Embracing the Greatest

In order to honor Muhammad Ali, we must first fully understand who he was.

I do not remember much of Muhammad Ali’s life firsthand. The sharpest memories that come to me are of the middle-aged man, slowed and bowed by a crippling disease, who lit the flame at the ‘96 Olympics in Atlanta. Part of my life has been spent watching Ali’s in reverse; watching his godlike physique and hellfire oratory return, trying to figure out just how the figure of dignified defiance, one whom my elders treated with utmost deference, had been forged.

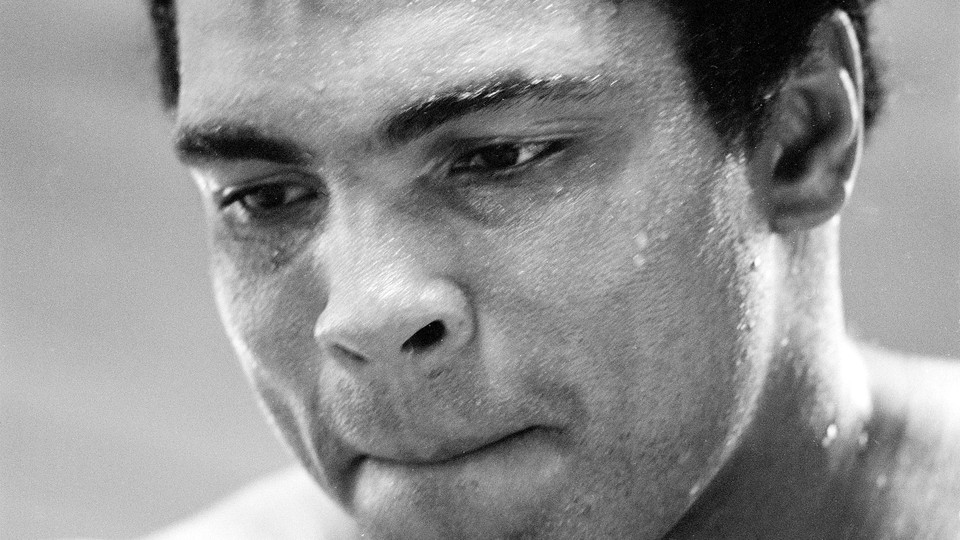

The photograph of his stunning upset knockout of Sonny Liston in 1964––the greatest sports photo of all time––hung over the wall of my uncle’s bedroom. In summers at my grandmother’s house, I would take his poster, taking care to roll it up just right, and pin it to my own bedroom wall with a handful of multicolored tacks. He watched over me in my sleep, and during the day I listened to old records, interviewed family members, and read and watched what I could of the past. My question then was simple, but dictated how and on what terms I came to appreciate him: Who was Muhammad Ali?

Maybe the first answer is that the person we knew as Muhammad Ali was a gestalt of identities. There was the dominating youthful warrior-poet, his most enduring mode, who floated like a butterfly and stung like a bee, and who rumbled until he was no longer a young man. Then there was the leather-tough veteran, a rope-a-doping, slippery, taunting tower of a man. There was the philosopher, the warrior, the conscientious objector, the firebrand, the Black Power icon, and the nonviolent pacifist. There was the man who rejected his “slave name” and scrutinized other black people for not doing the same. There was the elderly man who condemned Donald Trump’s contempt for Islam. There was the patriot, the exile, the Nation of Islam sectist, the Sunni, the father, the brother, the husband, and the ex-husband. There was Cassius Clay, Baptist chrysalis, and then Muhammad Ali, Muslim man. He contained multitudes.

Each of those identities was welded together, though, by Ali’s enduring love for and contemplation of blackness. Ali’s idea of blackness––not merely a skin color or ancestry, but a resistance to white supremacy itself––without an iota of apology was part of his beauty, as George Foreman’s heartbreaking Twitter memorial remembers. But it was also existentially dangerous. There were death threats and jeers. After Ali was made eligible for the draft in 1966, he was convicted and sentenced to prison for his refusal on religious and racial grounds. He was stripped of his boxing license and his passport and essentially exiled for his resistance. His response was defiant. “They never called me nigger, they never lynched me, they didn't put no dogs on me, they didn't rob me of my nationality, rape and kill my mother and father,” Ali said of the Vietcong. “Shoot them for what? How can I shoot them poor people?”

Ali was one of the greatest boxers of all time, no doubt, but I’ve found his true skill to be his role as a public intellectual, expressing his unapologetic blackness in the face of life-threatening danger. He bridged the old gap between disparate branches of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement, embracing Malcolm’s religion while veering closer to King’s vocal anti-war nonviolence. He was a face of the Black Power movement and inspired organizations such as the Black Panthers and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. Perhaps more than anyone, Muhammad Ali provided the public voice for a race seeking to move forward in movement after losing King in 1968.

That voice reverberates today. Even in death, Muhammad Ali is everywhere. He is in Mike Tyson’s fast-talking menace. He is in Michael Jordan’s singular greatness and arrogance. He is in Russell Westbrook’s scowl, Steph Curry’s public religiosity, and Cam Newton’s smile. He is in Serena Williams’s dominance. He is in President Obama’s swagger. He is in hip-hop; his quotes have been pretty much the bedrock for the art’s boasts of masculinity. His anti-war stance, racial philosophy, and confrontation as praxis are directly evident in black millennial protest today. Fanciful a thought as it may be, I like to envision that some of him speaks through me as well.

Understanding Ali is vital in figuring out how to honor him. He was a man who stood against a racist and militarist state. It is not possible for warmongers to celebrate him in good faith, nor it is possible for a man who threatens to ban Muslims from entering the country to do so. It is not possible for people who condemn Serena Williams for arrogance to fairly eulogize Ali. It is not possible for those who are “colorblind” or see blackness as a thing to be “transcended” to truly see a man who saw his blackness as a central and enduring part of his identity. And it is not possible for those turn a blind eye to America’s white supremacist sins to truly ponder the greatness of the Greatest.

To embrace Muhammad Ali is to embrace a radical, a man of contradictions and convictions who would still not be looked on kindly today if his rise and rhetoric were repeated. It is to grapple with arrogance as a therapy; with resistance as a default mode. Embracing him is embracing his multitudes.