When an artist with more than 40 top 10 hits to her name finally releases a long-awaited, much-delayed album that contains no obvious singles, what are we to make of it?

On the one hand, you might think – as Rihanna’s Anti plays, and you encounter the Tame Impala cover, and ponder exactly what is going on in the bonus track featuring a lot of Florence Welch and precisely no Rihanna – that this is a bit of a rum old do; a suitably bizarre conclusion to one of the messiest album release campaigns in recent memory. (Of the three singles Rihanna released last year, none appear on Anti.)

Alternatively, as the album’s subtle hooks and smart production bring the picture into focus, you might instead wonder if Anti is the most audacious move yet in the career of a singer whose career is defined by turning left where others turn right.

So has the 21st-century’s ultimate singles act become – someone get Mojo magazine on the phone – an albums act?

To those who have been successful in avoiding the decade-long career of one of the planet’s biggest recording artists, the long and short of the story is this: for more than half a decade, Rihanna released a brand-new studio album every year. In one 12-month period, she released two.

Living her career on fast-forward meant that, within four years, Rihanna had sailed past the point where most artists would have released a greatest hits. But she kept her foot down – in 2011 alone, she had 11 UK hits – and drove her career into the current era where greatest hits albums don’t even exist. This release strategy is most commonly associated, in the modern age at least, with a pop artist terrified of transient fanbases. But Rihanna’s hits continued to be enormous – 2011’s We Found Love was the second-biggest of her career. And there were collaborations, too, with Coldplay, Drake, Eminem, Nicki Minaj and Kanye West.

The music is only half the story, though, because during the past decade, the fame Rihanna enjoyed has shifted, and mushroomed, in both intensity and form.

One of the joys of Rihanna-watching is that, no matter how premeditated certain aspects of her career might be, there is an impulsive, gleeful side that suggests she is actually quite enjoying herself. Like other artists who have appeared in the digital era – Gaga, Katy Perry and Taylor Swift – Rihanna makes everything an event. She knows, for instance, that if she goes on holiday and, while wearing a bikini, bottlefeeds a miniature monkey on a public beach, pictures are likely to surface. Nor will she have been surprised by the avalanche of thinkpieces surrounding last year’s Bitch Better Have My Money video, and she knew exactly what she was doing with Monday’s selfie in which she wore a $9,000 pair of Dolce & Gabbana headphones, captioned “listening to Anti”. That social media post went viral because of the headphones as much as the confirmation that her album was finished. Far from just creating events, it feels as if Rihanna herself is the event.

But then, she is the quintessential modern pop entity. It is significant that Rihanna released her first single within three months of YouTube being invented (her fans are a generation for whom music videos, rather than just songs, are the go-to pop art form), and in the year that MySpace surpassed Google as the US’s most visited website. The timing of her arrival and rise sidestepped the tailing off of the Perez Hilton-type celebrity culture of the mid-2000s and centred on direct-to-fan communication that allowed artists to control their own image. For some acts, this requirement to let the world into their affairs was far from ideal, but nobody on the pop landscape has defined their image as well as Rihanna.

In August 2010, she took control of her Twitter account (“no more corny label tweets”), but it’s through Instagram that she seems to have made most sense of her persona, offering a window into her life that’s convincing, if not totally accurate. In last year’s interview-free Rihanna cover story for The Fader, writer Mary HK Choi noted that while Rihanna seems incredibly “real”, “I can’t picture Rihanna jogging. Or going to the dentist. I usually envision Rihanna in the sun, languidly smoking. In short, I can only imagine things that she’s already shown us.”

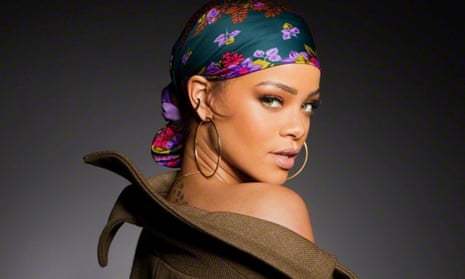

Rihanna’s persona is one that throws up a smokescreen that renders it impossible to deduce whether there is far more, or far less, going on beneath the surface. Regardless, she takes a good photo, operating as a muse to photographers and fashion houses (including Dior, for whom she is currently an ambassador). “There is no one else that excites me more,” noted Alexander Wang in the story accompanying Rihanna’s third Vogue cover. In the same article, Rihanna declares – in a phrase that sums up Anti as much as it describes her penchant for wearing men’s jackets: “You will never be stylish if you don’t take risks.”

Print may be dying, and Rihanna may know that a cover shoot might not sell a single download or prompt one solitary stream, but glossies have the biggest picture budgets. It is complementing attention-grabbing-but-spontaneous Instagram shots with those mega-budget shoots – such as the Harper’s Bazaar shot of Rihanna in a shark’s mouth – that maintains profile. With profile come the big money endorsement deals. Which, in turn, means you don’t have to sell music.

On Thursday, Anti, Rihanna’s first album in more than three years, appeared on the hapless streaming service Tidal (which, you may remember, relaunched in 2015 amid a blitz of publicity with regards to educating the world about the value of music). Then Anti disappeared, because it wasn’t supposed to appear that early. Except fans had downloaded it, and were sharing it online, so then it reappeared. Its price? Free.

Not exactly a home run for anyone attempting to establish the true value of music as an artform, and perhaps not ideal for the album’s numerous co-writers and producers, but win/win everywhere else: Tidal gets customer data and may retain some users (everyone who downloaded Anti was automatically eligible for a two-month trial), while Rihanna, as a Tidal stakeholder, gets a kickback plus the sum she also received from Samsung, with which she embarked on an unexpectedly drawn out ANTIdiaRy pre-release campaign last year.

This might suggest that the quality of Rihanna’s music has become an afterthought, and it would be fair to assume that the critical reception of her work makes little difference to Samsung, or to Puma (whose footwear she has been endorsing in the past 12 months), or to sock company Stance (with whom she has also been working).

Record label logic once ran that fame and celebrity helped to promote music releases. Nowadays, with conventional music revenue collapsing, music is frequently the byproduct of fame and the endorsement deals that come with it. While some artists have taken this as carte blanche to release any old nonsense and put a tour on sale – a rather optimistic, if not short-termist view, of the cycle of celebrity – it is hard not to listen to Anti and deduce that Rihanna has taken a rather more productive view and decided, rather splendidly: I don’t need anybody to buy this. I’m going to do exactly what I want.

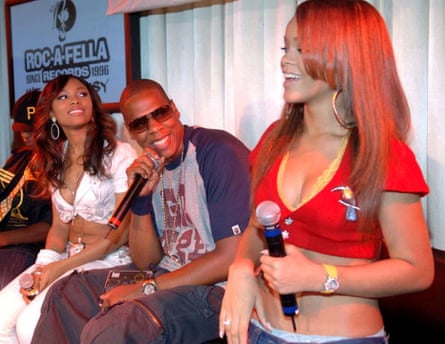

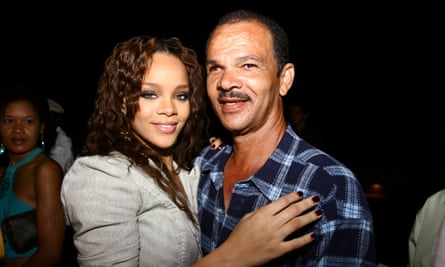

Rihanna’s bolshiness may not have been in evidence when she first met Jay Z, but her star quality certainly didn’t escape her future label boss. She was 16, having grown up 30 metres from the beach in Barbados, amid turbulent family scenes that hinged on her father’s issues with drugs. In her teens, she had formed a girlband with two friends and accosted a producer who was visiting the island on holiday. That producer chose to work only with Rihanna – subsequently stating, as these people often subsequently do: “I always believed she was a star from day one” – which led to an audition with Def Jam. Its president was the first celebrity Rihanna had ever met, but Jay Z was impressed enough by her audition, and concerned enough about the label meetings she had booked elsewhere for later in the day, to demand that the singer stayed with him until contract paperwork had been signed. The story goes that Rihanna eventually left the building at 4am.

Jay Z did have one concern: that Rihanna’s proposed debut single Pon De Replay, which she had performed at her first audition, was so big it would overshadow the young singer. But it became an international hit and, over time, Rihanna would grow into the hugeness of her next singles. At this point she was the classic girl-next-door popstar and her unremarkable debut album was followed just eight months later by A Girl Like Me, an album whose lead single, underpinned by a Soft Cell sample, hinted that there was could be more to this artist than initially met the eye. Her superstar moment came with her third album Good Girl Gone Bad and its lead single Umbrella, which finally propelled Rihanna to the global A-list.

But it wasn’t just the level of success that changed. Her soft image had become more confrontational; Rihanna decided to switch her bouncy hair for a tight, asymmetrical crop. On the album her shift in attitude was painted in broad strokes: thunderous strop anthem Breakin Dishes (“I ain’t demented … well just a lil’ bit”) concerned itself with flinging crockery at a fella’s head, setting fire to his clothes, then burning down his house. There were also tracks such as Question Existing, with swooshy soundscapes, subtle tunes and pensive lyrics, from which it is possible to draw a direct line to Anti. One line in this album’s title track – “easy for a good girl to go bad, and once we gone best believe we’ve gone for ever” – made it clear where Rihanna’s career was heading. Good girl RiRi was gone, but a superstar had arrived.

But it was the following year, and Rihanna’s musical response to the collapse of her relationship with Chris Brown, that defined her as the Rihanna we know today. Rated R was dark, introspective and – compared with the success of its predecessor – a commercial failure. It remains the best album of her career.

After Rated R – and this could be encouraging for anyone nonplussed by the anti-commercial Anti – Rihanna returned to her most straightforward pop. To promote her seventh album, Unapologetic, Rihanna chartered a Boeing 777 and flew selected journalists to seven countries in seven days in what has since been described as more of a hostage situation than a press trip. Though the punishing schedule and disorienting flights didn’t ingratiate Rihanna to many of the invited media personnel, few would again look quite so unkindly on a dazed popstar with little or no idea what city they were in again. They had had a glimpse into the non-stop world of the modern pop entity: a world that was basically hard work.

It wasn’t just a handful of journalists who needed time off after the Unapologetic trip. After seven albums in six years that had also taken in world tours and endless promo, Rihanna stepped off the pop treadmill. At the time, she may not have realised how long she would be gone.

Even before Anti appeared this week, we knew what Rihanna didn’t want the album to be. We knew that she had passed on Major Lazer’s seismic banger Lean On, which last year became the most-streamed song of all time. We also know that Calvin Harris’s submissions were rejected, as was one by Charli XCX, whose Same Old Love ended up in the hands of Selena Gomez.

But there was a sense that she was still struggling. Last summer she talked about her desire for the songs on the album “to make sense together”. She was aware of how impatient fans were becoming, too: “No matter what I post online, within three comments there’s somebody saying, ‘Where is R8’?’ I could post anything. Nothing else matters. They don’t care about anything but that.” But by Christmas, long after she had unveiled the album’s artwork in an LA gallery, and even as the Samsung album teasers were being unveiled, there were rumours that Rihanna was still looking for songs.

Now Anti has arrived, it may prove challenging to fans who say: “Rihanna, I like you for doing what you want, but why won’t you do what I want?” But whatever panic there may have been behind the scenes – it’s impossible to believe that Anti wasn’t supposed to come out before Christmas, or that any of last year’s three singles were really released in the belief that they wouldn’t end up on the album – it works in its final form.

In any case, snatching victory from the jaws of defeat could be the new way forward for pop. Back in 2013, Beyoncé’s album rollout was a fiasco of epic proportions but its surprise release saw it reclassified as a stroke of genius. More recently the Adele album was also plagued by setbacks and jettisoned recording sessions, and that sold reasonably well. As pop trends go, flirting with disaster has got to be more fun than getting things right first time. As Rihanna herself sings on Anti: “Let me cover your shit in glitter, I can make it gold.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion