding in forests,” Avdic said by email. “Whatever punishment he gets, there is no punishment severe enough for people like that, given the horrors they put us through. They ruined our lives, us survivors, and as a community we are completely ruined.”

For Avdic, the greater injustice is that the division of Bosnia into two halves, a Muslim-Croat Federation and a Serbian republic, meant the practice of ethnic cleansing had been legitimised.

“Karadžić’s work remains in place here in Srebrenica and there’s no way a judgment can change that. If we look at things now, 20 years later, Karadžić fulfilled his goals, and those that were in his way were killed. The judgment would make sense only if it would somehow address his legacy here in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In any other case, the judgment, for me, is completely pointless.

“I have nothing to lose, I lost so much already, my family is gone, and I have hoped the world would be a bit fairer and a bit less cruel.”

Additional reporting by Ana Bogavac in Petnjica